Why WeWork Died: Lessons from the plight of a $47B t̶e̶c̶h̶ ̶s̶t̶a̶r̶t̶u̶p̶ landlord

Fugazis, hubristic leadership, legal theft, over expansion, zealots vs pragmatists, and more.

👋 Welcome to another edition of Why They Died. Your occasional trip to the startup graveyard, where we investigate what caused once high-flying companies to fail.

To learn from the failures & successes of others, drop your email and join 13K+ others:

Hi, friends 🧟

At its peak, WeWork was once the most valuable startup in America. With top-tier backing from the likes of SoftBank, Benchmark and JPMorgan Chase, WeWork was running around Silicon Valley with a $47B price tag and the investors to boot.

But, on November 6th, just 4 years later, the company that built a real estate business around lease arbitrage failed—filing for bankruptcy.

The story of this make-believe tech startup is well covered. And typically if you have Jared Leto and Anne Hathaway staring in your Apple TV show, you’d expect the failure to be total and swift. Like with SBF and his story of bringing FTX, the second biggest crypto exchange in the world, to dust overnight. Or Bernie Madoff. Or Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos. All these examples bring us tales of charlatan founders who eroded something “valuable” at breakneck speed, sending their companies into death spirals.

While WeWork’s founder/CEO Adam Neumann was deeply problematic, and in my opinion, a root cause problem, the story of WeWork—despite Leto portraying him in Apple’s WeCrashed—is a different tale. Perhaps that’s because Adam’s fraudulence wasn’t the kind that has the DOJ or FBI cuffing you. Rather, it’s the more subtle kind. The kind hidden behind the smoke and mirrors of being “a visionary” and having a level of charisma that allowed him to convince some very rich and smart people to let him light their money on fire—making him incredible rich while, excuse my French, fucking over everybody else.

And part of that ability to convince investors to rally behind his vision of “elevating the worlds’ consciousness” (yuck)— a farfetched rhetoric about their ability to change the world even in startup-land standards— is that WeWork was a product of a boom, and during booms and times of frenzy, investors ignore all the red flags and do stupid things.

WeWork was a short-term landlord trying to make a buck on the delta between the cheaper long-term leases they paid, and the more pricy short term leases they charged. But, they masqueraded as a tech startup and commanded ludicrous multiples because, basically, they had a cool app to book spaces and used some analytics.

They’re not the only example of regular businesses who played dress up as a startup and paraded down the valley for Halloween. Greensill Capital claimed to be a FinTech disruptor, but were really just a glorified lending shop. Peloton, the “tech company that merges the physical and digital worlds”, is really just a spin bike with live-streamed videos.

To be clear, I’m not shitting on those business models, but I am saying they should not be seen/valued as actual startups who have things like solid margins, affordable scalability thanks to growth loops and network effects, etc.

Investments in these type of mislabeled products have cost funds billions.

Of course, being overvalued isn’t why they failed. In today’s startup business autopsy, we’ll unpack some of the big drivers that led to WeWork’s tumble from $47B down to $97M. 🤭

Sometimes the best lessons come from studying what not to do. So, let today’s post, the 4th installment in our failure series, be a summary of an exceptionally expensive lesson. One paid for mostly by SoftBank.

Shall WeBegin?

⚠️ p.s As always, my posts get cropped in emails. To read the full thing and not have your experience cut short (like WeWork did), click here for the full post.

Drive engagement. Close deals.

If you’ve ever tried building a product tour for your product before, then you know that doing it natively is not only time-consuming to build, but a real pain to maintain.

If you haven’t explored demos yet and you operate a SaaS app, they are an excellent onboarding tool to help your users activate, engage, and ultimately retain. I’ve had huge success in the past with guided demos as a way to drive adoption.

That’s where Storylane comes in. They help you build killer product demos in just a few minutes.

This has helped customers like Twilio and Gong see 25% increases in pipeline, 2X more platform engagement, and 30%+ in sales velocity.

AKA, Storylane helps you bring in more leads who use the product and then become customers.

With Storylane, you can leverage the power of interactive and personalized demos to shorten your sales cycles, increase prospect interactions, and convert more visitors. Storylane also gives you actionable data on demo engagement and gives you an AI assistant to help you figure out which demos are driving qualified leads.

