5-Bit Friday’s (#13): Snackable insights, frameworks, and ideas from the best in tech

On: The rise of the Natively Integrated Company, Counter-positioning, What Microsoft can teach us about breaching a moat, Making uncommon knowledge common, and 4 things Gen Z are thinking

Hi, I’m Jaryd. 👋 I write in-depth analyses on the growth of popular companies, including their early strategies, current tactics, and actionable business-building lessons we can learn from them.

Plus, every Friday I bring you summarized insights, frameworks, and ideas from the best entrepreneurs, writers, investors, product/growth experts, and operators.

Happy Friday, friends! 🍻

On Wednesday, I teamed up with Ali Abouelatta for an in-depth look at Canva (the $26b consumer design platform). If you haven’t got a chance to read it yet, there’re some great lessons on go-to-market motions, product-led growth, icebergs, and content strategy. You can bookmark it and catch up.

Today, we’ve got some super interesting stuff to cover…so let’s just get straight to it.

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

The rise of the Natively Integrated Company (NIC)

Counter-positioning as a business strategy

How Microsoft's attack on Google is a fascinating lesson on breaching a moat.

Making uncommon knowledge common → The power of data Content Loops in generating demand

What Gen Z thinks about work, college, and the internet, and how this will impact future business

The rise of the Natively Integrated Company (NIC)

While reading two different essays on Wander in the past 2 weeks (one by Packy McCormick and the other by Jacob Jolibois), the concept of a “natively integrated company” came up again and again. I wanted to learn more.

We all know AirBnB. And we all know how important hosts are to their business as listings by other people are what travelers are booking.

In other words — AirBnB aggregates supply for their customers.

The same model applies for most marketplaces you’re familiar with: Uber, Doordash, Amazon, Etsy.These aggregator companies bring in demand and match it with supply they don’t own. And this notion of not owning any supply has often been considered the holy grail of scale.

But, if you’ve ever stayed at an Airbnb, taken an Uber, or ordered from Doordash et al. — you’ve first hand experienced that quality is no guarantee. As Packy says perfectly, “Airbnb, and by extension, Airbnb’s customers, are dependent on the design aesthetics, standards of cleanliness, location, pricing choices, availability, and booking windows of its hosts. Airbnb can implement a rating system, highlight spaces that customers love to serve as examples, and ask users to turn on Smart Pricing, but since they don’t own their supply, they are ultimately unable to ensure the cohesiveness and quality of the customer experience across their ecosystem.”

That’s where a startup like Wander comes in, with their business model that counter-positions itself to an aggregator like Airbnb.

They do own supply, and it’s their own properties that are available for short-term rentals. And by owning supply and demand — they get to control every aspect of the customer experience from beginning to end, allowing them to provide consistently superior experiences. No relying on external suppliers to provide accurate photos of their listings, keep their car clean, or get your food delivered warm and on time.

This type of business model (natively integrated) is perfectly explained by Packy McCormick:

Power has moved from the companies who control supply to the companies who control demand, due in large part to the internet’s ability to connect companies directly to their customers.

The fastest-growing, most successful companies of the past twenty years didn’t produce anything physical at all. They connected their customers with other people who provide goods and services. Today, however, those companies are leveraging what they have learned from millions of customers to build their own supply in order to control their customers’ experience and their own economics.

Tomorrow’s best companies will be like a child who exhibits each of their parents’ and grandparents’ best attributes. They will be born with a focus on building products and experiences for customers whose problems they were born to solve. They will grow up in close contact with those customers, and their reputations will be built by how dirty they were willing to get their hands to serve them. They will have a digital native’s fluency with technology, and will wield it to smoothly connect the disparate functions necessary to deliver an excellent and personalized experience. In short, tomorrow’s best companies will be Natively Integrated Companies.

— Packy McCormick, The Rise of the Natively Integrated Company

In a series of 3 long-form essays, Packy goes deep into this type of strategy and looks at the shift from aggregator to natively integrated. For convenience, here’s a summary for you:

Act 1: From Linear Businesses to Aggregators and Back

Before the internet, the most successful consumer companies focused on owning the supply chain.

The internet flipped this equation. The biggest breakout successes created in the first two decades of the 2000s - the Aggregators - started by aggregating demand and using that demand to commodify supply.

