ByteDance | TikTok: Origins, How They Grow, and The Future of The Internet

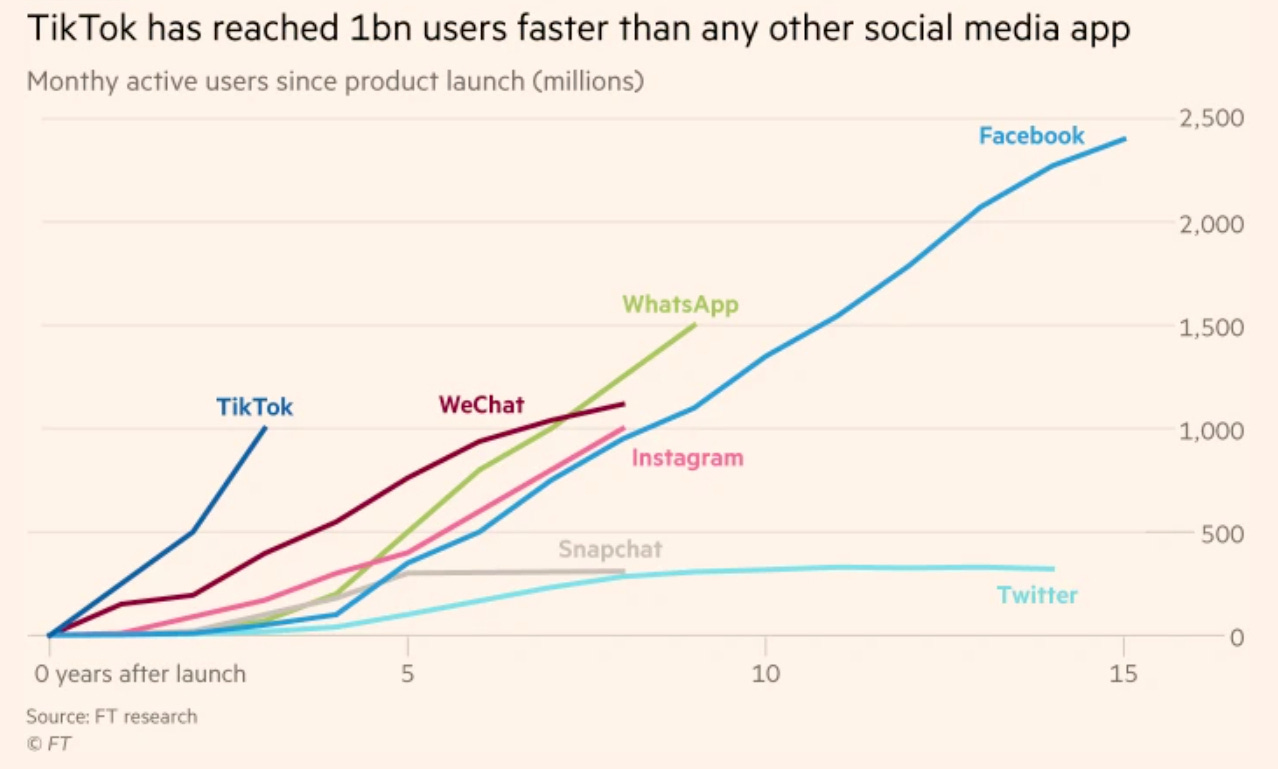

Understanding the growth forces behind the most valuable startup on the planet, and breaking down concrete lessons from TikTok's road to 1B MAUs.

👋 Welcome to How They Grow, my newsletter’s main series. Bringing you in-depth analyses on the growth of popular companies, including their early strategies, current tactics, and actionable business-building lessons we can learn from them.

Hi, friends 👋

Today, we’ll be tackling what may be our most ambitious deep dive thus far. Simply, due to the sheer depth of ByteDance, the parent company behind TikTok, and of course, the risks in writing this.

I spent a fair bit of time wondering if this was territory I wanted to take us into. As you likely know, the future of TikTok is unknown in the US, and there are definitely split feelings about that. Including, I’m sure, from you guys reading this right now.

With opinions ranging from the suppression of the people’s voice and loss of livelihoods to Chinese spying and influence. I’ll give this important topic more coverage at the end for more on what this means for the broader Internet, and why we should all care. In short, I think banning TikTok is a really bad idea, both geopolitically, and in terms of what it would mean for free speech and Internet privacy as we know it.

But this isn’t what you’re here for. You’re here for practical lessons and real-life examples on building and growing products from the most successful companies out there.

Well, ByteDance/TikTok are unequivocally that.

So, that’s what we’re doing today first and foremost. An investigation into a truly fascinating company that most of us know far too little about.

Whether TikTok sticks around or not in the US due to political/regulatory/legal issues — they are without a doubt a phenomenon still worth studying. There are just so many interesting mechanics going on that have made TikTok the sensation, and growth machine, that it is.

So, wherever your feelings about TikTok lie, I hope you’ll stick with me as we unpack not just the mobile slot machine that is TikTok, but also ByteDance — the most valuable private tech company on the planet.

Onwards we go. 🕵️♂️

[NB: If you’re reading this in your email, click here to read the full thing]

Here’s what you can expect today:

[Act I] Aggregation, AI as a Service, and the first byte of the content pie

[Act II] Short-form video, an attention factory, and e-commerce

[Act III] Musical.ly, hello TikTok, and paving their own Silk Road

How TikTok Grows: The road to 1B MAUs, and what we can learn from it.

Paid acquisition to kickstart a network

Using the product as the main growth driver

Going deep on creators, and the UGC [content X data] flywheel

Collecting Infinity Stones: TikTok’s 7 Power

The Endgame: The “RESTRICT Act”, banning TikTok for Americans, and the future of the Internet

Favor: if you enjoy this post, I’d really appreciate a quick click of the little heart button—it helps more people discover my writing —or share it with a curious friend or two. 🙏

Let’s get to it.

