🌱 5-Bit Fridays: Unconventional operating principles, how not to be fooled by viral charts, applying leverage, equations that don't work, and lessons on leadership from Amazon

#42

👋 Welcome to this week’s edition of 5-Bit Fridays. Your weekly roundup of 5 snackable—and actionable—insights from the best-in-tech, bringing you concrete advice on how to build and grow a product.

To get better at your job, drop your email here and join 9K+ others for weekly insights.

Happy Friday, friends 🍻

In case you missed it this week:

Folks have spoken about how the “vibe-cession” is over. But, a key recession indicator has been flashing red for months. The 10-year and 3-month yield curve has been inverted for 212 straight trading days, which may suggest an economic recession is imminent. Great.

On “Wall Street”, grocery delivery giant Instacart is set to price their IPO at a $10B market cap, from $9B. Which, FYI, is about 20% of the price of last funding round valuation.

The odds of Apple and the iPhone being unseated in the US are next to none—they have a cult like following and incredible product (despite the boring iPhone 15 release). But, Mode’s EarnPhone is the biggest disruption to smartphones in 15 years. TL;DR: it literally pays to user your phone. Their budget smartphone has helped consumers earn and save $150m+ for activities like listening to music, playing games, and even charging. Just incase that recession comes along?

It looks like paying up for celebrity/influencer endorsements works. Apparently, celebrities increase consumers willingness to pay up to 29%.

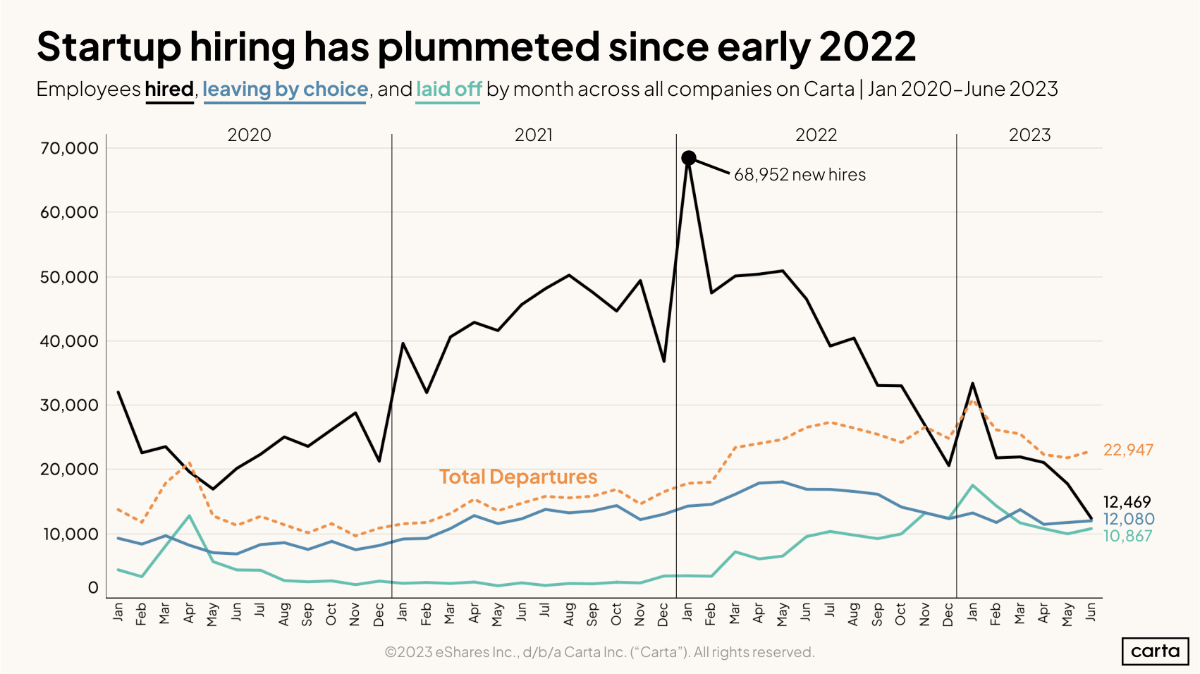

Startup hiring has plummeted. Carta Insights reveals the current hiring market for startups is stuck in the mud. Look at the black line to see the decline, and the orange line above the black line from Feb shows net declines in headcount.