Recently, Aggregators have been integrating backward and producing their own supply.

Standout quote:

If linear businesses are dead, and platform businesses [those who own connection, not production] are the future, then why are all the Aggregators suddenly building their own supply?

In a response to a critique of Aggregation Theory, Ben Thompson wrote “And sure, at some point the Aggregator may integrate backwards into distribution or supply, but the foundation of their power comes from aggregating demand, something that was not possible before the Internet.” I agree that these companies’ power comes from aggregating demand, but I also think that this is too dismissive a take on what is clearly becoming a trend: backward integration into supply.

What explains this trend? There are three main reasons that an Aggregator integrates backwards into supply: Data Advantages, Superior Customer Experience, and Better Economics.

And from here, aggregators that are backwardly integrating into supply can leverage their demand ownership, data advantage, and superior customer experiences to capture more of the profits in their value chain (via less margins to 3rd parties).

Act 2: Why There Won’t Be Any New Aggregators

Aggregators have snatched up the largest consumer spending categories, and their scale makes them hard to beat at their own game.

The window to build massively successful Aggregators via the internet in the US is closed — AKA no more Uber for X.

Aggregators won’t be disrupted by new aggregators

Standout quote:

Uber is everyone’s private driver. Airbnb invites its customers to belong anywhere. When you are the first mover in a huge space impacted by a paradigm shift, you can go wide and shallow.

[But] when the early spoils of a paradigm shift have been snatched up, you need to find your niche and go narrow and deep. You can’t win by running the same playbook as those who came before you.

Airbnb, Amazon, Zillow, Uber, Netflix and Spotify are the startup equivalent of early Twitter users: they have a massive head start (because they were first-ish), and the mechanisms in place to ensure their leads only grow over time. The next generation of successful companies will need to build their own followings by creating products and experiences that resonate with a passionate niche and grow from there.

Act 3: The Rise of the Natively Integrated Company

These factors set the stage for the rise of Natively Integrated Companies (NICs): companies that leverage technology to integrate the customer-impacting components of their value chain, build relationships with customers, and are willing to commit capital to build products that resonate with them.

Standout quote:

NICs start with the customer experience. To ensure continuously positive customer experiences, NICs build direct relationships with customers and iterate on product based on customer feedback. NICs work with agile third parties and have flexible operating principles, in order to execute on this customer feedback in a low-risk manner.

NICs combine the Aggregators’ direct relationship with customers and Linear Businesses’ supply chain and operational capabilities to deliver a delightful end-to-end experience.

As Keith Rabois put it on the North Star Podcast, in one of the most succinct arguments for NICs:

Customers don’t care whose fault it is when something doesn’t work perfectly. Customers care about the overall experience. And unless you control and can dictate the overall experience, you can’t optimize it. So the only way to create an awesome product is to dictate all the specs and all the component pieces. You’re always making compromises if you don’t fully integrate.

Now, I mentioned how Wander is counter-positioning itself to AirBnB. What exactly does that mean, though? 🤔

Counter-positioning as a business strategy

When a founder is pitching their new startup idea, whether to their mom to investors, a common question is, “What if [Insert big company] start doing that?”.

In other words, how are you going to build a business that won’t be squashed when/if an incumbent copies you? For example, in some hypothetical world where nobody is selling bananas yet, and you decide to open up a banana stand — the question is what will you do when the big grocery stores just adds them to their shelves.

And by and large, that’s a very fair question when you reflect on history. Even if a startup does find an excellent business model, there’s a very real and very high possibility that if it finds an noticeable success, Zuck may well copy and improve on it. Often, as we saw with Snapchat, out-competing it.

So, what’s the best way to think about answering this question of defensibility?