ByteDance: The AI startup you probably know very little about

The Chinese company behind TikTok, currently valued at a whopping $225B, is the most valuable startup in the world. With backing from the likes of Sequoia and Softbank, and employing over 150,000 people across 120 cities, their valuation is greater than the US’s top 3 private unicorns (SpaceX, Stripe, Canva) combined.

Most of the time, because of their ecosystem of news and entertainment aggregation products—and being dubbed China’s Content King— they’re considered a (social) media company.

This assumption, however, is wrong.

Founded in 2012 by Zhang Yiming in a small Beijing apartment, they are, in fact, an AI company. That’s not a secret they’re hiding by any means. But they’re doing a pretty good job at operating outside of the current limelight of it all since none of us are including them in the AI conversation. We’re too busy turning a photo of the inside of our fridge into a recipe and getting inundated with more something-something AI tools.

So, we’ll start with a little backstory here.

11 years ago, while we were waiting to see if the Mayans were right, Zhang was deeply curious about the opportunities in the then-nascent mobile Internet market in China — specifically, in search. He saw two problems. First, Chinese smartphone users were struggling to find relevant information in the apps available (Google Search was banned). Second, the search giant, Baidu, was squeezing in undisclosed advertising in their search results.

So, as founders do, Zhang set his eyes on changing things. His approach? Push relevant content to people by generating high-quality recommendations through artificial intelligence.

To get things in motion, Zhang got to work on building ByteDance’s first product, Toutiao (meaning, Today’s Headlines).

Act I was underway.

[Act I] Aggregation, AI as a Service, and the first byte of the content pie

Toutiao, to package it simply, is a news aggregator app that scrapes content from the Internet and pushes it to people's feeds based on their interests.

When Zhang pitched it to investors in 2012, he made it clear that Toutiao’s value was really the algorithm behind it, powered by AI and machine learning, and how they used big data to analyze a user’s news preferences and offer them very curated, adaptive, content. Unlike other platforms, Toutiao didn’t need any explicit user inputs, social graphs, or product purchase history to rely on.

And still, despite being consistently tagged and evaluated as a news company during fundraising, Zhang was insistent they were an AI company in the search and social media business.

Investors were skeptical, not seeing the difference between them and the other major online news portals. Talk about missing the forest for the trees.

AI(and monetization) as a Service

Today, Toutiao is one of ByteDance’s flagship products. Each user is measured across millions of dimensions, and its extensive personalization has made it one of the most popular content discovery platforms in China. But, far more significantly, the development of their AI models for this first app became the bedrock of ByteDance — as they essentially created a proprietary AI as a Service for themselves, which they started deploying across each new app they built. This AI became ByteDance’s middle platform.

And if you’ve ever used TikTok, you know it’s good. Very, very good.

When Toutiao launched, they didn’t have any of their own content — it was all third-party stuff being pulled together. But, as their generative model got better, they soon started using their own AI to create unique content to serve in their algorithms.

Going a step further than merely serving up content, Toutiao’s algorithms also create content: During the 2016 Olympics, a Toutiao bot wrote original news coverage, publishing stories on major events more quickly than traditional media outlets. The bot-written articles enjoyed read rates (# of reads and # of impressions) in line with those produced at a slower speed and higher cost by human writers on average.

Okay, so we know the underlying AI behind Toutiao is their secret sauce, and we know it’s reusable. But it doesn’t just distribute content and drive engagement, it’s also ByteDance’s profit center as the AI simultaneously uses those same 1M+ data points to personalize ad recommendations and automatically distribute them strategically at the right time and place. This aligns monetization very closely with the product. As Anu Hariharan (YC) explains:

Of the many things that Toutiao does, one element that is core to its model more than any other: it is good at identifying what its users want to see. It is fitting, then, that its business model maps perfectly to that strength. Toutiao generates revenue by matching relevant ads to users, using the same proprietary technology behind their content targeting. This has three important benefits:

First, it reduced the impact of monetization on the user experience – and may have actually improved the experience! Users typically consider ads as intrusive and degrading to their experience, but ads aligned with user preferences are less so. In serving ads that are highly relevant to a user’s interests, Toutiao in many ways acts as a product discovery mechanism.

The second is that it increased the rates that Toutiao could charge advertisers. One of the key problems in advertising is identifying how to selectively place your ads in front of the highest potential customers, and advertisers spend countless hours and enormous sums of money trying to target effectively. Toutiao’s technology, which solves this targeting problem natively, represented a solution and saves advertisers from paying a big premium for it.

Third, since the primary use case is to read and view content, users are more receptive to seeing relevant targeted ads and therefore there is more inventory available to advertisers.

And it’s effective. 💸

Between 2012 and 2015, the success of Toutiao was what set ByteDance in motion, laying the foundation for the steeper growth curve that followed. And the app's rapid success can be attributed to a few important things. Folks, take note.🛠️

The forces behind Toutiao’s incredible growth

Timing, and seizing the opportunity. Smartphone penetration was still low in China in 2012, especially compared to the US (12% vs 35%). The other content providers hadn’t yet developed mobile apps or mobile-friendly sites, so true mobile-first information and entertainment were rare. Zhang knew there was an opportunity here before the explosion of smartphones (shooting up to 65% by 2014) and subsequent mobile Internet adoption, and he was right. Which made what he did below so smart. 👇

Channel partners for distribution. Zhang worked with phone manufacturers to get the app pre-installed. Meaning, when someone got a new phone—much like U2’s album—it was there if you wanted it or not. And brilliantly, he made sure it was dead simple to try. 👇

Zero friction. Toutiao was super easy to start using. Once it was downloaded, you were set. No accounts/passwords, no need to link any social profiles, and no questions about your interests — all steps other apps were losing people through. Rather, the app created a shadow profile based on your device ID. The design was also very intuitive with no learning curve. You just scrolled, and the more you did, the more relevant the content got.