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

Unconventional operating principles from Nvidia’s Jensen Huang

How not to be fooled by viral charts

A lesson on leadership from Amazon

Equations that don’t work in product management

Applying leverage as a product manager

Small ask: 👉 If you enjoy reading this post, feel free to share it with friends! Or feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post so more people can discover it on Substack 🙏

(#1) Unconventional operating principles from Nvidia’s Jensen Huang

2 weeks ago we went deep into Nvidia’s story and growth strategies (read: How Nvidia Grows). If you read it, you’d have noticed me fanboying over their unsung hero CEO, Jensen Huang.

As I wrote: “He is one of the best strategic executors I’ve come across”.

Jensen has an knack for spotting huge opportunities and trends before other people, understanding the market and Nvidia’s advantages, and taking no qualm making big bets toward ambitious strategic visions.

In today’s first bit, I want us to zoom in from Jensen the strategist to Jensen the operator. And the way he runs Nvidia’s trillion dollar empire brings us several unconventional approaches to operations.

Shoutout to Dan Hockenmaier for finding this gem of an interview and posting about it earlier this week.

Here’s a rundown:

Even with 40 direct reports, he’s ditched the 1:1 completely 🧑🤝🧑🧑🤝🧑

He believes that the flattest org is the most empowering one, and that starts with the top layer.

He’s completely ditched the typical 1:1, and leans into group meetings as they are more collaborative

He gives no career advice. As he says, "None of my management team is coming to me for career advice - they already made it, they're doing great”

My thought: I think the caveat here is that Jensen is very high up in the org. He’s CEO, and 40 1:1s would take up way to much time. For other managers, I believe 1:1s are still an important function. They help with direct coaching, private feedback, and relationship building. Don’t be so quick to drop them

No status reports. Instead, he “Stochastically samples the system” with random inspections of things 🕵️♂️

He believes the classic status update is too refined by the time he gets them and misses important details. The real nitty gritty truth gets lost. Instead, anyone at Nvidia can email him their "top five things" and he’ll read it. He reads ~100 of these everyone morning.

My thought: The takeaway for me here is that no matter how high up you go, never lose connection with the product and the nuts and bolts of operations by relying on updates. There’s a ton of value in getting your hands dirty.

He’s a firm believer in radical transparency and making sure everyone has all the context 📖

None of his meetings are siloed off. Even if he’s meeting with execs, anyone can join and contribute if they want.

"If you have a strategic direction, why tell just one person?"

"If there is something I don't like, I just say it publicly"

"I do a lot of reasoning out loud"

My thought: Couldn’t agree more. Context and over communication is king. This allows for information to travel as quickly as possible.

Surprisingly for such a strategist, he’s ditched formal planning cycles 🗺️

He has no 5 year plan. Not even a 1 year plan.

He’s always re-evaluating based on changing business and market conditions

My thought: Writing a strategy memo and putting a nice deck together is great, but often folks thinks that’s the planning for the year done. Micro and macro context changes regularly, new customer insights come up, and new tech like AI changes insanely fast. Plans need to be fluid and regularly reevaluated.

(#2) How not to be fooled by viral charts

Oh boy, have I been duped by charts on Twitter and TikTok before.

Here’s how it goes: You see a graph online, you think, “Holy shit, that’s crazy”, and you walk away with a new opinion that you tell your friends.

Charts are data. Data is “truth. And “truth” is what we base our views of the world on.

Except, often the “truths” charts bring us is bullshit.

And unfortunately, we’re pretty bad at figuring that out and catching the BS. I am, and considering folks like the WSJ, The Financial Times, and leaders like Nancy Pelosi are too—I’d bet you also are.

So, in a world riddled with fake news and misinformation, take this critical post by Noah Smith as an important PSA. 🚨

Noah Smith , my favorite economic commentator, wrote a top shelf piece earlier this week on how to identify charts that contain misinformation—whether intentional deception, careless mistakes, or just generally meaningless data.

Let’s start with this important excerpt to set the scene, because I’ll be the first to admit I was fooled by this viral chart.