In our deep dive on Stripe, I wrote the following:

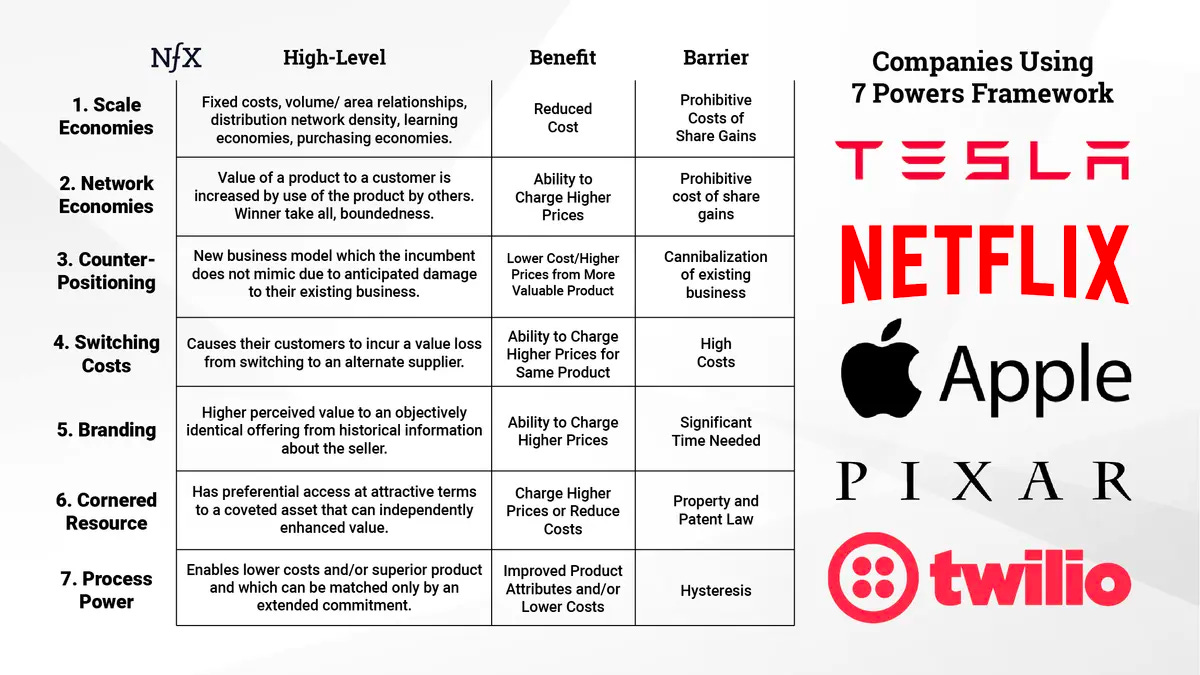

Another framework for thinking about moats [defensibility] comes from “7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy”, by Hamilton Helmer. The book argues that there are seven moats that a business can leverage to make itself “enduringly valuable.”

The book has a bunch of case studies that show us companies that use 1/2 of these moats to sustain their advantages.

Netflix takes advantage of (1) scale economies and (2) counter positioning.

Facebook and LinkedIn build (3) network effects.

Oracle has high (4) switching costs.

Tiffany’s has a powerful (5) brand.

Pixar’s “Brain Trust” is a (6) cornered resource.

Toyota’s Toyota Production System demonstrates (7) process power.

Stripe has all 7 of them 👀

To summarize that, here is a visual of this, by James Currier via NfX:

Now, going back to the question, “What if [Insert big company] start doing that?”.

A new startup isn’t going to make a strong case for beating Google on scale, network effects, branding, cornered resources, or process power. It could argue for switching costs. But it can definitely make a compelling case for counter-positioning.

Simply, because it’s a first-move that the startup can make against the incumbent that makes it very hard for them to copy without risking damaging/cannibalizing their existing business.

When a challenger goes to market with a strategy that uses counter-positioning, the incumbent essentially faces two questions:

Should we continue with the current business model, risking losing market share to the new entrant?

Or, should we adopt the new (possibly unproven) business model risking our existing business?

Obviously that’s over simplification, but it reflects the broad decision that needs to be made.

And the bigger the company, the more difficult change is. It requires a ton of resources and alignment, and along with it the clear risk of hurting the existing line of business that likely is raking in the cash. These factors often lead to delaying the decision to adopt the new business model, or trying it in a very limited way.

Some examples:

Wander vs AirBnB: They counter-position by owning the properties and controlling the end-to-end experience. Airbnb will win on variability of listings, but will struggle to win on quality and consistency.

