The New Couch Problem

How to find the invisible obstacles in your users' lives that demotivate them from buying

Jaryd here! Welcome to ✨ the first free edition of From The Garden ✨, the column of this newsletter where I share one useful idea that can help you build and grow your product. Looking for the company deep dives? Go here.

Hey everyone,

When we think of friction, our minds immediately race to things in our onboarding flow. Things like too many questions being asked at signup, the cognitive load of our UI, our pricing being too restrictive, or maybe site speed causing a drop-off.

The list of product friction goes on. But that’s just it—we always think about our product friction. And that type of friction is usually easy to put a finger on, and also to optimize against. It’s the stuff growth teams spend a ton of time tinkering with.

For example, if we find that people are not buying what we’re putting out there (i.e. low conversion rates), the obvious reaction is we think we need to improve our product. Add some missing features. Adjust our pricing to offer a better deal, or just market ourselves better to folks.

Simply put: Most of us think the best way to win people over is to push harder.

That is all very local thinking though. Because another type of friction exists outside of our product, inside your users’ everyday lives, and in their off-platform workflows.

These are the obstacles we don’t see: The hidden frictions. Unfortunately, no funnel analysis will tell you what it is. Quantitative data doesn’t have the answer. What you have to do is go and ask folks the right questions. But, most questions we ask users won’t reveal these hidden frictions that pull them back, because often, they don’t even know what they are.

This is, to whip up a memorable name for it here, The New Couch Problem. And because we are all here to grow our products and get more customers, it’s so key that we know what it is and how to navigate it.

Just to illustrate. Imagine you’re a PM running an e-commerce site for custom-made furniture. Your customer reviews are through the roof, and you have a clear signal that people love the products they get. But you see in your data that many folks are spending hours creating their ideal furniture and adding them to their cart, but then…they vanish. And this drop-off is most glaring in the sofa category.

What do you think the problem is? What’s the friction?

The first time I heard this real case study in a Hidden Brain episode, my guess was very far off. And I bet that yours is too.

The answer?

People didn’t know what to do with their existing sofa. Most people are not sitting on the floor when they get a new couch, they’re replacing an old one. So, what do you do to get rid of the old for the new? Can you just leave it on the street? 🤷 Well, until you figure it out, you’re going to pause on hitting buy.

In this example, you’re losing many would-be customers to this hidden hindrance of not knowing how to deal with the logistics. Investing in levers like lower prices, more abandoned cart emails, or a better checkout flow may bring small gains, but they miss the real thorn in the foot. And pushing harder isn’t going to do it.

FYI, the solution was for the brand to add an ancillary service that offered to collect a customer’s old couch when they delivered their new one, and then take care of recycling. This removed the burden from the buyer and was a huge unlock in conversion rates.

This is just one of several examples of non-obvious friction outside of a product that holds people who are often already sold on a product back from otherwise pulling the trigger and making a purchase.

Here’s one important way to help find these types of issues:

We often speak to users in pursuit of discovery, get feedback about a problem they have, and then try to solve for that problem. But if we abstract out, another question that can help reveal hidden frictions is to ask why they have that problem in the first place.

Because when you find that problem, then you find the big opportunity.

Okay. Let’s talk blockers, how to find those obstacles we don’t see, and what you can do to get potential customers to complete the sale.

Quick note: I’ve dropped the paywall on this piece because it just made so much more sense to rather do a sponsored edition today. I only ever work with partners that are extremely high quality and super relevant to helping you at work. And in this letter’s case, one current partner is just so relevant to the solution to this problem, I had to recommend them. 👇

Understand your customers in the fastest, and deepest, way possible*

If you’re speaking to customers, the answers to their hidden friction often already exist. It’s in the data.

To identify themes and remove guesswork across all your customer findings, this week’s partner, Dovetail, is actually the perfect solution.

Dovetail takes in all your sources of customer info—interviews, documents, sales memos, market research, surveys, PDFs, decks, etc—and uses powerful search (with AI) to help you and your team find the answer and make customer-first, data-backed, decisions faster than ever before.

Their free plan is crazy generous. You get unlimited use of all the features, the only limitation is one project. Try it out; decide what to build next. Thank me later.

Examples of sneaky obstacles

Here are four other cases that I think highlight The New Couch Problem well. Notice how what hindered user adoption was usually:

Something subtle;

A psychological thing;

And obvious/intuitive when discovered.