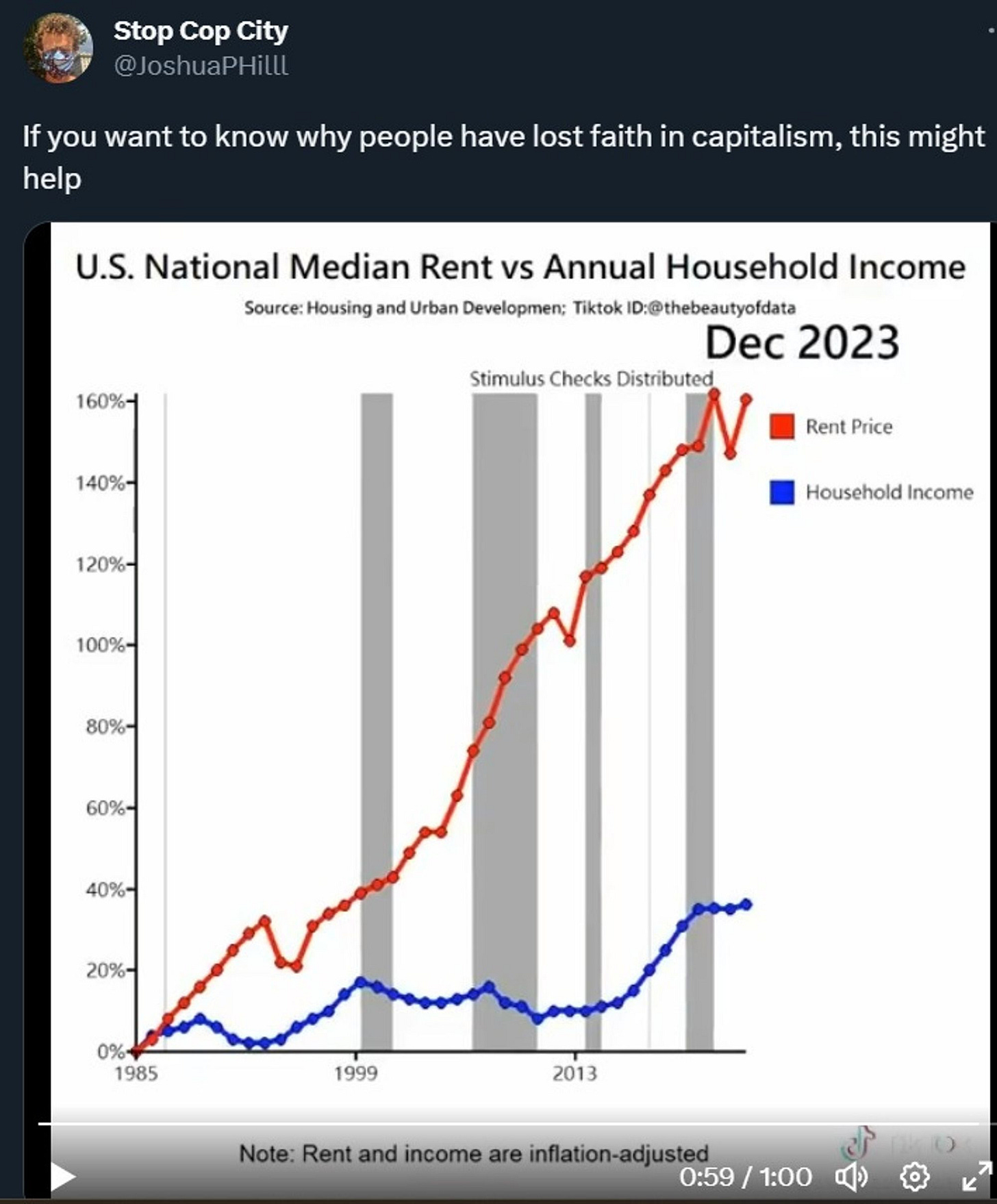

Activist and social media shouter Joshua Potash recently posted a video from TikTok that claims to show rent increasing much faster than household income since 1985:

This chart is completely wrong. Although it says “Note: Rent and income are inflation-adjusted” at the bottom of the screen, this is either a mistake or a lie. Only income is inflation-adjusted. The red rent line is not. A community note has since been added, pointing out the error, but not before Potash’s tweet was able to rack up an incredible 77,000 likes and 17,000 reposts.

Comparing an inflation-adjusted (or “real”) economic number with one that’s unadjusted (“nominal”) is one of the easiest ways to make a graph that turns heads and gets clicks but which is complete B.S. If you compare an inflation-adjusted number to one that’s not adjusted, there will be a big gap between them over time. Instead, to make an apples-to-apples comparison, you should always compare either two adjusted numbers or two unadjusted numbers.