Netflix vs Blockbuster: They counter-positioned through DVD by mail (instead of in-stores) and no late fees. Blockbuster was in a lock to copy, because (1) late fees were a significant line item, and (2) a core value of there’s was the in-store experience.

Robinhood vs big brokerages. They counter-position with zero fee trading. Big firms that make a shit load of cash on their commission are very reluctant to drop that.

Looking at those examples, the takeaway seems clear. A founder takes issue with the status quo and sets out to do the complete opposite — challenging the core value and/or economics behind the incumbent.

Now, there is a counter move/way of thinking available to the incumbent. Curious? 👀

And speaking of moats…

How Microsoft's attack on Google is a fascinating lesson on breaching a moat.

Earlier this week Microsoft launched Bing, again. Except this time, they’re positioning it as “your copilot for the web”, and it’s powered by their juiced up AI model for search.

Essentially, they’ve kicked the AI arms face in motion by brining together search, browsing and chat into one unified experience. As Casey Newton wrote earlier this week:

As I interviewed executives and watched presentations about the next generation of Bing on Tuesday, I was struck by the once-in-a-generation opportunity Microsoft may now have to shift consumer behavior. In December, running my first few queries on ChatGPT, I argued that the technology almost certainly represents the future of search.

Today, barely two months later, the future arrived in a browser on my desktop computer.

"It's a new day in search,” Satya Nadella told reporters as the day begun. “It's a new paradigm for search. Rapid innovation is going to come. The race starts today."

And Bing 2.0 is impressive. It’s like ChatGPT, except better trained to work in the context of search, always available (caveat, there’s a waitlist right now), uses real-time information vs being trained on a snapshot of data, and it links to different sources it uses.

Peter Yang (Product Lead at Roblox Ex-Reddit, Twitch, Meta) posted this on LI the other day about it:

Microsoft is going all in on AI with its "copilot for the web" vision. I watched their 55 min presentation and couldn't be more excited about the future of the web browser and search. Here are the top 5 AI use cases from Microsoft's announcement:

Summarize any webpage

You can use AI to summarize any webpage in a few bullet points directly from your web browser. e.g., Summarize Gap's earnings

Compare with another webpage

You can use AI to compare two webpages to get the main takeaways. e.g., "Compare GAP to Lululemon's earnings in a table:"

Rewrite code in a new language

You can copy and paste code from Stackoverflow and ask AI to rewrite it in another language. e.g., "Rewrite this Python code in Rust:"

Plan trips

You can ask AI to make an iternary of a trip and then summarize it in a casual email for family members. e.g., "Plan a 5 day trip to Mexico City:"

Generate social content

You can give AI an 1-line prompt and then pick the tone and format to generate a full social post. e.g., See the pic below for an example for the LinkedIn influencer in all of us.

The implications for search are clear but I think building this into the browser has even more impact. Why navigate to Google search when you can talk to your browser directly to get better answers?

And that last point brings us to Microsoft vs Google. Google has 96% search dominance on mobile (85% on desktop) — and it’s their core product and revenue driver.

Microsoft releasing the next generation of search before Google is an act of war (hence why Larry and Sergey returned for this code red).

Sushant Koshy (Senior Product Manager at Atlassian) captured what Microsoft is doing here really well yesterday.

Microsoft's attack on Google is a fascinating lesson on breaching a moat.

1. Microsoft is attacking multiple products. Google Search, Chrome, and Google Suite. All at once!

2. Microsoft is attacking financially. Nadella said “From now on, [gross margin] of search is going to drop forever”

3. Microsoft is controlling the narrative. Microsoft is making a lot of noise about its advances in AI and naming Google explicitly (which is rare). In markets (especially capital markets) perception is crucial. Microsoft is winning the perception battle.

4. Google overestimated its ability to protect its moat. Google always knew Artificial Intelligence was their moat. But they underestimated competitors.

They probably assumed that big tech (Microsoft, Apple) won't be nimble enough to compete and startups won't have capital. They didn't foresee an OpenAI + MSFT combo.

5. Google's revenue is not diversified, making it vulnerable. ~57% of revenue comes from Search. With such concentration, they have no option but to respond dramatically to this Microsoft Bing move.

Such fast reactions are laden with errors, like the demo video fiasco that happened recently.

