How Roku Grows: The Platform For Streaming Platforms

What we can learn about Trojan horses, popcorn strategy, thinking in layers, and the power of defaults

👋 Welcome to How They Grow, my newsletter’s main series. Bringing you in-depth analyses on the growth of popular companies, including their early strategies, current tactics, and actionable business-building lessons we can learn from them.

Hi, friends 👋

Today we’re digging into a company that wasn’t on my radar for a deep dive at all. But, after my post on Why Quibi Died, a reader suggested I look into a product you may well be aware of: Roku. ROKU 0.00%↑

I’d never really used Roku, wasn’t too familiar with their business model, and honestly was skeptical this would be a strong candidate for a deep dive.

But oh, was I wrong.

If you’re not familiar with what Roku is, let’s start with this bold statement: They are probably one of the most important companies in the media and entertainment industry. Or more specifically, the over-the-top (OTT) market, which provides TV, film, and other digital content directly to the user, on-demand, over the Internet. And as cord-cutting of cable and satellite increases, Roku continues to become more significant.

You’ve heard it before…the cliche “streaming wars” rage on as much as ever, with pretty much every major media company having added their own streaming platforms to the mix. Competition is deep, we’re all overwhelmed with choices, and we’re consuming more content than ever.

Today, 78% of households in the US subscribe to at least one streaming service (I have ~10) and are watching over 15 million years’ worth of content every year. That’s 40,000 years a day. 😵💫

But, while all the big names like Netflix, HBO, Disney, Hulu, and Peacock have a turf war for subscribers and fight to win the biggest share of those streaming hours…Roku isn’t too worried.

Why?

Because they are the turf.

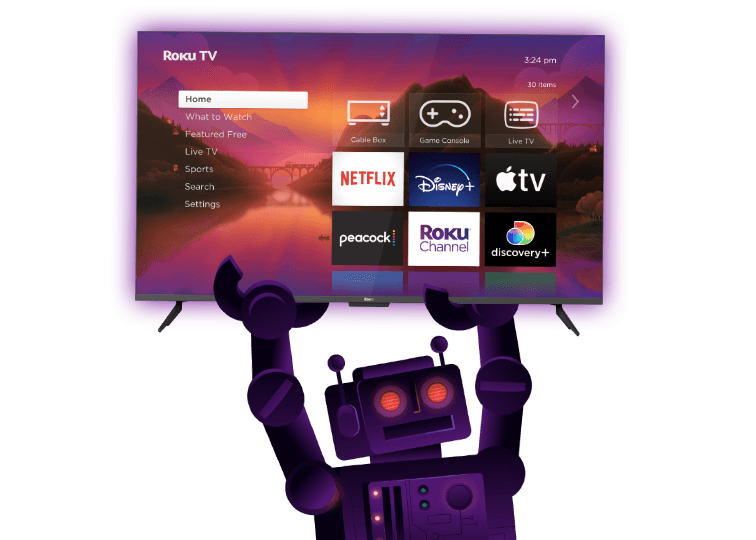

What Apple’s App Store is for apps, Roku is for streaming services.

To put it less metaphorically: Roku is the platform (and aggregator) where over 30% of American consumers find channels/services and stream content every day. Through their brilliant hardware and software play, Roku has created a killer combination, positioning them as the operating system for the modern TV and media ecosystem. They’re the gatekeepers for content discovery and consumption where consumers are spending the most time watching it—the TV.

And, by becoming the platform of platforms with over 120M users in the US, Roku has built one of the strongest ecosystems in the game — collecting all sorts of rental fees for the massive amount of economic value moving through the Roku-verse.

Folks, there are a ton of product and growth lessons we’ll see as we break down Roku’s $9.2B media machine.

Here’s what you can expect in today’s analysis:

The Roku Story: Star Trek, Netflix, And The Popcorn Strategy

How Roku Grows: The Power of Defaults, and Building The Operating System for The Media Ecosystem

The Hardware Play: Roku’s Trojan Horse, And Thinking in Layers

The Platform Play: The Power of Defaults

The Native Content Play: Roku As The Publisher And Content Owner

Small ask: If you enjoy today’s post and learn something new, I’d be incredibly grateful if you helped others discover my writing. Hitting ❤️ in the header, or sharing/restacking, are all a huge help. Thank you!

Cool. Let’s get to it. 🍿

[If you’re reading this in your email, click here to read the full piece]

The Roku Story: Star Trek, Netflix, And The Popcorn Strategy

In the mid-1990s, around about the same time I was driving my parents up the wall with colic, entrepreneurially-spirited Anthony Wood had a problem: how to record his favorite TV show, Star Trek, without the frustration of physically taping each episode and managing a growing collection of VHS tapes.