To start boosting your product-led growth and getting more customers, join other tier-1 GTM teams by checking out Storylane.

Want to learn more about sponsoring this newsletter? Advertising opportunities

WeClimbed: The startup delusion

We won’t spend too long here—the rise of WeWork is well covered. But, incase you’re not up to speed, here’s a quick primer: Their rise is a story of tech-bro mysticism, intense hours, overpromises along with detached-from-reality dreams, and Don Julio tequila mixed with sexual harassment.

Founded in 2010 by Adam Neumann and his wife Rebekah, WeWork’s goal was to “revolutionize” the office market by popularizing co-working.

The co-working model suits building owners very well. Landlords don’t need to go fill their buildings or floors with a handful of large tenants with long leases. Instead, landlords master lease their buildings and floors at a wholesale price to a co-working operator like WeWork. With some renovations, these operators can fit more people into spaces than conventional tenants, and because of their readymade interiors and flexible terms, they can charge higher rates than large tenants on a square foot basis. The WeWork’s of the world make/made money on the difference between their wholesale master lease price and the combined membership rent roll.

Basic arbitrage. But thanks to some trendy office upgrades with Kombucha on tap and a compelling founder, it was seen as a disruptor with a business model unhindered by property ownership.

Somehow, Adam— the barefoot Israeli Navy veteran known for his signature look of long unkempt hair, taste for Don Julio, expensive tech-bro partying, and obscure hippie wisdom—made people see something that wasn’t there.

But, in part, that was the world we were living in circa 2010. We were in a bubble, and that led people push aside critical thinking and logic in light of making big bucks on some new upshot.

WeWork was founded in the middle of the recession of 2008–2012, which is critical to understanding their growth and eventual collapse. The Fed’s strategy for reinvigorating the U.S. economy during the recession was to purchase and resell billions of dollars worth of distressed real estate, thereby saving banks from mass defaults on the dodgy loans those banks issued. The Fed also lowered interest rates to encourage investment and development in existing and new real estate — rates that remained low until early 2022. While rates were low, post-subprime lending criteria became stringent, so the main beneficiaries of the low rates were wealthy individuals and institutional borrowers, many of whom converted the loans into high yield real estate investment products like build-for-rent single family housing. It was during this period that real estate investment trusts (REIT) like Blackrock started to multiply.

One of the chief repositories for these low interest loans were the glass-clad commercial and multifamily high rises that dominate most urban vistas today. But there was a problem with these buildings: in their haste to gobble up cheap loans and attendant development fees, developers and investors weren’t entirely clear who’d be the tenants of these buildings.

This is where WeWork came in, promising to solve the problem by gobbling up space. And they did, very quickly. This then fed into Adams’ narrative of WeWork being the hot new thing—the co-working company that controlled supply, without owning it.

When WeWork launched, Silicon Valley was high on the rise of the sharing economy, powered by the exciting idea of being asset light on traditionally asset heavy businesses. The classic “The biggest taxi company (Uber) owns no cars!”, and “The biggest hotel (Airbnb) owns now property!” hyped up the idea of what WeWork positioned itself to be—the biggest office block that owned no property.

This all allowed them to expand at an insane speed, which increased revenue but also racked up steep losses. Sure, they didn’t “own” the buildings, but they signed 15 years leases, which is the next worst thing. Each lease = a liability. And those liabilities ate away at any shot at a profit.

Simply, WeWork grew, ironically, by digging itself into a bigger and bigger hole.

But that hole wasn’t so apparent at first. From 2012 up until COVID, office demand was high. This masked the problem enough. The same low interest rates that led to more square footage being built also resulted in the growth of finance, tech, and other commercial sectors, most of whom still saw offices as necessary tools for work. This demand later proved temporary, since it depended on access to historically low rates rather than functional needs.

While Adam was a bullshit artist, he wasn’t entirely wrong about the future of work. Collaboration tools were permitting the proliferation of more, smaller, nimbler organizations. Membership benefits like beer-on-tap and pizza Friday’s were a fit for the growing cultural zeitgeist for having a life outside of offices and working. And community is extremely powerful.