6. Microsoft persisted for years. Never write off anyone. Bing and Internet Explorer were the butts of numerous jokes over decades. Microsoft persisted in these markets and grabbed on the opportunity when it presented itself. Of course, it needed a legendary leader like Satya Nadella to pull this off.

In response, Google pre-announced its own conversational AI tool Bard on Monday. Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai said Bard would be available “in the coming weeks.”

If we expect that Bing and Bard will be broadly comparable, as screenshots of the latter product suggest they will be, then Microsoft’s first-mover advantage here might not last through February.

But the unprecedented growth of ChatGPT suggests that even a few weeks might give Microsoft an enduring head start — or at least enough runway to begin chipping away at Google’s search dominance. Peeling off even 1 percent of Google’s market share would be worth $2 billion a year in advertising revenue to the company, executives told investors on a call Tuesday afternoon.

In short, the presentation did not go well. Google’s stock dropped, wiping out $100b in value.

ChatGPT came out a little over 2 months ago, and we’re already here. Things are moving fast, and if nothing else, this whole AI race is getting very interesting. Speaking of, if you missed our deep dive on OpenAI (one of the most popular ones yet), don’t miss it! 👇

Making uncommon knowledge common → The power of data Content Loops in generating demand

If you’re in the US, you’ve no doubt heard of Expedia, Zillow, and Glassdoor. If I was a betting man, I’d say you’ve used all three.

And while placing my bets, I’d add that you’ve never heard of Rich Barton. Neither have I.

Well, he’s the guy who founded 3 multi-billion dollar consumer companies, and has found a playbook for repeated success.

There’s an excellent essay by Kevin Kwok where he unpacks a fundamental part of it — making uncommon knowledge common, and driving demand using data content loops.

I’ll let Kevin explain:

Repeatable success is key, especially in Consumer tech which is one of the hardest areas to succeed in. […] The playbooks are far less developed—and no one’s playbook has demonstrated the repeatability of Rich Barton’s.

To reliably successfully invest in consumer is a rare feat; to repeatedly found successful companies is virtually unheard of. Doing so suggests a founder has hit upon an underlying structural playbook that isn’t yet commonly known, or successfully replicated. And while some of Rich Barton’s techniques are commonly understood, his core strategy to catalyze his compounding loops is not.

So What’s the Playbook?

If you’re reading this, you’ve likely used Zillow, Glassdoor, and Expedia before. It’s hard to look on the internet for anything related to real estate, jobs, or travel and NOT see one of Rich Barton’s companies. Their ubiquity is stunning.

But it’s not coincidental.

Rich Barton’s companies all became household names by following a common playbook.