After spotting an ad for hard drives in his local paper, he connected some mental dots and created the digital video recorder (DVR), releasing ReplayTV in 1999. Just 2 years later, he sold it for $110M.

But, in solving this problem for himself and by being immersed in the world of video recording, he found inspiration to work on something far more ambitious: Making it easy for viewers to watch what they want…whenever they want. This led to questions like, “What if there were a better way for more creators to deliver great content to the audiences they want to reach?”, and “What if marketers could unlock greater value by combining the power of TV with the precision of digital advertising?”

Nobody but Anthony was really asking these questions back then.

At the turn of the millennia, more than 80% of households in the US were connected to traditional paid TV services (via cable/satellite) offering hundreds of channels. Blockbuster Sundays were booming. And sitting on your couch watching the first X-Men (2000) must have felt like the future of TV had arrived.

But, despite being in a world of dial-up connection, Anthony saw a more advanced future, believing the internet held the potential to transform TV completely. Indeed, he was right.

He knew that to make that vision a reality, the non-connected TV would need an operating system—a box for the box if you will.

No stranger to starting businesses, Anthony founded Roku in October 2002 (Roku, meaning “six" in Japanese to represent this being his 6th company) as a startup on a mission to connect TVs with a media player that doubled up as a “smart” operating system. And this was all 5 years before the first version of what we now know as a Smart TV hit the shelves. 💡

To make it happen, he approached a little underdog entertainment company sending DVDs to folks in the mail.

The Netflix Player

When Anthony came to Reed Hasting with the idea of creating the world’s first and only purpose-built TV OS—transforming the television set from a simple one-way receiver into an internet-enabled device connecting viewers to a growing library of content available online—Reed……wasn’t convinced.

It took a month of pestering for him to get behind the mission of bringing together and benefiting the entire TV ecosystem. When he finally did, he wanted it to be a Netflix product. So, he bought Anthony in to develop the video streaming box in-house. Wood took a part-time job to create the device at Netflix while remaining CEO of Roku (which at the time, was actually focusing on an audio streaming product).

They codenamed the top-secret project “Griffin,” after Tim Robbins’ character from the film “The Player.” Because, not so covertly, that’s exactly what they were building, The Netflix Player: a plain little black box that Netflix subscribers would hook up to their TVs to stream from the web.

As the project progressed, Reed began to see how this idea could fundamentally change how his then $200M startup could distribute content to their 800K customers, who were used to waiting days for DVDs to arrive by mail.

The big picture came into sight: Netflix could leverage the digital content deals they were striking with studios to dominate the living room with watching efficiency and optionality for the viewer.

Yet, despite that vision and all the years and dollars invested into building the device, in December 2007, just weeks away from launch, Reed cut the wings on project “Griffin”.

Why?

Correctly, Reed realized that if Netflix shipped their own hardware, he’d complicate their partnerships with other hardware makers in the future. I.e, if he wanted to pick up the phone, call Jobs, and get Netflix on Apple TV, that wouldn’t happen if Netflix was in the hardware business. As Anthony recalls:

We were getting so close to shipping the hardware, and Reed decides, “I changed my mind–I don’t want to do hardware anymore. If we ship our own hardware, it could be viewed as competitive”. Putting all that money into it; getting it as far along as he did; and then deciding we’re not going to do it? Wow. I was surprised. There was so much momentum inside the company.

So, in one of the riskiest moves in Netflix’s history, he spun out the media player division to Anthony, giving him the device, patents, and Netflix team who were working on it. In return, Netflix got 15% equity in Roku and was able to remain an agnostic platform. [They later sold that stake for a mere $6M.]

A few months later, in May 2008, the first Roku model hit the market with a single default channel installed, Netflix. It came at an attractive price point, and just as the streaming revolution was about to kick off, it had a little black box ready to support it all.

Suddenly, people at home could add more than 50 channels to the Roku player, including Major League Baseball and Amazon Video. Viewers loved it, and the future was starting to look different.

While Netflix is often crowned by the masses for bringing streaming to the TV (because that’s the content they were streaming), really, the notion of it all was pioneered by Anthony. But he doesn’t mind…he’s too busy selling popcorn.

What’s popcorn got to do with it?

Despite Roku’s revolutionary product, great user feedback, and Anthony’s proven track record as a founder, they struggled to raise outside money. Simply, because Silicon Valley saw Roku’s physical little box, and VCs are notoriously bearish on hardware companies. Why?

Well, hardware can often be easily replicated and often costs nearly as much to manufacture and market as it ends up selling for. And—through that lens—they were absolutely right. Even today, Roku’s hardware is a loss leader. AKA, they lose money on every device sold.

Seemingly a bad business model…unless you’re not really in the hardware business.