(Those 3 things by the way I think are the key traits of hidden friction)

Okay, the first example is my favorite case: Instant Pot.

Instant Pot launched in 2010, and it took the world by storm. It made for great infomercials and people flocked to get their hands on one. Folks hailed it as a great at-home innovation. However, Instant Pot was really just a rebrand of a technology that had been around since the 1600s—the pressure cooker.

Instant Pot was super successful because they were a marketing-led play that leveraged a key insight into a hidden friction around pressure cookers: people were scared of them, thinking they might explode from the pressure once the lid was locked.

Yup, fear is definitely going to slow your adoption. So, their marketing brilliance was to not even mention the word “pressure” once anywhere and to build a brand and product that seemed friendly and safe.

Unlikely they’d have been so successful as The Pressure Pot 🤔.

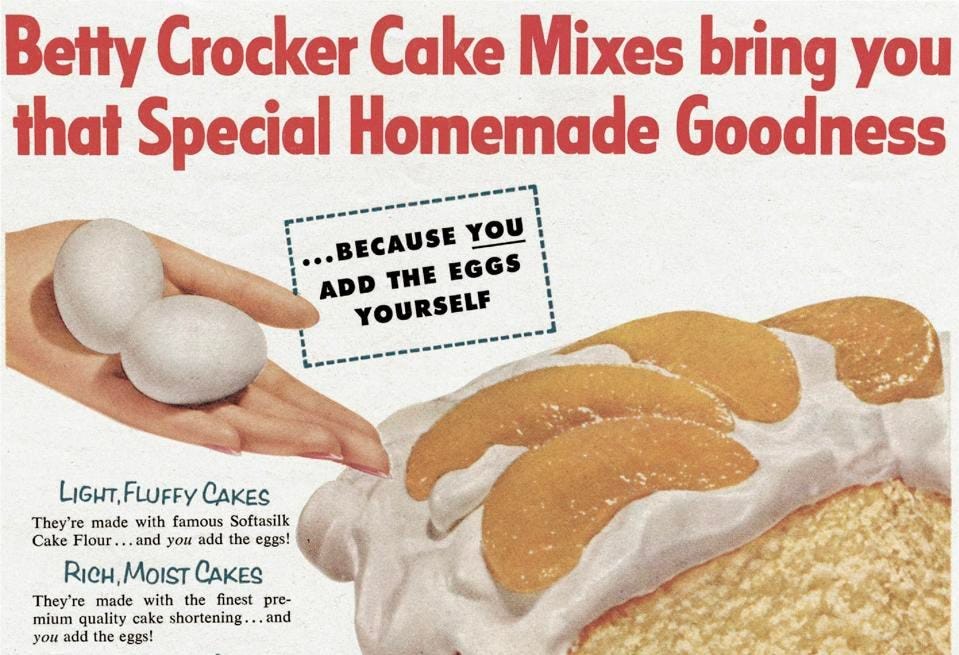

The next example is a famous one: the old marketing legend about cakes and eggs.

In the 1920s, companies like Pillsbury and General Mills created boxed cake mixes as part of a push toward convenience in the kitchen. The mix had powdered eggs and all the necessary ingredients for a delicious cake—just add water.

But, by the 50s, sales of the cake mixes had plateaued. Companies couldn’t convince more consumers to switch from homemade.

Then along came psychologist Ernest Dichter, who discovered through focus groups the hidden friction: their cake mixes were too convenient, and women (their main demo back then) felt guilty using them.

A huge insight that led to the smallest of changes—they simply tweaked the recipe to require one or two fresh eggs to be added, thus forcing a bit more planning and work that gave consumers more ownership.

Sales skyrocketed.

Okay, an example outside of the kitchen…

Stacy Alonso, working at a shelter for women and children experiencing domestic abuse and homelessness, noticed a recurring pattern: Women would often appear at the shelter, stare at it for hours, walk up to the door, and then walk away.

Puzzled, she investigated and discovered a hidden friction: the "no pets allowed" sign on the door.

Alonso was also shocked to learn that in many cases, without family to stay with or money for a hotel, women go back to their abusive situation to remain with their beloved pet.

Despite the clear benefits of escaping abuse, many women couldn't bear to leave their pets behind. The solution? They created a facility on the same grounds where women could safely shelter their pets, removing this significant barrier to seeking help.