A novel hook. Toutiao bought users a unique value proposition. It was the first time they could just go to one place, instead of having to hop around to fulfill their information diet. By owning, centralizing, and optimizing the distribution of content, they reduced the time a user needed to find a relevant article to nearly zero. And they focused on a good beachhead. 👇

A niche GTM focus. In a book move from a go-to-market perspective, they honed in on one initial category to wedge themself into the picture — “soft news”; AKA celebs, gossip, lifestyle, and pop culture. This stuff was more scattered across the web, with ranging quality, compared to more reputable “hard news”, making a high-quality recommendation model in this category particularly valuable. Of course, they pushed beyond this once they had people's attention. 👇

Expanding into a content destination. Toutiao started to evolve from a pure aggregator to a first-party destination for various types of content. They launched a strong incentive program through revenue sharing to attract more content creators to the platform. This made them a deeper platform for content generation, consumption, and connections.

Immediate monetization (aligned to the product). From the get-go, Zhang prioritized proving a solid business model behind Toutiao. This led to early cash flow, which they heavily invested back into AI development, improving the feed's personalization, leading to a better underlying middle layer (and user-facing product)…repeat.👇

Continuous product improvements. Zhang made sure the team updated the app almost weekly throughout its first year. This consistent innovation, iteration, and improvement of their features and algorithms drove retention over time and made sure they moved quickly to embrace feedback and larger trends. 👇

Adapting to meet market demand. Unlike Vine (who we saw missed this mark), Zhang had his ear to the ground. He noticed there was a big uptick in video content by 2014, as well as better tech that improved the delivery and consumption of it. And instead of being stubborn about their core format (listicles, long-form content, and news), they were quick to expand to other formats when the data suggested they should.

They also applied many of these lessons to their playbook for TikTok. 🤔 Now, segues are hard to find, but this is a nice one into Act II of ByteDance’s evolution, which came with their second product, Douyin.

[Act II] Short-form video, an attention factory, and e-commerce

Like Toutiao, you’ve also likely never heard of Douyin.

Luckily, it’s super easy to explain. It’s a nearly identical clone of TikTok for the Chinese market (with a few more features). Same logo and all. Except, it was TikTok before TikTok was.

While Toutiao had become unencumbered by formats and was also pulling in video content, it wasn’t really becoming a platform where a new category of emerging media—short-form video (SFV)—was finding a place. For starters, the handful of other apps that were in this SFV space had content that was locked in their apps, making scraping hard. Second, there was a positioning problem, as SFV was more snackable entertainment value than news.

But, ear always to the ground and hyperaware of the changing landscape, Zhang had been seeing a gradual increase in the popularity of SFV since 2011. And because his initial vision for ByteDance was global, he had a pulse on his market across the world.

So, when Vine came along, Zhang was acutely aware. Their 2013 launch, and rapid ascent in the US, was a milestone event for this type of content. In short pace (as we saw in Why Vine Died) they set in motion an explosion in homegrown, experimental, and bite-size content. And they essentially defined the template for successful (despite failing themselves) short-form, mobile-first, video.

Zhang, not wanting to lose out on people’s attention, and also seeing a key advantage in their AI model, began building ByteDance’s SFV contender — taking inspiration from what had made Vine successful, as well as another new app, Musical.ly (more on this soon).

200 days later, in September 2016, Douyin—the short-form music video app for young creatives—went live. Coincidentally, just one month before Twitter announced the shutdown of Vine.

It came with a huge library of assets (like filters and music) for users to easily create and share up to 40s music videos. And people in China went nuts for it. In their first year, Douyin had 100M users, with over one billion video views every day. Today, half of China’s population opens the app…every day.

Here’s why it was such a success:

Built on top of existing AI. As Zhang said, ByteDance’s real product is the underlying AI. So, they deployed the advantages they’d built in content and ad distribution from Toutiao into this second consumer product. Meaning, off the bat, they were nailing personalization and monetization.

Cross-promotion to Toutiao’s massive audience. Douyin leveraged the existing user base ByteDance has established through cross-promotions, courting loads of existing users (and all their preferences) over to try Douyin.

Rapid improvements for the SFV experience. By exploring users’ habits, they continuously updated and optimized the product infrastructure. For example, they tested and launched the now ubiquitous swiping up and down to switch between videos — creating a super sticky UX, as well as a more rapid way to gather user data.

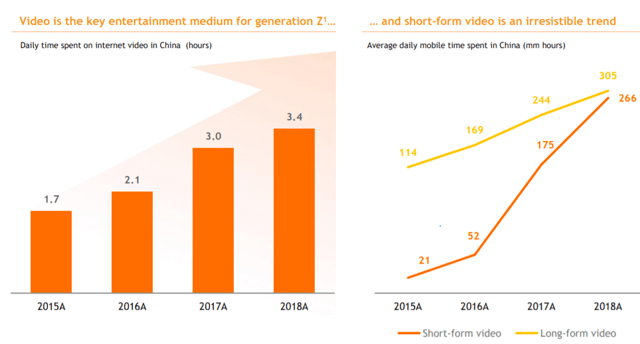

Impeccable timing. Similar to how Zhang nailed the timing of Toutiao, Douyin came to market just before an explosion in short-form video adoption in China. Just take a look at these charts. 👇

1) The SFV trend line in China (note 2017 uptick)

Looking specifically at the chart on the right — you can see as Douyin entered their first year (2017), the time people spent watching SFV shot up 237%. That’s a nice wave to catch. 🏄♂️

As people spent more time each day glued to their screens, the total addressable market for attention was growing.

And where there’s attention, there’s commerce.

2) Global SFV monetization potential

While we’re talking about money here…🫰

We covered how ByteDance’s underlying AI product makes for a great advertising business. But with Douyin, a second business model emerged, helping diversify their revenue.

E-commerce.

Throughout 2017, Douyin allowed creators to promote third-party stores in their videos and live streams. This introduced a basic affiliate model into the platform — another way for creators, and ByteDance, to monetize. But Douyin was quickly claiming more and more of people's online time, making Douyin an important destination for brands.