And that’s what Menlo Ventures’ Shawn Carolan saw — realizing everybody was seeing trees, and missing the vast forest that came from a services-based strategy. As Shawn says:

I remember this PowerPoint deck I presented around 2009/2010 where I kind of laid it all out [for the partners]. We called it our popcorn strategy, because movie theaters don’t make money off movies, they make money off the popcorn.

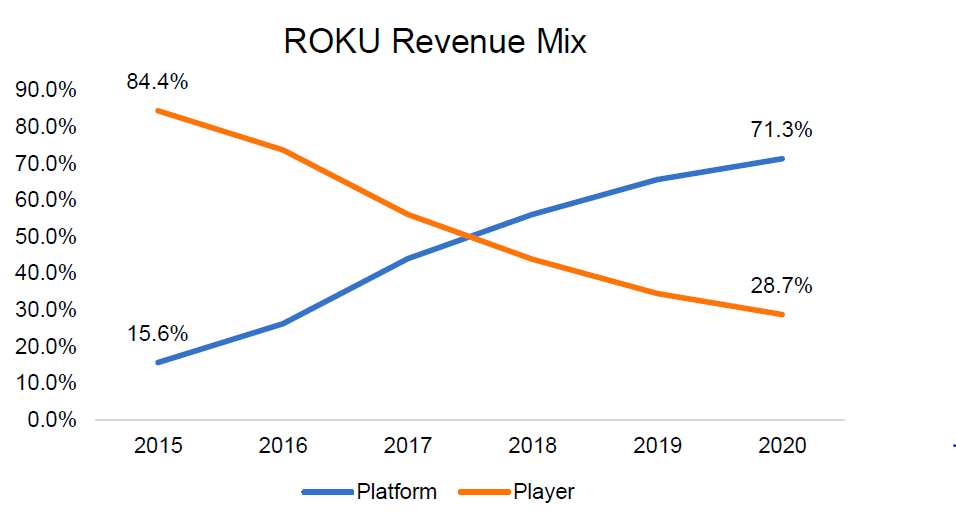

When looking at the numbers, it’s easy to see how (despite Anthony pitching Roku as a platform business) investors persisted otherwise. Just look at their revenue mix back in 2015. Five years earlier, platform revenue was likely not even being counted.

Luckily, Shawn bought into Anthony’s vision that this hardware was simply a wedge.

And with institutional backing, Roku was off to the races. Over the following years, they solidified their positioning as an operating system, grew their distribution advantage through players, and differentiated themselves in an increasingly crowded streaming market. As they sold more hardware, they began to think more like a movie theater—lose money on tickets to grow the audience and build out an attractive concession stand with new margin-enhancing services. 🍿

Today, with over $3B in annual revenue (the increasing majority coming from platform revenue), nobody is confusing Roku for a hardware company.

On that note, let’s go deeper.👇

How Roku Grows: The Power of Defaults, and Building The Operating System for The Media Ecosystem

First, let’s set the 30,000ft view of Roku’s strategy. Conveniently, we can break it down into three broad prongs:

Roku uses affordable and convenient hardware (via direct sales and licensing partnerships) to acquire consumers, get into the living room, and break into as many TV sets as possible. Like the iPhone, this gives them tremendous control over distribution.

Then, once Roku’s software (which comes on their hardware) controls the TV set, it becomes a viewer’s default home entertainment operating system. This allows Roku to capture viewers’ attention the moment they hit the On button, thus, serving as a key platform for video streaming. And as the base layer, they can enjoy diversified revenue by selling services to all stakeholders across the media ecosystem.

Finally, as the OS with the biggest market share, Roku now controls supply and demand. This unlocks bargaining power with partners and the ability for Roku to launch its own original content streaming product, with better ad revenue margins.

Using this as our roadmap, let’s start by breaking down the first prong of Roku’s strategy.

The Hardware Play: Roku’s Trojan Horse, And Thinking in Layers

There are a lot of players in the media ecosystem. And media/entertainment is a notoriously cut-throat industry. Combine that with the difficulties of scaling a hardware product that loses money on each sale, and we reach a logical question…how on Earth did Roku break in so successfully?

That’s the central question we’ll answer as we look to understand the first part of Roku’s go-to-market: the hardware play.

At the heart of it was presenting Roku as an agnostic platform that was uniquely positioned to help everybody—primarily, content publishers (Netflix), TV manufacturers (Hisense), and retailers (Walmart)—reach new and existing customers in a better way.

From 2008 through 2012—the first phase of Roku’s hardware go-to-market—they focused on producing external streaming devices (like versions of the original box and USB-style Roku sticks). These products worked with a TV. As you can imagine, this came with a few different challenges: (1) they needed to convince the customer they needed a streaming device in the first place, (2) that they should choose the Roku box/stick over competitors, and finally, (3) once they buy it and it’s plugged in, they should use it when on their TVs.