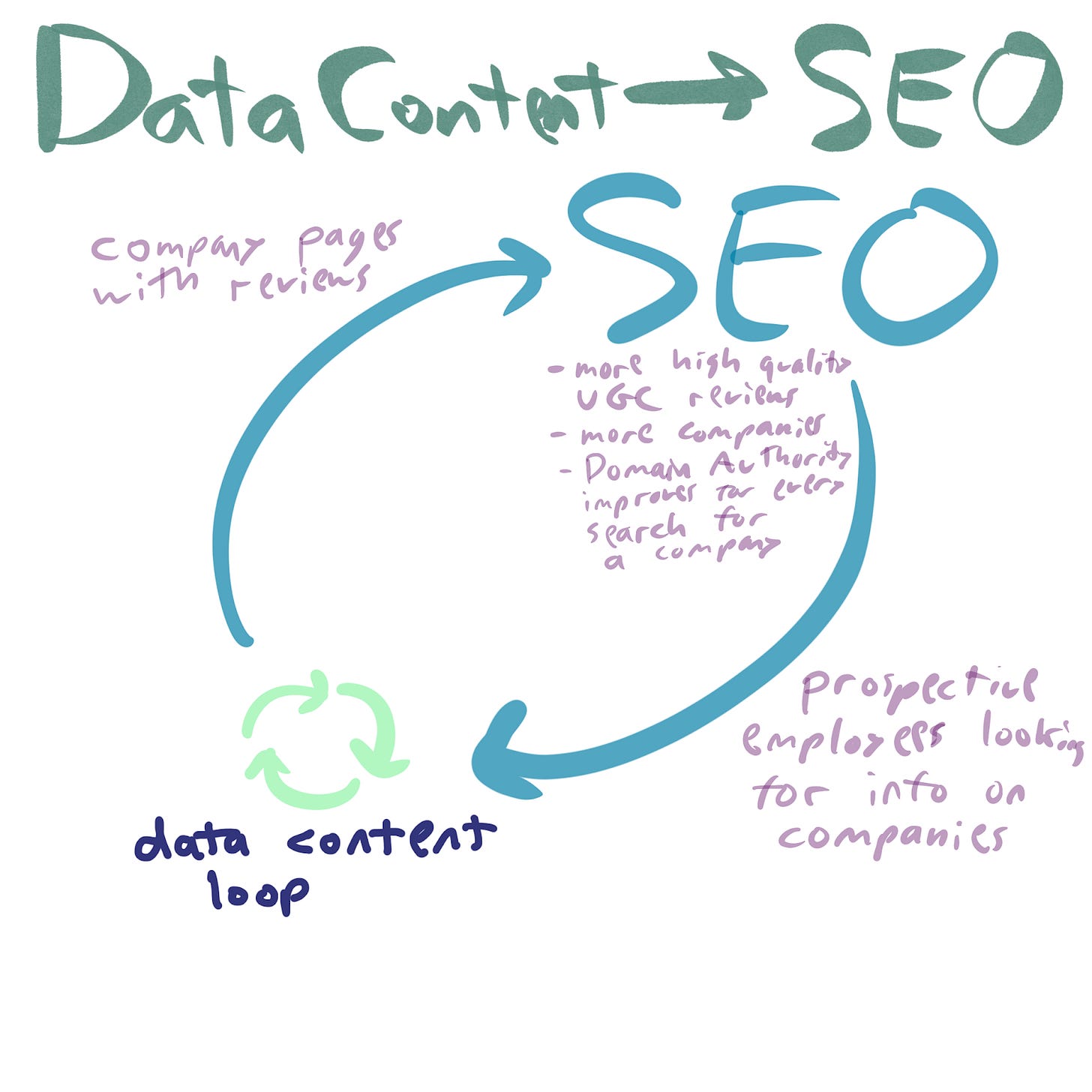

The Rich Barton Playbook is building Data Content Loops to disintermediate incumbents and dominate Search. And then using this traction to own demand in their industries.

Or as he puts it “Power to the People”

Much of what Rich Barton pioneered has now become mainstream. SEO/search is well saturated, and the importance of owning demand has been popularized by Ben Thompson’s many essays on (Demand) Aggregation Theory. But the cornerstone of Rich Barton’s playbook, Data Content Loops, are still underappreciated and rarely used.

Owning demand gives companies a compounding advantage, but needs to be bootstrapped. When a company is just starting out, it not only doesn’t own demand, it has all the disadvantages of competing against others that do.

In order to grow their demand high enough to become a beneficial flywheel, Barton’s companies use a Data Content Loop to bootstrap their demand and create unique content and index an industry online (homes for Zillow, hotels and flights for Expedia, companies for Glassdoor).

Expedia: Prices for flights and hotels that before you’d have to get from travel agent

Zillow: Zestimate of what your house is likely worth that before you’d have to get from broker

Glassdoor: Reviews from employees about what a company is like that before you’d have to get from a recruiter or the company itself

These Data Content Loops help the companies reach the scale where other loops like SEO, brand, and network effects can kick in.

Barton’s companies then use this content to own search for their market. This gives them a durable and strong source of free user acquisition, which enables them to own demand.

To visualize:

A key part of building a consumer business is getting that critical initial demand. And as Rich Barton has shown us — data content loops are a great strategy because they empower consumers.

You can dig deeper on this is Kevin’s full essay, linked below.

⛏️ Source + dig deeper: Making Uncommon Knowledge Common, Kevin Kwok

And to close us out this week…

What Gen Z thinks about work, college, and the internet, and how this will impact future business

I very recently came across the work of Rex Woodbury. He’s a partner at Index Ventures, and also writes the Digital Native newsletter, where he looks at how people and technology intersect. What a great niche.