So, realizing their value—and how much value was moving through their platform—in 2018 ByteDance launched their own comprehensive selling tool to capture more of it. Simply, creators could make Douyin Stores of products, and as people consumed (now shoppable) content, they would get automatic pop-ups and embedded links to directly purchase products inside the app. Of course, leveraging their existing recommendation algorithms to serve users relevant shopping content.

And each time a user bought something, Douyin’s algorithms got more data, and they got a solid 5% of the sale — creating a lovely new profit center.

As an aside: From 2020 to 2021, Douyin expanded in-app e-commerce from merchandise to local services, like restaurants, flights, hotel bookings, meal delivery, movie tickets, bike rentals, and more. So, pretty much whatever users could discover from creators, if there was a transaction to be made, ByteDance was there to facilitate it. 🏦

Okay, let’s recap what we’ve seen so far.

Douyin’s success proved that ByteDance’s AI-powered middle platform could (1) be replicated in various content categories, (2) be deployed across separate services, and (3) generate different types of revenue.

Not too shabby! 👏

The next question Zhang started thinking about, was whether this core product could work outside of China.

As he said, “China is home to only one-fifth of Internet users globally. If we don’t expand on a global scale, we are bound to lose to peers eyeing the four-fifths. So, going global is a must.”

And go global they did. 🌏

[Act III] Musical.ly, hello TikTok, and paving their own Silk Road

To understand ByteDance’s astonishing success with TikTok (the internationalized version of Douyin), we first need to go back a couple of years, across the Pacific Ocean to Mountain View, San Fransisco.

Specifically, to Alex Zhu sitting on the Caltrain in 2014.

While watching a group of young teens commuting, he observed some interesting behavior that sparked a game-changing trajectory for a venture-backed app he was working on, Cicada.

Cicada was an educational social network app, specifically focused on SFV. Massive online open courses (like what we see on Udemy) were popular, but knowing the low completion rates of courses (~10%), Zhu’s idea was to make educational content more bite-sized and consumable on the go. Unfortunately, as Zhu recalls, “The day we released this application to the market we realized it was never going to take off. It was doomed to be a failure.” And in Alex’s reflections on why — we can see how these lessons weaved into his next idea. 🤔

First, if you want to do a content-based community, the content and creation has to be extremely light -- something that you can finish within a few seconds, not minutes.

The second lesson was that in the early stage of building a community, it’s not realistic that people will interact a lot with their existing friends: it’s about getting attention and making new friends and followers who were unknown before. Because the users are strangers to each other, the content has to be extremely entertaining so you want to follow new people and form that relationship.

The last lesson we learned is that it’s always young people who are early adopters in new communities and new tech in general. They are curious and looking for new apps and social media, and also very willing to spread ideas word of mouth, so you don’t have to spend a lot on marketing -- they will come to you if you can make your app compelling to this group of users.

And, while watching those teens, he had an idea about how to change things for Cicada. 💡

Observing their behavior, 50 percent were listening to music and the other 50 percent were taking photos and videos with their speaker on top to add music. Teens are so passionate about social media, photos, videos, and music, that it made me think, “Can we combine these three very powerful elements into one app and build a social network for music videos?”

— Alex Zhu

So, Zhu pivoted to a make-your-own-music-video app; baking in music, videos, and a social network element to attract the early-teen demographic.

30 days later, in July 2014, they launched Musical.ly. Immediately, they saw the numbers were much better than before. Around 500 people were downloading it a day, but more importantly, they kept coming back.

For the next 10 months, Musical.ly grew, but not at the pace necessary to get them to default alive. Then, two small things changed that:

They repositioned from a music-videos app to lip-syncing one.

They made a tiny design change, sparking viral growth.

👇

1) Lip-syncing: a lesson on positioning

Then something really strange happened: every Thursday evening, there was a spike in app store downloads. We were so puzzled, and did a lot of research trying to answer why. We finally found out that Spike TV was airing their show Lip Sync Battle on Thursday evenings, and after the show, people used “lip sync” as a keyword to search on the app store, and found us. We decided we should highlight lip sync as a primary use case for the app to make it even more compelling for our teens, and made some major design changes.

We didn’t add any new features, just made lip sync more prominent in the app. Since that update, we saw a radical turning point in our downloads, and quickly we rose to number one on the app store across categories.

— Alex Zhu

By being inquisitive about fluctuations in their data and digging into what people were organically doing on the app, Zhu and his team discovered a game-changing insight; and they leaned in hard.

Creating a music video is obviously a lot more work than just lip-singing over a popular track. And this goes back Zhu’s first lesson from Cicada’s failure, “if you want to do a content-based community, the content and creation has to be extremely light -- something that you can finish within a few seconds, not minutes.”

Takeaway: sometimes the hook isn’t a product change, it’s a positioning thing.

2) Repositioning the logo: a lesson on sweating the small things

We’re proud, social, creatures. So, naturally, after creating a video of ourselves lip-singing a Taylor Swift song with our grandma, we’re going to share it.

And Zhu and his team saw this was happening, but traffic from other social sites where people were sharing their videos, was marginal.

After some analysis, they saw that their watermark logo on the videos was getting cropped on Instagram and Twitter. So, they came up with the most basic of ideas. Let’s test moving the Musical.ly logo.

When they did, growth exploded.

Two months later, they hit the No. 1 app on the Apple charts. And a year after that, they had 70M downloads, with 20M users active each month.

But as you may know, there’s no such thing as Musical.ly today.

TikTok X Musical.ly, and ByteDance’s road from China to the world

At the same time, back in China, Douyin was becoming a powerhouse; and as I said, Zhang had his eyes on becoming a borderless company.

So, in 2017, they internationalized the app, called it TikTok, and in an unconventional move for a company expanding geographically — simultaneously launched it in more than 150 countries.

Except, not America yet.