Then, just as smart TVs (AKA, modern TVs that connect to the internet) were becoming a thing, Anthony saw how this emerging tech threatened to make their products obsolete, and, ingeniously, he confidently walked Roku into the lion’s den with a brilliant idea.

Instead of competing with the TV providers, he positioned Roku as a valuable partner. How?

Well, TVs are a very thin margin (~1-2% operating margin) business. This means every cost matters, a lot. Roku’s strategic stroke of genius was partnering (non-exclusively) with cheaper TV providers like TCL who were targeting more price-sensitive consumers. Meaning, they were even more conscious of delivering TVs to the end customer at an affordable price. Instead of building and maintaining their own operating system, they could make their TVs smart at a fraction of the price. And this cost-saving value proposition also helped co-brand Roku TVs win over one of the most powerful players in the media ecosystem—the retailers like Walmart and Best Buy, the gatekeepers for TV distribution in America. Since TV features are hardly differentiated, one of the most differentiating factors retailers consider, in terms of who gets shelf space, is price. Anthony explains these dynamics well:

Our software runs on low-cost TVs, and it costs less to build a TV with Roku software. When you’re trying to get 50 cents off your bill of materials so you can win a Black Friday special at Walmart, the amount of money you save by cutting your RAM in half and your CPU in half by running Roku software — which actually has great performance and more content — is huge. It’s the difference between getting distribution and not getting distribution in Walmart.

This was the ingenious Phase 2 of Roku’s hardware go-to-market: Channel partnerships with smart TV makers. Now, customers didn’t need to buy TVs and Roku devices, rather, Roku came with the TV thanks to them licensing their operating system out.

This makes the consumer’s life much easier, as well as saves them the cost of an external device and brings the cost of their smart TVs down. And for Roku, it allowed them to tap into the distribution efforts of companies like Hisense and TCL who were investing (and competing) heavily in winning market share in this emerging market. Instead of Roku needing to worry about their own shelf space in retail, they now could sit back, watch the fight go down, and just piggyback on everybody else’s growth efforts to get into the living room. Anthony knew the OS of the TV would likely be far more durable than any particular TV OEM. 🧠

As you can imagine, this second leg of their GTM was a wild success, largely, because they got in at the bottom, just as the smart TV wave was getting started.👇

Today, 1 in 3 TVs sold in the US are Roku TVs. What’s more, by integrating with the TVs and serving as their operating system, Roku solved all three of the hardware challenges they had in Phase 1:

They didn’t need to convince anyone to get a streaming device, as it was now part of the TV

They didn’t need to convince anyone to choose Roku over competitors, as Roku came installed on multiple competitive TV brands

They didn’t need to convince people to navigate to Roku’s external device, because simply by turning on the TV, viewers were using Roku already

Basically, all three challenges merged to just one: make sure consumers are buying co-branded Roku TVs.

Because, once they have one, Roku can enjoy the power of being the default platform for a large installed base of active users. Honestly, this was Roku’s most strategic move yet and brings us an excellent lesson on the power of channel partnerships. Specifically, the distribution advantages you can gain.

Question: Who is big in your market and serving the same customers you’re trying to reach? Can you imagine a way to somehow package/integrate your product with theirs that’s valuable for both of you?

The Platform Play: The Power of Defaults

From the beginning, despite resistance from the naysayers, Anthony knew Roku’s hardware business was just a means to becoming the centralized distribution hub for all digital TV.

Now, when talking about platforms, there are two definitions I love. Tim Sweeney (from Epic Games) says “You’re a platform when the majority of content people spend time with is created by others”, and Bill Gates says a platform is “When the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it.”

In Roku’s case, both definitions are certainly met. However, more importantly, they allude to something else: It is the ecosystem that makes a platform so powerful.

And with an ecosystem—as we saw in our deep dives on Roblox, Epic Games, Stripe, and Shopify—it produces powerful barriers to entry that make a company formidable in the market.

Usually, those barriers to entry come in the flavor of some sort of network effect (AKA, the more people that use it, the more valuable the product becomes). The five largest companies by market cap in the US all seem to be built on a type of network effect (of which there are many). Some pundits even go so far as to claim that 70% of tech value creation since 1994 is predicated on network effects.