Rex has some fascinating pieces, and today, I bring you some of his research on Gen Z.

Why should we care? Well…

I’ve explored Gen Z in depth before: last summer’s Minions and Gen Z Characteristics was one of my longer pieces, delving into 10 specific characteristics of the up-and-coming generation. In that piece I wrote, “When you account for the fact that Gen Z is now the largest generation in the U.S., small-scale behavior changes compound into macro-sized cultural shifts.”

This is why studying young people matters. Gen Z (roughly anyone born between 1997 and 2012) is two billion strong globally. In tech, we often talk about “platform shifts” and new technologies (blockchain! AI! cloud!), when new behaviors, attitudes, and worldviews just as often inform which companies break through. (To be fair, it’s usually a combination of the two.) If I think back 15 years, the Millennial coming-of-age powered companies ranging from Instagram to YouTube, Robinhood to Airbnb. The question is: what companies born today will ride the wave of Gen Z?

— Rex Woodbury, via Digital Native

In his essay, What Gen Z Thinks About Work, College, and the Internet, he talks about 5 trends. And as we look at them, it’s very clear how they will have an impact on future companies and what they build. Let’s take a look (I’ve dropped my favorite excerpt from each).

“I kind of wish phones didn’t exist.”

Gen Z is nostalgic. [And] brands are taking advantage, of course. Coach built a vintage drive-in theater for its runway show last year; Old Spice, not to be outdone, launched a traditional barber shop harking back to the 1950s. You can’t blame them: #nostalgia has 66.1 billion views on TikTok.

And it’s not just Gen Zs: Millennials are also nostalgic, and the 90s are as much in vogue as the naughts. But my view is that Gen Z is nostalgic for a very specific reason: this is a generation that has never known a world pre-internet. The iPhone turned 15 last summer, meaning that today’s high schoolers don’t remember a time without it. As a result, this generation has mixed feelings about their tech-dependence.

This shows up in interesting ways. One fascinating phenomenon is the embrace of analog technologies.

“I met most of my best friends online.”

While Millennials were trained to be individualistic, I’ve found that Gen Zs are much more focused on the collective. I wrote about this a few years ago in Digital Kinship, arguing that belonging was replacing status as the core human need online. Many young people don’t care about performing for others with airbrushed photos and curated grids; instead, they just want to be part of a community.

The solution for young people is finding community online. This has given rise to interesting phenomena: the act of watching people play video games; mukbangs, livestreams of a creator eating; even sleep streaming, the act of watching people sleep.

“I don’t have a dream job because I don’t dream of labor.”

This quote has become something of a Gen Z rallying cry. I see it and hear it often, and it perfectly captures a younger generation’s wry, borderline-nihilistic attitude.

It also captures broader trends—blowbacks against capitalism, against institutions, against work itself. We see flavors of this in the rise of the subreddit r/antiwork, now 2.4 million members strong (members call themselves “Idlers”), a 185x multiple on the 13,000 members in 2019. We see flavors in the much-hyped “quiet quitting” phenomenon of late 2022.