But not only was Zhang keeping an eye on Musical.ly, but he also took a lot of inspiration from them in building Douyin. Eagerly wanting to get big in the US, he saw a great opportunity to piggyback on the audience they’d built, helping break TikTok into the lives of US teenagers.

So in November 2017, ByteDance acquired them for $1B and got to work on integrating TikTok and Musical.ly — with a specific strategic focus on bringing ByteDance’s superior AI together with Musical.ly’s users and existing interest-graph.

Then, in August 2018, Musical.ly stopped its service, and all 100M users and their data were merged into TikTok.

Touchdown. ByteDance was making in-roads in the US. 🏈

Instantly, Zhang made a huge paid-growth push to gain early traction — dropping a hefty $3M per day on Facebook/Instagram ads. 😐 2 months later, TikTok was the most downloaded app in the US.

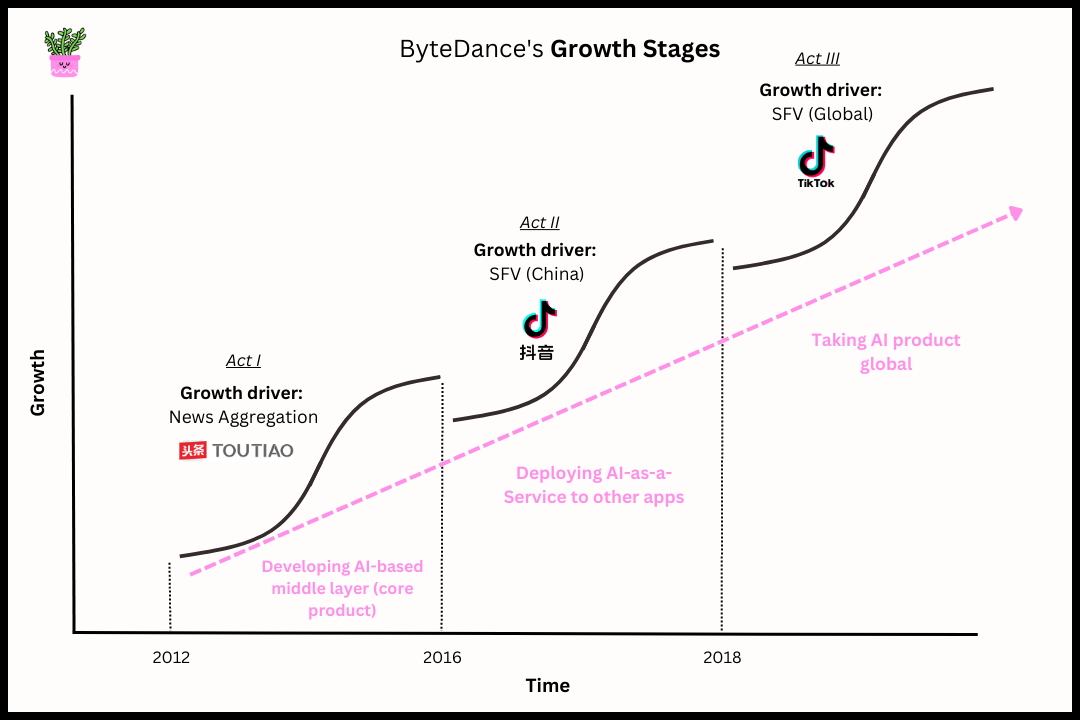

Okay, so far we’ve covered ByteDance from 2012 to 2018, from Act I through to the start of Act III. We can now summarize their growth stages like this: 👇

Each growth inflection there is clearly driven by the launch of a new product, where each one was built on top of this shared middle layer, and existing network of users and data. What’s more, for each new product using ByteDance’s series of shared services (like their recommendation engine), the shared services improved for all the others products too.

This fits Elad Gil’s “Product to Distribution” philosophy: Build the best product on the market, grow the user base aggressively to create a direct relationship with the network of users, and then use that network to launch new products. Facebook is a classic example of this with both Instagram and Messenger. As is Google with Search, YouTube, Gmail, etc, and even compounding it with Android.

This creates a stunning competitive advantage. As Aakash Gupta says:

Via the middle platform, ByteDance has taken a page out of the AWS playbook. Instead of developing technology that is only useful for one product, each service is built for the corporate parent. The company multiplies small advantages across every layer of the tech stack to create a durable advantage. These days, operating in the ByteDance ecosystem is like operating in its own technology world.

The lesson for product people is to decouple ML services. It’s tempting, for speed, to build separate technology for every product. But abstracting services helps the company build an enterprise edge in that technology, instead of just in one product.

So, let’s go deeper into the current stage of ByteDance, Act III, specifically around their most successful product, TikTok.

Ready to unpack the growth mechanisms of one of the most successful apps of all time?

I hope so, otherwise, the rest of this piece is just me shouting into the void. 🫠 Also, this next part is where things can super interesting and tactical.

Let’s do it. 💪

How TikTok Grows: The road to 1B MAUs, and what we can learn from it.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Paid acquisition to kickstart a network

Using the product as the main growth driver

Going deep on creators, and the UGC flywheel

Collecting Infinity Stones: TikTok’s 7 Power

Let’s start with the elephant in the room…that $3M/day ad spend. 😵💫

Paid acquisition to kickstart a network

Clearly, ByteDance flooded the world with marketing — with a heavy push on user acquisition and PR in 2018 and 2019.

The goal?

Build a network for TikTok as fast as possible and win in each market, simply, by crushing other SFV competitors by outspending them.

It’s important to note, rushing too quickly to growth via paid can be problematic if you don’t have your fundamentals right, like a product people want and things like channel/product/model/market fit. But Douyin had proved these things already, and in a rapid push to become the number #1 SFV app globally, Zhang tapped into the cash cows of Toutiao and Douyin to make that happen.