But, with Roku, there’s a more interesting, less covered, and arguably more powerful economic moat worth talking about. It’s the end state that network effects can enable, and exceedingly few companies get to enjoy: Defaults. 👇

Roku’s power and defensibility: The moat of all moats ✊

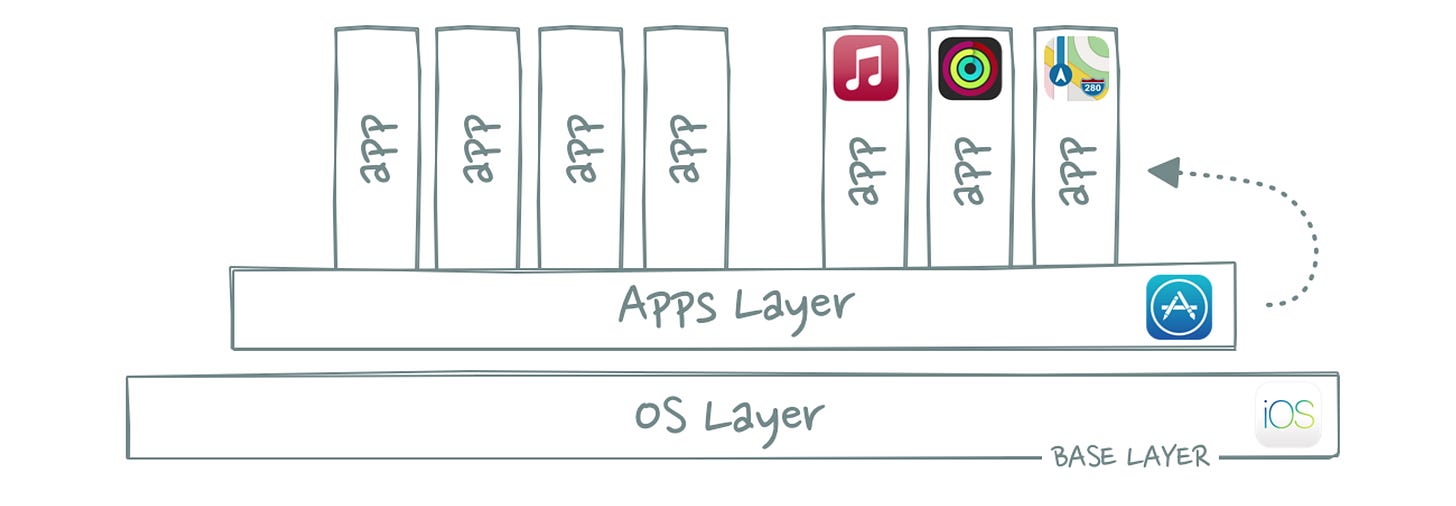

To understand the power dynamics between different platforms, aggregators, and other players in a tech ecosystem, it’s helpful to look at them as a vertical stack with different layers.

At each layer, companies are trying to create value for customers and capture value for their bottom lines. The lower in the stack you go, generally, the more valuable the layer will be. Why?

Because whoever controls a layer has huge bargaining power and leverage, allowing them to call the shots for how value creation and value capturing are happening in the layers above them. For example, big-box retailers like Walmart control the retail distribution layer, allowing them to dictate the terms—ultimately deciding who lives and dies in the consumer goods world. Amazon does that online.

Subsequently, we often see:

Companies adding layers on top of their existing business (thus, giving them platform power)

Companies moving down the stack to get closer to the base/bottom layer

The base layer, simply, is the last UI in the stack that we as end-users deal with. In tech, this is usually an operating system connected to hardware. In our lives, there are very few base layers we deal with. A safe bet would be, wherever you are in the world, that whatever base layer you use comes from either Apple, Google, or Microsoft.

Speaking of Google and Apple, here are two very interesting examples by Julian that make this concept of layer-thinking more tangible. As you read through them, watch out for the similarities in Roku’s business model.

a) Google’s layer, and default

Google started as a simple website that allowed users to search other websites. Thanks to the superiority of its PageRank algorithm, more and more users started using Google Search, resulting in better search results and thus in even more users switching over to Google Search.

Thanks to this powerful data network effect, Google was able to move down the stack. Google wasn’t “just a website” anymore, it became an aggregator that commoditized all other websites and made them layers on top of Google’s.

The data network effect, however, is not the real moat here. It’s just a means to an end. The end goal is to become a default on the layer below.

If Google wants to become a default on the layer below the search engine, it must find and occupy limited real estate on the browser layer. There are billions of websites out there … but only one default: Your browser homepage.

Becoming the default browser homepage became Google’s actual moat. There can only be one homepage (no multihoming) and users are typically too lazy to change it (friction = switching costs).

As you well know, Google didn’t stop there. It moved down the stack and successfully conquered the browser layer with Google Chrome – which obviously shipped with Google Search as the default search engine. More importantly, it turned the address bar into a search box thereby melting the browser and the search engine into sort of one layer.

With Android – one of the most underrated acquisitions of all time – Google then moved even further down the stack. It now owns a significant chunk of the world’s most important base layer: the smartphone operating system. Unsurprisingly, Android ships with Chrome and Google Search pre-installed.