But, what WeWork was wildly wrong about was market size and demand. This led them down a path of creating as many spaces as building inventory permitted. Supply quickly outgrew demand. As the debt kept flowing and building inventory increased, so too did WeWork’s leases. By 2018, WeWork was the largest office tenant in New York City.

And unlike Uber and Airbnb, when demand decreased and revenue shot down, WeWork wasn’t able to scale down their supply in response. They were locked in and obligated to cough up.

A nice segue into the reasons behind their failure. 👇

WeCrashed: Lessons from the reckoning

Things went to shit for WeWork in 2019.

It’s not that that’s when their problems started, rather, it was when everybody saw them.

It was August 14, 2019, and WeWork had just filed Form S-1 to go public at a $47B valuation. In short, the filing revealed crazy losses despite growing revenue, expensive lease agreements and long term obligations, and an at best “complex” relationship with founder Adam Neumann.

Almost immediately, WeWork was in the dog box. Investors, analysts, and journalists had a field day with their 359 page doc, and headlines swarmed the internet calling WeWork, and Adam, out for their many issues.

Triton Research's Rett Wallace would later call the prospectus a "masterpiece of obfuscation", and Scott Galloway wrote a takedown of the company titled "WeWTF.”

It truly was a reckoning, where at last pundits were calling WeWork on their shit. Something their investors seemingly were incapable doing. In just a month, they canned the idea of going public for a while, and their valuation took a nose dive of more than 70%. Adam who had high hopes of being the first person to enter the 4 comma club, was given the boot as CEO (an ousting made easier with a $445M exit package). As Dakin Campbell wrote for Business Insider.

Two things had changed in the nine years since Neumann began constructing the myth of WeWork with the help of starry-eyed tech journalists and hungry investors: Theranos and Uber. In the fall of Theranos, the blood-testing company that imploded under accusations of fraud, the investing public saw how a multibillion-dollar valuation could be spun up from Silicon Valley bromides and the image of an idiosyncratic, enigmatic founder who inspired cult-like devotion. In Uber, whose stock has trended downward since it went public, they saw how machismo, hubris, and accounting tricks could obscure fundamental business challenges.

Unfortunately for Neumann, it was precisely the wrong time to be the visionary leader of a company with imperial dreams and obscure finances. Patience had run out.

Post Adam’s departure, the company went through various rounds of executive leadership changeovers. WeLive and WeGrow were shut down, and The We Company went back to WeWork. Then in October 21, 2021, they went public.

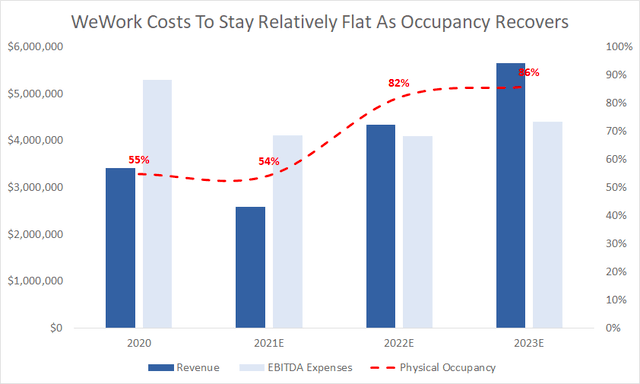

So, let’s unpack the biggest reasons behind this sad chart. Reasons that started long before their IPO, and reasons outside of the obvious pandemic that shook up their business.

There are three main ones:

Unsustainable business model: Don’t buy what you can’t afford

Overvaluation and rapid expansion: A vision misaligned with reality

Hubristic and dishonest leadership: Failure to switch from a zealot to a pragmatist

Let’s run through each and see how we can avoid similar mishaps.

1. Unsustainable business model: Don’t buy what you can’t afford

A huge underlying issue was WeWork’s over-reliance on long-term leases with short-term subleases.

It’s very easy to see how this is a problem. Hypothetically…

WeWork pay the building master lease rent of $10M/year

WeWork require 70% occupancy in said building to cover lease obligation

But if they have, say, 60% occupancy…shame, tough cookies. WeWork is committed to paying for 15 years regardless, and WeWork’s whole pitch to their tenants is that they can cancel easily. It’s very easy for them to be underwater.