As Elad Gil says, sometimes it’s worth spending money upfront to kickstart a valuable network:

Although there are many companies that grew without spending a dime acquiring customers (Google, FB, Twitter), when I think back to the original Internet bubble, there were lots of companies that seemed to thrive due to their raising tens of millions of dollars to build a brand and acquire users in what was a very noisy environment. Indeed, there are a number of companies that were able to scale because they spent tens of millions of dollars buying users. Examples include:

PayPal (who paid $10 per user to join the PayPal network)

Monster.com (remember the Superbowl ads?)

Amazon.com (went public in 1997 and wasn't profitable until 2001, with costs here, were spent on, amongst other things e.g. logistics and market share)

I think there is a fundamental class of business that could be very successful in emulating the bubble days approach to building a userbase. In particular, there are a number of entrenched businesses with strong network effects (e.g. eBay) or brands (e.g. Amazon) or logistical advantages (Amazon). The lean startup approach may never overturn these apple carts. The way to challenge these incumbents is to spend a lot of money to build brands or acquire users in order to overcome these effects.

— via Fat Startup: Raise $100 Million For Your Next Internet Company

At first, TikTok’s 30-day retention of new users in the US was as low, sitting at 10%. Most likely, due to targeting a broad audience with content still very similar to Musical.ly and Vine. But as more users came in, more creators joined, leading to more UGC and kickstarting a powerful content and data flywheel (more soon).

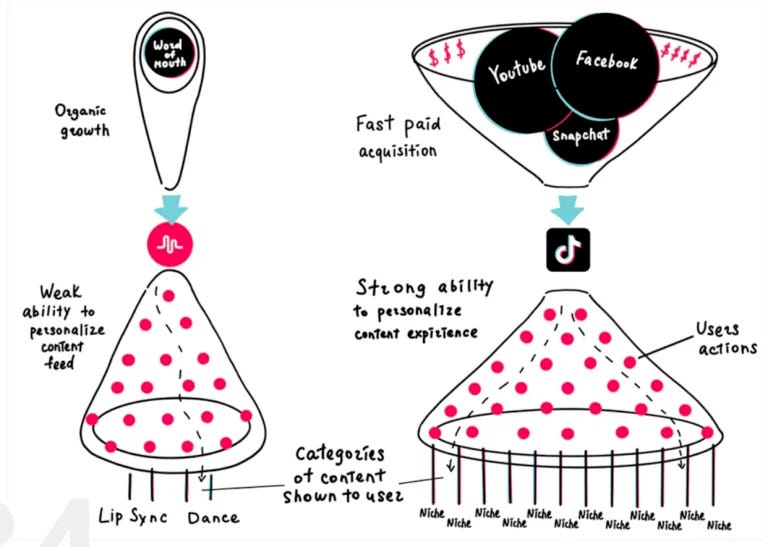

This visual illustrates what ByteDance did with the newly merged Musical.ly [left] and TikTok [right] in 2018, leading to a huge surge in growth post-merger: more users via paid → more content → superior classification and recommendation algorithms → more discovery of niche, hyper-personalized, content → higher retention rates → more word-of-mouth growth

And combining the network value with a product hyper-optimized for easy adoption, retention, and sharing — TikTok’s growth was off to the races.

Today, their monthly retention is ~65% (vs Instagram's 56%, and TikTok is used by 30% of everyone who uses the Internet.

Product as the growth driver

Besides the phenomenal middle-layer algorithm under the hood — if you’ve ever spent any time on TikTok, it’s hard to argue that one of the main factors driving their phenomenal growth isn’t the product.

For starters, look how simple it is to try.

Immersive onboarding

For any app, B2C or B2B, onboarding is crucial to nail.

And TikTok is an excellent example of a consumer product using immersive onboarding. In other words, where you get set up and learn about the product by just using it.

In terms of steps, they first offer pretty much all the single-sign-on options during account creation (like Google, FB, Apple, and Instagram) — removing basically all friction in the account creation phase. FYI, when they launched in 2018, you didn’t even need an account. They created a shadow profile based on your device ID.

In the second step, they optionally ask about your interests. If you tell TikTok you want DIY videos, comedy, news, animals, or stuff about boats here, you’re giving them some explicit data to work off as they prepare your personalized home feed (just seconds away). But, they don’t need it. As soon as you start using the app, your implicit data quickly helps their recommendation engine learn about what you want to see.

And that’s it, the only “onboarding tutorial” they give you is when you land on the feed and they tell you about the single primary action you need to know about…swipe up for more videos. You can use TikTok with nothing but that one motion. So, if you’re new and you spend too much time on a video, they will remind you again to swipe.

To test this all out, I created a new account, skipped the interest question, and once the app was downloaded, in 10s I was watching my first video. Importantly, it was already playing.

No need to start it, and no confusion about where to go.

TikTok made sure they were providing me with immediate value. Showing, that in the span of a few breaths, they’re helping users see the promised land.

This, unlike other social media platforms, can happen immediately because they don’t ask you to follow anyone or connect with friends. 👇

No reliance on a social graph

Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter all rely on a social graph. If you don’t have any FB friends or follow any pages, your feed is going to dry. That’s where that iconic FB insight of “7 friends in 10 days” came from — they needed users to build a basic graph so they stick around.

But, a huge part of TikTok’s beauty (which we’ll get more into) is how the feed is driven by meritocracy and discovery, and not followers and search. Going back to my onboarding journey, instead of figuring out who I should follow and add to my “network”, I was just served a bunch of content. Which soon, becomes hyper-personalized to me based on thousands of objects and tags analyzed in each individual video, along with my view history, re-watches, watch time, likes, comments, shares, etc.

And even when I used TikTok daily a while back, I didn’t follow a single person. Unlike Instagram, where it’s about seeing your friends and family (at least for me), TikTok is the largest social media company that has little/no reliance on a social graph.

What’s more, TikTok’s “anti-social” approach may have more staying power than traditional social media models that suffer from context collapse, where the value of the product eventually goes down as a user adds too many friends.