If you think about it, it’s kind of amazing that the largest operating system humanity has ever seen only exists to protect an advertising business two layers further up the stack.

Simply, Google started with an app and used its network effects to move down toward the operating system base layer. Apple approached it inversely, and its strategy is more akin to Roku’s. 👇

b) Apple’s layer, and default

The first iPhone was released in 2007, but only in 2008 did the company launch the App Store. Opening up iOS to third-party developers created a new layer above the operating system: apps.

The apps layer is interesting because it created indirect network effects between developers and users, which added defensibility to the OS layer. That defensibility in turn meant that Apple was able to capture a lot of the value that was created on top of its platform. 30% to be exact.

30% value capture is great, but you know what’s even better?

100% value capture.

Over the last couple of years, Apple has increasingly launched and monetized its own apps (and services) on top of iOS. It has moved up the stack and is now competing with the third-party developers on its own platform.

In contrast to third-party apps, however, Apple’s own apps come pre-installed. They are defaults.

Apple realized that it owns some of the most valuable pixel real estate in tech: The home screen. And the best way to monetize that real estate is by occupying as much as possible of it yourself.

The beautiful thing about defaults is that they beat almost any competing product – even if that competitor has strong network effects or is technically superior.

This is why Apple Maps has higher market share than Google Maps, why Apple Music is able to catch up with Spotify, and why Google pays Apple $15bn a year to remain the default search engine on Safari.

If you’re reading this in your email, this post is about to get cut short. Hit the button below to continue reading.

Roku’s layer, and default

We haven’t spoken yet about how Roku has taken one from Apple’s playbook by adding their own apps layer on top of their operating system layer (we will soon). But here’s how to view Roku’s business in vertical layers. 👇

For now, the key takeaway is that Roku controls the limited real estate of the homepage across ~30% of American TVs. In the media ecosystem, that gives Roku a ton of power as the gatekeeper with all the partners above them.

This begs the question…shouldn’t Roku be the ones paying the TV manufacturers to be their OS?

Perhaps, which is why it’s a little surprising to see them expanding their product line to include a range of smart TVs that are the first to be both designed and built by Roku. This would give them absolute control over that hardware layer, and I assume more revenue from TV sales than OS licensing. However, while I’m no expert, I wonder if that move is too greedy, and it could expose them to losing relationships with their essential OEM TV partners.

In this bold move, the comparatives would be Google’s strategy with Google TV or the Google Pixel phone, and Amazon’s with Fire TV. A calculated risk by Anthony, I’m sure, but I’m curious to see how (if at all) this stirs Roku’s existing ecosystem up.

…

Okay, now we already know just a fraction of Roku’s revenue today comes from their hardware/licensing business, even though that’s the actual source of Roku’s power, and moat.

So, to understand where their $750M Q1 ‘23 revenue came from, let’s go back to the movie theater and concessions framework from earlier.

Roku’s popcorn 🍿

One of the best ways for platforms to monetize is to collect “rents” from all the third parties that build on top of it. Or, all the products in the layers above.

This model works well because it allows folks like Roku to directly benefit from (1) all the value that they create, and (2) the investments that all their partners (Netflix, etc) are making to create value for their own customers, thus, giving Roku access to their total addressable markets.

Within the OTT ecosystem, there are generally three “rental” models. And you guessed it, Roku is diversified across all three:

Streaming Video-on-Demand (SVOD) lets users subscribe for unlimited streaming

Through Roku’s platform, viewers can search for and discover streaming services, from popular ones like HBO to more niche ones like Crunchyroll. And if a user ends up subscribing to one of them—as the marketplace provides marketing, customers, and the ability to transact—Roku gets a cut (~20%) of the new subs they generate for as long as the viewer stays subscribed.

Transaction Video-on-Demand (TVOD) lets users rent/purchase once-off content

Just like when you pay that $20 for the latest release on Amazon, Roku monetizes from viewers purchasing one-off content. Similarly, Roku keeps about ~20-30% of the transaction value from the content publisher.

Ad-supported Video-on-Demand (AVOD) lets the user watch for free (or cheaper) in exchange for annoying ads

Because ads are such a massive part of Roku’s business, let’s give it a bit more focus.

Roku’s cash cow 🐄

This shouldn’t surprise you one bit. TV advertising is a big fucking business. Globally, $173B to be exact. Of which, $71B is in the US. And with consumers caring more and more about price, while facing subscription pressures from multiple services (as illustrated by Netflix buckling to an ad model), the AVOD market is only getting bigger.

In other words, as the gatekeeper of OTT content, Roku is in a wonderful position to capitalize on it as both ad volume increases (yay), and TV-watching hours shift from linear to streaming.