AKA, they’re extremely exposed to the short-term fluctuations in demand for office space and need strong occupancy levels to just break even. This isn’t just something that was obviously impacted by Covid, but also just the general fact that most leases in WeWork were for ~2 years. So, naturally, their clients were short term and WeWork always needed to be filling those desks with new people.

And being anywhere below break even is insanely costly…we’re talking big buildings takeovers in some of the most coveted and expensive cities in the world. Their operational costs outside of the lease were also wild. The bills piled up quickly. Like, $219,000 an hour quickly.

In a sense, they made the classic mistake that brought down Lehman Brothers and more recently Silicon Valley Bank: their sources of capital could flee before their financial obligations came due.

At one point, they were on the hook for $47 billion in future lease payments to building owners while having committed revenue of just $4 billion. And while Adam always pitched WeWork in the context of the Airbnbs and the Ubers of the world—the scale ups that owned no assets and promised great returns on capital—and commanded a similar type of valuation for it, so obviously that was total crap. 🤦♂️

The whole idea of “the sharing economy” and not owning assets is simple: those startups use other people’s assets which makes the company more resilient since they can scale down as inexpensively and fast, during bad times, as they scaled up.

But WeWork didn’t really use other peoples assets. Sure, they didn’t own the buildings, but they mind as well have been the owner with long-term financing that gave them responsibly for these massively expensive assets. WeWork could not just scale down their buildings without breaking their terms with owners.

So, WeWork was very much asset/capital heavy. And after reading this piece by Reuters, it seems they were able to hide behind some smoke and mirrors thanks to “creative” accounting. As Steve Clayton, Head of Equity funds at Hargreaves Lansdown said, "Innovative financial metrics are rarely truly innovative, instead being a way of disguising a lack of cash profits, and WeWork played that game for all it was worth."

From here, they grappled with expensive leases and clients cancelling agreements as vast numbers of people started to work from home after the pandemic. As much as they tried to amend their leases and restructure their debts, it just wasn’t enough to fend off bankruptcy.

But, this problematic business model is something that could have been managed IMO if it wasn’t for a vision misaligned with reality, leading to an aggressive expansion strategy.

How to avoid this 🛠️

Rigorously evaluate the risks inherent in your business models, and make sure you they are not overly reliant on high-risk strategies, especially those that involve significant financial commitments or uncertain revenue streams.

Always know what your true operating costs are (the obvious and the phantom ones), and have an honest assessment of things like CAC, payback period, LTV, and at what point you’re going to be turning a profit. It’s not okay to say “We’ll figure our the $ money later…it’s fine, that’s what Facebook did and look at them now!”. Those days are gone, and you need to have a clear business model that allows you to grow in a healthy way.

Oh, and if you enjoy sleep, don’t buy what you can’t afford.

But, for just $7/m, you might be able to afford upgrading to paid. Why? 👇

2. Overvaluation and rapid expansion: A vision misaligned with reality

In the the glut of post-2008 debt, where investors were looking for any semi-plausible place to invest their money, WeWork became a symbol of Silicon Valley's boundless audacity and self-professed exemption from the laws of economics.

Some say—like I have already a few times—that investors should have seen the writing on the wall. The insane financial obligations and the burn rate paint a clear picture of an asset heavy company with an unsustainable business model. But, again, people do silly things and miss the signs during booms.

So call it rose-colored glasses x Adam’s hubristic leadership combo—but here’s the bottom line: WeWork is a textbook example of how a misjudgment of market demand and competition can lead to an inflated valuation, leading to unrealistic growth expectations, leading to aggressive expansion without proven profitability models.

With their plans to transform “human consciousness” with flexible working spaces and more all around the world, Adam’s ego set them on a path of relentless expansion. This shotgun approach led them to acquiring far too many master leases, which not only racked up their liabilities, but also led them to overlook the importance of understanding local dynamics, cultural nuances, and varying demands. This led WeWork to simply have too many spaces available in any given market, in turn, resulting in unoccupied desks and strained resources.

And that’s an important lesson worth repeating for operators: success in one market/location is by no means a guarantee for success everywhere. A one-size-fits-all approach is, by and large, fundamentally flawed especially in an industry where location is crucial.

This all led to exorbitant costs, requiring WeWork to keep raising money to (1) pay their bills, and (2) keep expanding with more leases. And with more raises came higher and higher valuations that were increasingly drifting further away from WeWork’s somber financial reality.