Let’s go to FRED, the data page maintained by the Federal Reserve, and see what the true numbers are. Let’s compare median household income with the Consumer Price Index number for “rent of primary residence”, which is the standard number for average nationwide rent. And let’s set them both equal to 100 in 1985 (which is where Potash’s chart begins), so we can look at the percent increase. Here’s what we get:

There’s no big divergence here at all; the two numbers track each other very closely.

The takeaway here is clear. While the narrative and the vibe tell us otherwise—rent and income have largely kept pace with each other in America.

This is just one example among and ocean of other charts that lead to erroneous understandings.

Question: How much does the US government spend on the military?

It’s a ton right. 👇

“About half” is the popular narrative thanks to charts like that.

That chart isn’t wrong, but, the US. separates its federal spending into “mandatory” and “discretionary” for political reasons, and puts defense into “discretionary”. So people will share charts like the one above which is of only discretionary spending and use them to claim that defense represents the bulk of the total, while in fact it’s only about 12%.

That’s still a lot, but it’s not half.

So, how can we avoid getting caught by charts like this?

As Noah puts its: “You’re basically on your own out there, with only your wits to protect you, in a world of people who want to get your clicks and eyeballs.”

So, here are a few of his tricks to help you spot bad data and keep your wits about you when seeing charts like this.

Be skeptical of dramatic graphs; check to see if they’ve been debunked. The more eye-popping and startling they are, the more likely it is that there’s something fishy going on. As they say, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

Pro tip: Go check Reddit to see if someone has already debunked the graph. Try using Google reverse image search to see if there’s a thread.

“Another good sanity check is to think through the implications of a chart. With the housing-vs.-income chart, some quick mental math showed that it claimed that rent doubled as a percent of income.”

One folks often miss is actually checking to look at the source for the data. If a chart doesn’t have a source for it’s data it’s a red flag.

Make sure you understand what you’re looking at.

The first thing you should know about any chart is what it’s measuring. If an axis isn’t labeled, it’s a big red flag. “Some charts aren’t really charts at all, but simply visual depictions of vague ideas made up to look like charts.”

And if it does have a label, make sure you actually understand the axis label before you draw conclusions from it.

“Sometimes the issues with what a graph is measuring can be more subtle than just realizing you don’t know what a label means. For example, it can be easy to confuse percentage increases with percentage point increases.”

Check the axes, and check the data points

Even if the graph’s data is clearly defined, there are lots of misleading ways it can be presented.

“One thing to watch out for is the dreaded dual-axis chart, as you can stretch and compress your axis until you make things look like they line up more than they really do”

And lastly, as Noah so perfectly puts it:

In fact, charts that are total B.S. are much less dangerous than charts whose data is basically correct, but which get attached to misleading narratives. B.S. charts invariably get debunked in short order, whether by Community Notes or Politifact or Reddit or just by blogs like [his]. But the misleading narratives that get attached to many other viral charts can persist for years, worming their way into the minds of the public until they become indistinguishable from consensus reality. Spotting and picking apart those narratives is a much more difficult task than catching simple misinformation.

He hasn’t written it yet, but to get Noah’s guide on dealing with how to avoid falling for those misleading narratives, be sure to subscribe to.

(#3) A lesson on leadership from Amazon

When I saw Dan Hockenmaier post about Jensen’s operational views as a leader (our first bit), my mind instantly jumped back to this LinkedIn post I saw a few weeks ago by Richard Russel. Richard shared an observation from his time at Amazon as well as a practical way to bring it to your own work.

I think it adds additional, and reenforcing, value to what we just spoke about.

One meeting at Amazon changed everything I knew about leadership.

Picture this.

I’m fresh from 6 years at Google and feeling like I know what I’m about.

It’s my first weekly business review.

I’m expecting the usual suspects of team leaders and managers, sipping coffee and squinting at spreadsheets.

Instead I also see VPs getting deep into metrics.

These execs managed teams of up to 500 people.

But here they were digging into different

👉 pages on the website

👉 product lists

👉 categories

👉 regions

👉 markets

And they’re asking:

❓ What's the data?

❓ How is this working?

❓ That looks a bit weird. Why is that?

It was mind-blowing how deep in the details they were.