This is exactly why in 2017, they diversified their platform revenue for a third time by launching their self-serve ad product, allowing folks like State Farm to start sending Jake to our tellies. Within just 5 years, it already accounts for ~73% of their total revenue. Someone got a bonus.

Now, forget us—the consumer who just wants to watch a show in peace—for a second. The shift from linear TV to AVOD is way better from an advertisers’ perspective. Simply because the depth of first-party data that platforms like Roku have is orders of magnitude better than the data cable companies had. As a Roku employee said:

I'm literally looking at a spreadsheet right now where we have something like 400 different audiences. There is like whiskey drinkers, people who have a high propensity to potentially be diabetic, just all that data that you have access to through digital.

This makes for better targeting, thus more performative ads, and in turn, drives more ad spending. Good stuff for Roku’s business.

As a quick aside/vent: All I’ll say about these “state of the art CTV ads” is this…I don’t need arthritis medication. Please…stop badgering me.

Anyway, to keep fortifying this massive business area (and hopefully stop sending me irrelevant ads), Roku acquired Nielsen. To avoid going into AdTech lingo, in short, this beefed up Roku’s data and analytics capabilities (data network effect), giving marketers the power of far more personalized and contextual ads.

And on that note, let’s go a little deeper to see how Roku is growing their ads product.

Contextual (and shoppable) ads, at the right moment, using AI

As I just ranted about, ads that are irrelevant, repetitive, or, overly-targeted and intrusive are bad for business. With the AVOD model, it’s important Roku strikes the balance in order to not hurt streaming hours. To this end, in May 2023, they of course introduced a new AI layer to ads.

What they’re doing with AI here is actually pretty cool. It’s all about context, and running ads right next to the most relevant moments in shows and movies. For now, this is isolated to their own channel where they have more first-party data.

As they explain it, the AI searches for “iconic plot moments” that would match a brand’s message and place their ads in real-time. First, marketers tag their campaign’s theme, then, the AI searches the library to match the campaign with key moments.

On top of that, Roku partners with ecom companies like Instacart, DoorDash, and Best Buy, for more shoppable ads, allowing viewers to purchase items with their remote or voice— shortening the distance from discovery and inspiration to purchase.

Growing Roku City

Generally, when a TV starts to hibernate you get some montage of landscape photos before a black abyss. But, if you let a Roku idle long enough, you’ll soon be transported to a dreamy cityscape. This is a lovely example of a brand pushing standard design philosophies to create something magical for the user, even though it solves no problem. Even when there isn’t a movie on-screen you can still be entertained by their virtual city, with billboards and that’s full of Hollywood easter eggs.

What started out as just a fun design choice with no real strategic goal, has now taken on a life of its own. On social media, it’s become known as Roku City, and apparently, the mention of it occurs once every 11 minutes on Twitter.

While originally Roku City would just suggest content to stream, it’s now being weaved into their ad business. AKA, don’t be shocked to see the golden arches of McDonald’s in there.

All in all, Roku has become the US leader in streaming distribution. In large part, they’ve won default status thanks to remaining agnostic in the media ecosystem. However, this “We’re Switzerland” image has recently been changing.

Despite the power of controlling demand via its platform, Roku understands the value of content. At the end of the day, that’s what we remember and talk about. That’s where there’s affinity to a brand—not towards the OS. It’s for that exact reason that we assume Netflix pioneered streaming, failing to give Anthony and Roku fair credit.

Roku’s recent push upwards from their base layer with The Roku Channel, into the app marketplace with their partners, shows us that Roku knows that what got them from “1 to 10” may not be enough to get them from “10 to 100”. And as a public company…that’s what the market demands. 🤌

With this native content play, they’re following Netflix’s go-to-market of licensing content from others to flesh out a library, as well as opportunistically acquiring content where they can…like buying Quibi (Read: Why Quibi Died).

With this third and final prong of Roku’s strategy, the end game is hardly agnostic.

We do think the future is a different UI, which is more content-focused. More recommendation-focused. And we have that UI! It’s called the Roku Channel… The Roku Channel is our sort of sandbox for building a next-generation, content-first user interface. And someday, when we think it’s ready and good enough and has enough content in it, it’ll probably become the home screen

— Anthony Wood

Let’s dig in a bit more in this final chapter.

The Native Content Play: Roku As The Publisher And Content Owner

In September 2017, Roku entered the streaming wars by launching their own first-party, ad-supported, app: The Roku Channel (TRC).

At first, it was full of low-quality content that other platforms and studios didn’t want. But, that’s changed. Today, it’s a significant piece of Roku's platform business. In short, they aggregate content from other ad-supported media companies, license a large library of content (including theatrical releases from the likes of Lionsgate), and even dabble in their own originals, like Weird: The Al Yankovic Story, starring Harry Potter.