By 2019, Softbank had already pumped $18.5B into Adam’s dream. And billions more were raised from institutional investors like Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and real estate giants like Brookfield and Cushman & Wakefield which allowed them to sign more and more leases, giving them the impression of legitimate market demand and revenue growth. Adam played into this impression, using the personal money he siphoned from investment rounds to invest in buildings that he leased to WeWork.

The whole Fugazi was built on the assumption of perpetual growth, and ignored the important variable of market fluctuations and economic downturns—which of course came.

As Warren Buffet famously said, “Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.” And the demand did indeed pull back, and only then did investors start to see how exposed they really were.

Speaking of investors…

As Matt Levine pointed out, at the peak valuation, WeWork was worth almost half the entire value of publicly traded US real estate investment trusts: “Nobody gets into venture capital because the best-case scenario is doubling their money. For WeWork, maximal office-landlording success would be kind of disappointing”. The returns would just not be juicy enough.

Thus, to keep raising more cash and painting a pretty picture of the 100X ROI VCs look for, more ambitious schemes were required to flavor up the story.

Overdiversification and the subsequent loss of focus on the core business

WeWork’s shtick to show how such an ROI was possible was to show that WeWork was so much more than a short-term leasing play.

This is where “The We Company” was created, the parent organization for what was to be a suite of products that “elevated human consciousness”. WeWork was just part of it. Two big diversifications away from the core were a company that included micro-apartments (WeLive), as well as WeWork-style and elementary schools (WeGrow).

In part, WeWork needed to do this because they needed to keep raising, but it was also the overcapitalization that permitted ambitious side businesses like this in the first place. WeLive was a failed attempt at translating their office strategy to residential living. Same idea as WeWork, except with one big oversight: residential space conversions are way more expensive and regulated than office spaces.

This obviously went nowhere—I think just 2 buildings were opened and then closed.

Outside of creating new businesses before turning a profit with their main one, WeWork also made a ton of investments and acquisitions. For example, like their $13 million investment in a wave pool company. Or they soiree into gyms and coding camps.

Like, what is your product guys??

And the more they made investments elsewhere, the faster they burned through capital and lost focus on actually growing the core product in a sustainable way. All that money could have been invested in fixing the bread and butter business model. Plus, that was of course all made far worse by the fact that they couldn’t deliver on any of new ideas effectively—throwing even more fuel on the dumpster fire and at the same time hurting their “We” brand reputation.

How to avoid this 🛠️

Always balance the need for expansion and growth with the realities of your operational capabilities and market conditions. This means avoiding overcommitment to long-term expenses without a reliable and stable revenue stream. You never want to be spread too thin, especially without a cash cow to fall back on.

And when you do expand, push into categories that are clearly adjacent—categories where you have clear advantages from your core product. Those could be expertise, data, relationships, distribution advantages, economies of scale, or any other advantage that can help you win. It’s not about investing and building in areas that you think are cool (Adam…), but areas where it makes sense for you to go for long-term success.

Expansion (M&A or R&D) should always be viewed in a 1+1=3 fashion.

3. Hubristic and dishonest leadership: Failure to switch from a zealot to a pragmatist.

In a sense, all of the above boils down to a root cause problem: Adam Neaumann.

Adam oversold the dream to investors. Adam charmed their checkbooks. Adam drove the decision to take on too many leases. Adam invested the capital unwisely. Adam always put himself and his pockets before that of WeWork.

And while most companies are structured to have checks and balances, the WeWork structure was confusing and protected Adam and his family to a large degree. Corporate governance was less than an afterthought.

Adam had near total control as it was outlined in their IPO prospectus. WeWork would have three classes of stock, including two that awarded him 20 votes for each share. If he died, his wife would have the power to name a new CEO, independently of the board— Game of Thrones style.

While he was still there, his board supremacy allowed him to enact a number of sketchy financial practices that were obviously a conflict of interest.

Looking back to FTX and Theranos, like WeWork, all of these companies could have been interesting (and perhaps still around) if they had the right leaderships—honest leadership—and actual systems in place.