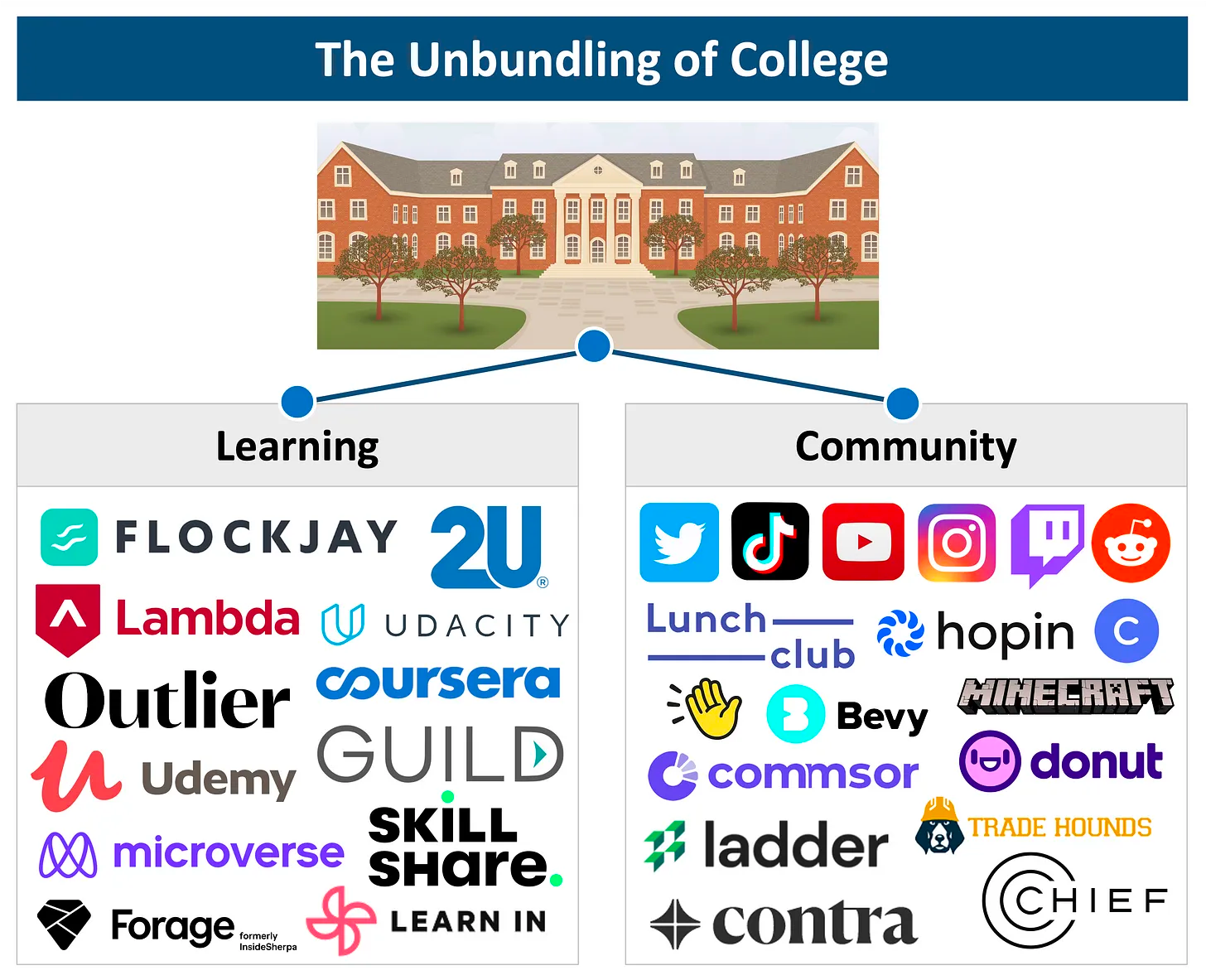

“Half my friends have no intention of going to college.”

A January 2022 survey from the ECMC Group found that only 51% of Gen Zs want to pursue a four-year college, down from 71% just two years ago. Meanwhile, 56% believe that a skills-based education makes more sense in today’s world.

The cost of education is growing 8x faster than real wages. In the 1950s, 30% of household income was enough to pay for college. Today, people need to shell out 80% of their household income. Two-year colleges and vocational schools look like better options.

In 2021, I wrote about the unbundling of college—how we’re seeing a cleaving of college into “learning” and “community.” Much of college has historically been about “the college experience”—the Animal House-esque rite of passage for adolescents. I’ve always liked how Ian Bogost once referred to America’s perception of higher education: “A safe cocoon that facilitates debauchery and self-discovery, out of which an adult emerges.”

Yet with college becoming prohibitively expensive, young people will need to seek both learning and community elsewhere.

As Rex says well, there’s a gap in life when it’s difficult to keep your pulse on a younger generation. This gap comes when you’re not so young anymore yourself, and you don’t have your own kids to observe. So, as builders, I find his insights here some good food for thought. 🙏

And that’s it folks…some great insights there from some brilliant thinkers. If you enjoyed todays post, I’d love it if you shared HTG with a friend or two.

If this was your first time reading and you want to keep getting these roundups each week (plus our deep dives), you know what to do. 👇

Otherwise, have a fantastic weekend, and I’ll see you next week.

— Jaryd ✌️