But why does this matter?

Because while most top leaders delegate, Amazon's best and brightest are elbow-deep in the details.

They aren’t micromanaging. They're mastering. They’re understanding.

They’re getting their fingers dirty and then taking all of this operational level detail.

They’re analyzing and synthesizing, so they really get it - and their managers are doing the same.

This is one of Amazon’s strengths.

Senior people making strategic decisions, talking to the CEO…

…but also knee deep in the details of what’s going on at the operational level.

Leadership isn’t just about vision.

It’s also about getting your fingers dirty.

So, what can you do with this? 👇

As Richard notes, a solid up skilling strategy for you and the team is to use is another Amazon principle: the Weekly Business Review (WBR)

Here’s how it works:

You set up your WBR Spreadsheet:

Create a spreadsheet for tracking.

Organize with one column for each week:

Newest week on the left.

Add a new column every week.

Designate one row for each Key Performance Indicator (KPI).

Focus primarily on your area of interest but also include relevant context.

Weekly team meetings:

Convene with your team every week.

Analyze patterns and trends in the data, and ask hard questions. Create a culture of openness and “no stupid questions”.

Aim to understand the controllable factors impacting your business.

Action steps for key observations:

Act immediately if there's a clear action to take.

If further understanding is needed:

Analyze the data to distinguish between signal (important information) and noise (irrelevant information).

Adjust the WBR spreadsheet to highlight the signal:

Add or remove metrics as needed.

Consider incorporating ratios or moving averages.

Besides fostering a data-driven culture, the outcome of doing this is the WBR becomes a tool for actionable insights, and you up skill your team into analytical experts.

Go deeper: 🧠

(#4) Equations that don’t work in product management

Aatir Abdul Rauf recently shared 8 equations (or, maxims) in product that feel intuitively correct, but are seldom actually true.

I love advice like this. I have a few of my own to add to the mix, but first let’s start with his: 👇

The more detailed the spec, the more guidance the team has

Specs need to be unambiguous, concise, and actionable. If that can be achieved in fewer words, the easier it is for the team to retain and act upon.

The "larger" the feature, the larger the impact.

Sometimes small fixes and enhancements can lead to a bigger impact than huge bets, especially if they are associated with highly frequented user paths. And there are many other factors involved for a feature to be deemed successful than it's footprint size e.g. go-to-market, problem intensity, copy, UX, etc.

The more meetings you have, the better alignment you achieve.

Sync and async meetings are important but the team needs to breathe. Every meeting has a context switch cost. Meeting overload dampens productivity.

The more prescriptive your wireframes, the lower the time-to-market.

The more "precise" I got, the less flexibility I afforded to UX designers to devise a meaningful solution. Eventually, wireframes needed to be redone, and the rework incurred wasted time.

The more people agree with you, the stronger your influence.

Democracy doesn't work well in product. Achieving universal consensus is hard and leads to stalemates. My influence was strengthened when I was able to articulate the rationale behind my decisions, accept the risks, own the failures & and credit the wins. Some chose to disagree but they committed.

The more KPIs you track, the better the product gets managed.

Finding the few metrics that align closely with customer and business success is better than trying to maintain a smorgasbord of dials on a dashboard.

The higher the engineering velocity, the happier users are.

Engineering velocity is a desirable attribute. It allows you to ship more. But users don't want code. They want more of their problems to be solved. So, if you ship "more" junk, they aren't smiling. Each poor product increment also incurs a "trust tax".

The more feedback you act on, the closer you get to product-market fit.

Feedback is an important signal for a PM to course-correct. But it's critical to filter the noise. Choosing an ICP and sift out the feedback beats that truly served the needs of the masses required an ability to distill, extrapolate, and validate. When I would attempt to act on every piece of feedback, it led to a feature spaghetti.

Here are a few others I’ll add to Aatir’s mix:

The more features you add, the more valuable your product becomes.

While adding features can enhance a product's capabilities, it can also lead to feature bloat, making the product complex and harder to use. It's essential to ensure that every feature added solves a genuine user problem and doesn't just add to the noise.

The more competitors do it, the more necessary it is for you.

Just because competitors are implementing a feature or strategy doesn't mean it's right for your product or audience. Blindly following the competition can lead you astray from your product's unique value proposition.

The more user requests you fulfill, the higher the user satisfaction.