While Adam isn’t a criminal like SBF and Holmes, he made some very poor decisions at the top. While the company was hemorrhaging money, he was living it up and lining his own pockets. He was cashing out stock options, taking out loans from WeWork at essentially 0 interest, buying over 10 of his own buildings and renting them to WeWork at a premium, buying the IP for the “WE” name and charging WeWork millions to use it, flying the jet wherever he wanted, and generally just behaving like the company was his personal piggy bank.

Some say that Adam was simply in over his head. He was a young CEO, and he didn't have the experience to navigate a company through tough times. Others say that Adam was well aware of the problems at WeWork, but he was more concerned with making money than with running a successful business.

I’m unequivocally in the latter camp. I think Adam is an incredibly smart guy. He knew exactly what was up—he saw the opportunity in 2010 and identified WeWork as a vehicle that could make him a billionaire. And he pulled it off in a way that skirted on the lines of what could actually get him in trouble. He played the game, and truthfully, he won it.

Despite his stock now being worthless, he got paid hundreds of millions in cash. He’s a very well off man. He’s not in jail. He’s not being investigated. And while his reputation has taken a knock, seemingly it ain’t so bad: he’s raised $350M already from a16z for his new real estate company Flow…another one with a tech valuation….focusing on community. Um, what? 🤷♂️

You can’t make this shit up.

A zealot for the village, a pragmatist for the state

Scott Galloway wrote a piece about Adam and WeWork, and he does an excellent job at describing an important transition that startups need to go through to find long-term success. He writes:

Founding a business that achieves any level of success requires ambition, talent, an irrational belief that “this” makes sense, and most important the ability to attract a flock of investors who consent to engage in your hallucination. The best founders are Zealots.

Zealots are high-talent, high-energy people — but they also tend to be narcissistic and divisive assholes. If you’re thinking “Takes one to know one,” trust your instincts. Zealots make good founders, but as companies mature, the ratio of their passion relative to the cost incurred by their difficult personalities erodes. Maturity calls for sober leaders who are better at managing risk and serving the market’s desire for predictable, if not remarkable, growth: Pragmatists.

He then adds:

Uber and WeWork had the blessing/curse to be founded by Zealots, men so irrationally committed to their vision that they ignored naysayers, business issues, laws, ethics, and math. Though, to date, a disregard for laws or morality has been a feature not a bug across the innovation economy. Math proves to be the arbiter of who survives/thrives. WeWork was the ultimate expression of a Zealot-founded company, exhibiting hypergrowth, a proliferation of side projects, and a company culture based on a cult of personality bordering on a (wait for it) cult. Founder Adam Neumann inspired devotion and elicited hard work from his team, but he created a workplace that felt more like a movie of the week than a public company. It likely could have survived this, as Uber did, but profligate spending ($60 million Gulfstream G650) and self-dealing transactions — (personally licensing the “We” brand to the company for $5.9 million) triggered the market’s gag reflex.

Neumann’s flaws were evident to insiders long before the company’s 2019 aborted IPO afforded investors a peek inside the circus tent and required the board to finally address the Neumann issue. However, it swapped in one Zealot for another — in this case business history’s greatest enabler: SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son. The Japanese billionaire was the largest backer of WeWork, having invested $6.4 billion by the time of the failed IPO, and he’d once told Neumann he needed to be “crazier.” Masa doubled down on his investment (literally, with a $9.5 billion “rescue package”) and took over the company himself.

A decent definition of “crazy” is doing the same thing while expecting a different outcome. So Son followed his own advice and became fucking insane, shoveling good money after bad. After a legal fight with Neumann, and the world’s largest blink by Masa (paying Neumann a billion for his shares), there was a SPAC, and more hemorrhaging of capital.

Adam was clearly a zealot. And that can work during what Reid Hoffman calls “the town and the village stages” of company building. But, when you transition to the “city and state stages”, either the founding CEOs need to evolve into pragmatists, or they need to hand the keys over to someone who is.

But, unlike Uber who exiled Travis in favor of Dara (the pragmatist) WeWork enabled Adam, even after they fired him. A fact, as Scott pointed out, made far worse by the fact that WeWork’s biggest investor—Masayoshi Son—was also a huge zealot. With that, I guess it’s not so crazy then when you think about it: one crazy asking another crazy for crazy amounts of money for crazy things.