This leads to an important point: TikTok is about discovery over searchability. Sure, you can go and actively look for things on the app (and people, especially Gen Z, are in fact using TikTok as a search engine now more than Google), but the intent in this type of search is different. Searching in TikTok is more about digging deeper, than trying to find stuff to watch.

In this sense, TikTok is like a TV without a remote control.

Many products follow the “remote control” model by not taking an opinionated view of what users experience. I recently signed up for Twitter and Reddit and while there’s a wealth of interesting content on both platforms, it’s on me to dial into the right channels. Even on Netflix, there is often a sense of overwhelming choice. Rather than endless rows of recommendations, I wish they had a “surprise me” feature in which they auto-play the best pick for me in that moment.

Selection is a selling feature for new users, but it can quickly become an unintended bug for retained users that face a constantly growing surplus of options.

TikTok has fully embraced the Internet assumption of abundant selection, along with the consumer desire to see only the best. None of this would be possible, however, without a powerful algorithm that quickly and confidently learns your preferences to determine what is best, for you.

— Linda Zhang, via Product Lessons

And without the need to make any decisions, you have infinite content to discover in search of your next dopamine hit. 👇

Bite-sized content → atomic consumption

Short-form videos are by far the most engaging type of content, and pretty much all of the SFVs on TikTok have some important things in common (which science shows, are the 5 key elements that make an idea stick)

Simple (short, basic)

Unexpected (curiosity gap)

Concrete (i.e learn about Ukraine, DIY, and recipes)

Emotional (funny, music-driven)

Story (e.g comedy bits, recommendations of things to try)

This endless feed of SFV leads to an insane amount of video content (comparatively) being watched each time a user logs into the app. As an aside: this is why I took a break from using TikTok a couple of months ago.

SFV also means less commitment each time a user opens the app. Unlike going to Substack to catch up on some newsletters (which as you know by reading mine, takes time) — TikTok unlocks rapid dopamine hits. Making it “an ideal app” to open up when you have even a minute of idle time.

And on the note of dopamine...TikTok’s feed (which, to be clear, I definitely think is for the worse) works just like a slot machine. Each swipe of the thumb releases a new variable reward. 🎰

A variable reward—for the non-psych folks like myself—is a gratification token used in the Hook Model, delivered intermittently, meant to keep users repeating the same action in the hope of another reward. It’s a reward system powerful for driving attention, focus, and repeated action.

In other words, it creates habit-forming behavior. And this combination of a very low cognitive task (a swipe), with a high variability reward, makes TikTok a textbook example of addiction-forming design

And importantly, this atomic consumption driven by each pull of “the slot machine” trains each user's algorithm very fast. In the time it takes to watch one 10-minute YouTube video, TikTok can capture data from 40, 15-second videos — where each video unit is designed for speed and clarity of signal-gathering.

More ways to discover content in different niches

With an endless supply of bite-sized videos, TikTok has created unique discovery vectors.

This means you can either just scroll through your feed forever, or skip into an alternative thread with related videos sharing the same hashtags, video effects, music, or creator.

How far and wide you go are then all added to your data profile, helping the algorithm curate your feed even further to your known (and unknown) interests. Sometimes, to a creepily accurate degree.

And, the more relevant content you find and enjoy, the more likely you are to share it. 👇

Social capital and “Ingredient Branding”

Sustainable word-of-mouth growth is probably the gold standard when it comes to a growth engine for your business.

The thing is, creating word-of-mouth growth is hard and can’t be forced. It’s something that just happens. But, what products can do though when they see this behavior happening, is lean into it and make sure the path to sharing—and converting on the other side—is optimized.

TikTok is a brilliant example of this.

Of course, they have an advantage over your typical consumer app. If I see a cute cat video, I want my cat-loving friends to see it. So, I share it. But, isn’t that what all social media platforms do?

At face value, yes.

TikTok leverages its users’ social capital to create viral brand equity. Viral brand equity is when, with one action, a user shares something to multiple people in their social network. According to Metcalfe’s law, the value of viral brand equity should equal the square of the number of social network users. For simplicity’s sake, viral brand equity is word-of-mouth marketing, but at scale. Its customer acquisition on steroids, with an exponential growth curve. When someone posts a story, messages a large group, or, even, snaps 15 individual friends at once, this is considered viral brand equity. In theory, the value of distributing that story grew by 225x (15^2) not simply by the value of my 15 friends. This is because those 15 friends are now lending brand equity to TikTok’s platform.

— Justin Hilliard (Ex Product Growth @Meta and Data Scientist @Sonons) via Incentive Theory