And as their library of content has improved, Roku clearly sees their channel as more than just an added piece of free value to users of the Roku OS, given they’ve launched it as a standalone app and rolled out a premium subscription offering on top of it.

This is a great example of how free, added, or unexpected value can differentiate your product from competitors, attract new users, and enhance customer loyalty.

Now, the first advantage Roku has in building up their own channel is obvious: traffic.

Owning the homepage and having an existing audience visiting it daily unlocks huge efficiencies in driving people to Roku’s content. Of course, it comes preinstalled and gets preferential placement (like those Apple apps). AKA, unlike competitors, there's no discovery or installation problem.

Then, there are two other important flywheel-like advantages that put TRC in a strong competitive position as a streaming service. They both leave us with a simple lesson: Those with more data (usually) win. 👇

Better content recommendations → more users → more data →

Roku knows a lot more about its own audience's viewing habits than a stand-alone ad-supported streaming service. Most AVOD channels (think Freevee, Pluto, Tubi) don't require users to create or log into an account. As a result, there isn’t an identity layer with user data, generally leading to terrible recommendations.

Since Roku has viewing data across their own channel, as well as insights into which channels people watch and what they search for, they can generate way better content suggestions. This makes The Roku Channel more engaging, allowing them to capture more streaming hours. In turn, driving more data and, thus, better recommendations.

Plus, they’re also using this data to figure out which content to buy/license, as well as produce. This will keep beefing up the quality of their content library, subsequently growing their streaming hours. As a result, they’ll get more data which will drive further investment in more/better content.

So, over time, Roku will be even more efficient at driving traffic into its own channel based on more content, better algorithms, and better opportunities to monetize. For this reason, I think Roku is well-positioned to gain an outsized share of ad revenue that will continue to flow heavily into ad-supported TV.

Speaking of which…

More targeted ads → more money → better content → more user →

The same first-party data that makes Roku’s content recommender strong also improve their ad targeting abilities compared to their free-TV competitors’.

And the better that marketers can pinpoint the right people—combined with Roku’s ability to deliver contextual, in-moment, campaigns—the more they’ll invest their ad budgets there compared to folks like Pluto. What’s more, third-party streaming apps may be able to offer their own ad inventory to Roku's ad-buying platform. Meaning, essentially using Roku for their ad distribution.

Why would they do that? 🤔

Well, Roku is the master of strategic partnerships, and they demonstrated it again here with their 50:50 revenue split with content providers. Because of that model, some providers may even end up generating more revenue per streaming hour in TRC than within their own app.

But won’t Netflix and Co. get salty about this?

Of course, Roku needs to be careful. Content publishers are still essential to their value proposition to the customer, and if they compete too hard against all of their partners it could put them in a precarious position.

But then again…Roku is only making this push into content because they have substantial leverage. Remember, Roku is the default homepage for 1 in 3 Americas.

If media companies don’t want to work with Roku, where else can they turn for distribution? Netflix needs to be accessible on the Roku homepage, period. Plus, the other companies offering base layer operating systems on the TV (Apple, Google, Amazon) are bigger long-term threats to their own content business with rich data and insane spending power. Google right now not so much, but Apple and Amazon are clearly very serious about being media companies with top-shelf content.

In other words, Roku gets to keep using the “We’re just the little guy!” approach. Even though they’re not so little and have a ton of leverage across the ecosystem.

And that’s the power of defaults, baby.

To wrap it up with a single closing thought…

Roku’s strength was originally attributed to the rich integration of hardware (part 1) and operating system (part 2)—giving them default status as a platform. But recently their tight integration has expanded into first-party user-facing applications (The Roku Channel) and more “popcorn” services (better ads), the distribution of third-party channels, digital payments, Roku TV sets, richer user data, and even their own line of smart home products (speakers, cameras, etc). This growing bundle doesn’t just give Roku more profit streams and make its ecosystem more attractive to consumers, content publishers, advertisers, and retailers, but it also arms Roku with considerable hard, soft, and even accidental power.

And that, guys, is a wrap on Roku.

Thanks so much for reading! I really appreciate your time a great deal, and I hope in return you learned something new today.

If you did—and you enjoyed this post— I’d be super grateful if you gave it a like, share, and if this was your first time reading, subscribe for more.

Until next time.

— Jaryd ✌️

Fantastic read!

I am curious about the Roku City move as well. As you mentioned, ads are a fairly possible & potentially big opportunity. If they are able to do it in a seamless & aesthetic way, this could be a great new revenue stream.

On mobile, companies like Glance have used lock screens engagement to build a fairly useful consumer product & ad channel.

This was a fantastic piece to read! Would love to see more of these “underrated” gems in how they grow as the publication grows.