How to avoid this 🛠️

Oof, maybe don’t siphon company money for yourself—putting investors, employees, and customers in second place? JK, I know you wouldn’t.

But more broadly, always be transparent in your decisions and dealings. Prioritize proper governance and measures of accountability. And also, if you’re a founder, consider which camp you fall in: are you a zealot or a pragmatist? Or, more importantly, consider how you can strike a balance between the two. Vision and ambition is how you sell a story and raise money, but be careful not don’t drift too far from reality. There’s a fine line between being a visionary and a liar.

When it comes to execution and being an operator, have one foot on the ground, one foot on the next step up, and your eyes wide open looking a good couple steps ahead.

Parting thoughts 🤔

While WeWork has filed for bankruptcy, it’s not all over yet. There are possibilities:

One option would be to use bankruptcy (a capitalist tool designed for companies with lease commitments) to look over its office portfolio, get out of the leases of underperforming locations, and get better deals on the good ones. AKA, strip back to the core. Kill the costly buildings, focus on a few prime locations, and gradually with a ton of caution, grow. They need to come to terms with and take ownership of the fact that they are not a startup. They need to be profitable, and they don’t deserve to trade at tech company multiples. This option still involves taking on long-term leases though and being capital heavy.

Another option would be to pivot away from master leases and long-term commitments and truly try become the asset-light operation they always wanted to be. In practice, this would be akin to “Real Estate as a Service”. Basically WeWork could run their spaces through operating contracts with the building owners, earning them fees and a share of top-line revenue. In fact, this is how the Fours Seasons and the Ritz manage their hotels.

Finally, they could become a franchising shop. Each franchisee manages costs, growth, and local dealings, and WeWork provides the guidelines and the brand power. Because they do have the brand. As Scott says:

Both WeWork and Uber have an asset that is worth billions, brands that have reached Elysium — they are the generic term for their category. WeWork’s brand has been dinged by the business failures of the past few years, but the impact of corporate missteps on consumer brands is typically muted. Airlines, for example, can’t stay out of bankruptcy court (American, Delta, and United all being recent examples), but their brands keep flying. I expect more than a few potential buyers are fielding brand equity surveys right now, gauging the strength of WeWork’s potentially most valuable asset. My bet is Barry Sternlicht brings the firm out of bankruptcy. We’ll see.

Of course none of this will work if there isn’t demand for shared office space. But, there definitely is. 75% of workers would “choose flexible working instead of a pay rise” to return to the office.

This means WeWork is in a position to do a turnaround with the right pragmatic leadership. If there’s a market for what you’re selling, there’s opportunity. Now, will they ever be worth $47B again? No. There’s far more competition in the space (excuse the pun), and nobody will ever value them the same way again, but they may be able to skirt away from pure extinction and perhaps in a couple decades return some of the billions in capital to investors—investors who hopefully have learnt their lesson.

And that’s a wrap on our WeWork post-mortem…

Thanks for reading! If you learned anything new today, you can sign up here for more issues. Also consider sharing this post, perhaps becoming a paying subscriber to support my work, or if you are a paying subscriber already, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member.

Until next time.

— Jaryd ✌️

Interested in reaching my audience of 13K+ PMs and founders?

Anytime insiders get any “out-of-pattern” payments within a few years before a filing, creditors can go after those dollars. The theory is that management and owners took cash for themselves then left the creditors holding the bag. This may help, but I’m sure there is plenty out there if you want to pursue the topic. Search on “bankruptcy claw back” or “bankruptcy preference”

https://www.romanolaw.com/disputes/preference-claims-in-bankruptcy/#:~:text=A%20preference%20claim%20is%20brought,%E2%80%9Cclaw%2Dback%E2%80%9D%20claims.

Great post. Perhaps start-ups should be looking to funds like Softbank that are hands-off, have plenty of cash, and seem to want to chase deals. In the whole saga, Softbank was the enabler and is as guilty as Neumann. I have done a lot of restructurings and messy situations like this one, and the only explanation I have for Neumann walking away with hundreds of millions is that he had something on Softbank that Softbank did not want to leak out. All of his employment agreements and other deals would have been wiped away in any other situation. But the story is not over for Neumann. Given the bankruptcy, he is at-risk for a claw back on his exit package.