While it's essential to listen to users, not all requests align with your product's vision or the needs of the broader user base. Prioritizing and implementing changes based on a strategic understanding of user needs is more effective than trying to please everyone.

The more data you have, the clearer the decision-making

Data is invaluable for informed decision-making. However, without proper analysis and understanding, it can lead to analysis paralysis or misguided decisions. Quality and context often matter more than quantity.

The faster you respond to market changes, the more competitive you are.

While agility is a strength, hasty reactions to market changes without strategic consideration can lead to missteps. It's essential to balance speed with thoughtful analysis.

The more you iterate, the closer you are to perfection.

Iteration is a key principle in product management. However, endless iteration without clear goals or understanding of user needs can lead to wasted resources and a product that's no closer to meeting its objectives.

The more user personas you cater to, the broader your market appeal.

While it's tempting to design for everyone, spreading too thin can dilute your product's core value. Sometimes, narrowing focus can lead to deeper engagement with a specific audience segment, creating loyal advocates.

The more polished your MVP, the better the first impression.

An MVP's purpose is to validate hypotheses. Over-polishing can delay valuable market feedback and increase the risk of building something users don't want. Sometimes, a rougher MVP that gets to the core of the problem is more effective.

The more you rely on quantitative data, the more objective your decisions.

While quantitative data provides valuable insights, relying solely on it can miss the nuances of user behavior and sentiment. Qualitative feedback, like user interviews, provides context that numbers alone can't capture.

Have any others you can think of? I’d love to hear. Drop a comment. 👇

(#5) Applying leverage as a product manager

Product managers are force multipliers.

Can we code? No.

Can we design? No.

Really, our value lies in being able to help our teams get more done and ship more product in the right direction. We research, we document, we unblock, we strategize, and we apply leverage as much as we can.

There’s the running joke, “What do product manager do?”. Sanjeev nails it.

And part of that unclarity around what PMs do, especially from non PMs, is that PMs have lots of choices in what they can do everyday— all of which produce some positive output.

This takes us to our final bit of the week. As a PM, where do you have the most leverage? Developing an awareness around this is crucial to your long term impact.

Brandon Chu (Ex VP of Product at Shopify) has an excellent Medium post on this.

He shares this handy visual.

Vision = where you’re going; the aspiration or goal

Strategy = how you plan to get to your vision in the context of the market/company/customers/product

Scope = what you need to ship to execute your strategy

Backlog = the units of work to achieve a scope

The lesson he imparts here is crystal clear:

Product managers exert the most leverage through vision and strategy — the rest is optimization.

Vision and Strategy are foundational. They provide the direction, the inspiration, and enable a group of people to execute as a team.

Scope and Backlog are optimizations. They accelerate progress towards a known destination.

Both are important, but going faster in the wrong direction is far worse than going slower in the right one. When prioritizing their focus, a PM should first ask themselves if they’ve built a solid foundation for their team to operate in. If not, that’s where they need to start.

Your goal as a product leader, and PM, is to therefore make sure that:

1. Everyone on the team knows how their work directly contributes to achieving the company’s vision. [Vision leverage]

2. Everyone on the team can explain the rationale behind why we’re approaching the goal the way we are. [Strategy leverage]

The easiest way to test for good product management on a team is to ask any engineer or designer on that team to describe the vision and strategy for their product. The coherence of their answers will give you all the feedback you need.

And remember…a strategy is not a roadmap. Roadmaps are an artifact that comes from having a strategy. They are the tactics that tie back to some strategic pillar. Real strategy should answer what you’re building and why, who you’re targeting in the market and why, how you’re going to grow and why, and how the end result will put your company into a better competitive position relative to alternatives. And why.

🌱 And now, byte on this if you have time 🧠

A technology often produces its best results just when it's ready to be replaced - it's the best it's ever been, but it's also the best it could ever be. There's no room for more optimisation - the technology has run its course and it's time for something new, and any further attempts at optimisation produce something that doesn't make much sense.

It’s a short read, but an interesting take on when something is about to become obsolete.

Read: The best is the last

And that’s everything for this week guys.

Thanks a lot for reading, and I hope you all have a wonderful weekend!

If you learned anything new, the best way to support this newsletter is to give this post a like or share. It helps other folks on Substack discover my writing, and gives me 🔋.

Until next time.

— Jaryd✌️