“They check in to the women’s shelter, and the pets are right next door at Noah’s,” she told CNN. “And they’re free of abuse and safe.”

What an awesome illustration of this problem.

The final example I thought I’d share isn’t specific to a brand, but it's a good general one for tech products. It applies because it checks the three boxes of a hidden friction: Subtle, Psychological, and Intuitive.

Credit to Max Dixon for this concept which I learned in Lenny's Podcast ep: The Surprising Truth About What Closes Deals

It's what Matt calls FOFU: The Fear of Fucking Up.

In short, in the B2B software buying process, people often don’t need to be convinced that some new product is better than the status quo. They already know the solution is great and will benefit them, so no amount of FOMO will get them to pull the trigger.

The problem is they’re afraid because their reputation is on the line. The fear of making mistakes, looking incompetent, or disrupting existing workflows is a really powerful deterrent. People often fall back to the safe bet—what they do today.

To sell really well and overcome this hurdle, as Max says, “We've got to help instill the confidence in the customer that you're making a great decision. I've got your back. You're going to look like a hero, not like a fool.” In other words, you need to know when it’s time to stop pushing benefits and to start focusing on minimizing any risk concerns they have.

Two main ways to find your product’s invisible and demotivating force

The pre-launch approach

If you want to find any hidden friction before you launch your product, then during discovery, you need to be like a chef peeling away the onion. You do this by asking lots of probing "why" questions to understand the root cause of the problem you’re solving.

For instance, open-ended questions like "Why do you think this issue arises?" or "What do you believe is the underlying reason for this challenge?" can be very revealing.

The name of the game is encouraging users to share their thought processes, motivations, and contextual factors that contribute to the problem.

You want to know things like whose opinion they care about around their usage of your product, and what they do before and after they have the problem.

The more you understand the big picture in your user’s life, the better you can create an incredibly helpful solution to one small aspect of it.

The Fix-it! approach

If you’ve already launched a product, then it should be pretty easy to pull up a log of prospective customers who’ve abandoned purchasing whatever you’re selling.

From here, you want to do a deep dive into the needs and backgrounds of disappearing customers.

We did this at my first startup, which was a talent<>job marketplace for models, actors, and creators. We saw that producers were posting projects seeking models, models would apply that fitted their criteria, and they’d view the applications, but they would not request to cast them.

We were confused. All the signals of a booking were there.

So I went to their offices and spoke with them. What I learned was that they were hesitant to book because many of the models who were applying had agents, and the producers who knew the agents didn’t want to upset their friends in any way.

So, despite a far more convenient and budget-friendly way to book talent (something they needed), this hidden friction of not wanting to “step on anyone’s toes” was blocking transactions.

We fixed it by working more closely with the agencies, establishing partnerships, creating new types of filters, and addressing this concern directly in our messaging and job listing experience. This was a huge unlock for us.

Some other quick ideas

Use session recording tools like Amplitude, Sprig, or Hotjar to watch actual user behavior and identify points of hesitation or confusion.

Implement event tracking to measure the time between key actions. Unusually long gaps may signal hidden friction. From here, you can go speak to these people to understand what may be happening behind the scenes.

Read the reviews of competitors and look out for subtle, not directly related to the product, questions/concerns people have.

For each feature you have, consider how you want people to feel when using it. And from there, use language and design that aligns with users' emotional state and goals.

I’ll leave you with this: Just like there was for us at my startup—there could easily be a hidden friction out there holding your product back from growing at a much faster clip.

The main point of this essay was less about a clear action and more about getting you thinking about it as a concept, and putting it on your radar. It’s not always about the frictions we mostly try to optimize for.

It’s often something more human that pulls people away from an action they’d otherwise be ready to take.

Thanks for reading. I’ll see you next time.

—Jaryd

Hi Jaryd, great post, thank you. An excellent book -- Pattern Breakers: Why Some Start-Ups Change the Future -- just came out from Mike Maples Jr., the VC from Floodgate. I think I learned about him from your blog. You may find a lot of pearls to share with your readers.

...such a useful issue man...so many insights hard to pick just one but unlocking your customer’s hidden friction is huge...knowing what you don’t know can be such a great push into new spaces...and anytime you get a greater majority of the problems on the table the better odds for success...great work man...