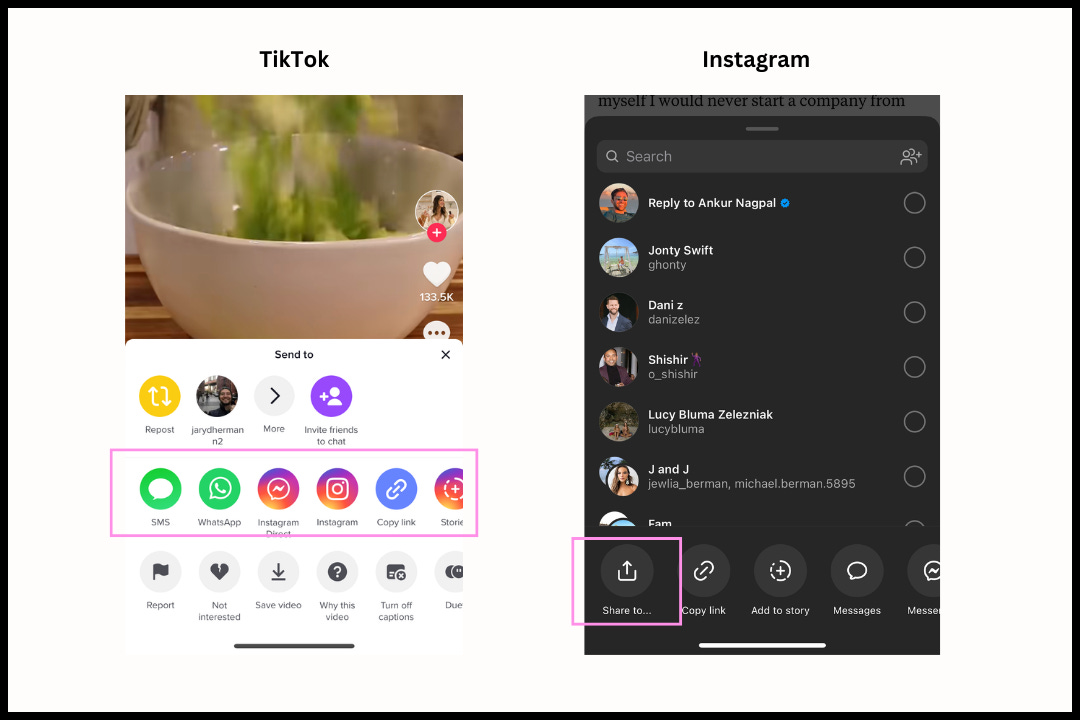

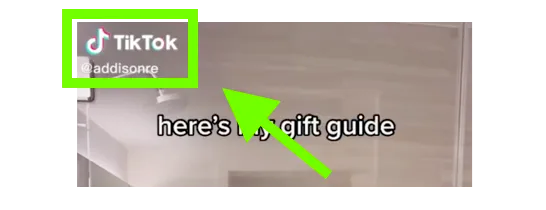

Where TikTok differentiates, is (1) with their extensive share panel that prioritizes one-tap out-of-app sharing, and (2) their watermark that goes along with all shared videos (remember Musical.ly?).

Just to illustrate, here’s TikTok’s share panel vs Instagram’s. Note, the pink marks the real estate dedicated to out-of-app sharing, and TikTok’s panel also scrolls through a ton of options based on the apps you have on your phone.

So, posting a TikTok you like as your Instagram story is (1) in your face, and (2) just a tap away.

And when you share your free “come to TikTok” ad on other surfaces (like your IG story), it’s clearly branded so all your non-TikTok friends get repetitive brand exposure to TikTok. These video logos create billions of additional logo impressions per day.

This is a marketing hack known as ingredient branding.

All in, this leverages their own user actions to generate exponentially more user actions based on concatenating both networks — where out-of-app share impressions provide TikTok with viral brand equity.

AKA—TikTok did a great job at distributing their brand across well-established networks where their users were hanging out.

What’s more, they also tested some clever growth tactics in the early days to aggressively promote content sharing. After two loops of a video (i.e, you enjoy it), the share icon lights up — nudging people toward that out-of-app share panel. And for anyone getting a TikTok link sent to them via SMS, they’d be taken to a mobile-optimized site geared at getting them sucked into more videos before promoting them to download the app.

—

Now, while the next section of growth factors is closely tied to product growth, I think it’s deserving of its own section. In Why Vine Died, we saw how Vine lost focus on the most important side of their platform — the creators. This led to a mass creator exodus.

TikTok, certainly, is not making that mistake.

For Zhang, the creator is everything.

Going deep on creators, and the UGC flywheel

In short, TikTok does a few things to grow the hard side of their platform.

Helping mint and grow new creators (with an engine of meritocracy)

Providing monetization opportunities to creators (by paying ~$0.03 per 1K views)

Enabling creators to experiment and evolve (with new assets and video lengths)

Helping creators build, and engage with, a community (by making comments a social hub)

Together, these forces have made TikTok the best destination for millions of creators around the world to come and build an audience. Which, as we’ll get to in a minute, drives an essential flywheel.

But, of those 4 forces, the only one I want to get into here is the first one, as this is the foundational part of TikTok’s creator strategy and what makes them so unique.

Helping mint and grow new creators with an engine of meritocracy

For starters, TikTok makes content creation super accessible, opening up the opportunity for anyone to whip up a TikTok video and shift from observer to contributor. They do this through their powerful, yet simple, editing toolkit (including clipping, scrubbing, filters, and music) geared toward making content creation a frictionless experience. Remember what Alex Zhu learned before Musical.ly? If creating content requires time, people won’t do it.

With TikTok, all you need is a phone and a good idea and you have a shot at going viral.

Now, “a shot at going viral” on a platform like Instagram, YouTube, or Twitter is near impossible. The Gold Rush for stardom there is over.

But one of TikTok’s most valuable hooks is that anyone does actually stand a shot at being seen. This means there’s a greater window of opportunity for people with compelling content to get popular, fast.

Deliberate product decisions—specifically, algorithmic discovery on the For You page and no need for a follower graph—create space for serendipitous discovery. Meaning, a feed of meritocracy for the app's most talented creators, both new and old. Content feeds don’t just highlight the most liked videos. Often you’ll see videos with just a handful of likes because TikTok thinks it’s within your interest graph. And Alex Zhu, who went on to become Head of Product at TikTok (later, President) likens this phenomenon to creating a new country and giving a greenfield of opportunities to a new class of creators:

In the early stage, building a community from scratch is like discovering a new land. You can give it a name: America. You want people from the existing platforms (i.e. Europe) to migrate to your country. Instagram is Europe. Facebook is Europe.

The economy in Europe is very developed, and in your country there is no economy. How can you attract people to come in? In Europe, the social class is already stabilized. For the average citizen, for citizens of Germany or France, they have almost zero opportunity to go up in the social class. But now you have a new land. America! A.k.a. TikTok.

Initially the majority of the wealth should be distributed to a small number, to make sure new people get rich. These people became a role model for people living in Europe. ‘This is just a normal guy, he went to America, and he became super-rich. I can do the same!’

And then lots of people came to your country, and you grow the population, you grow the economy.

As Casey Newton describes in fewer words:

In previous eras, most of the spoils went to the platform’s earliest adopters - mining value gets harder as the platform ages. TikTok, on the other hand, promotes all content regardless of who made it or how many followers [social capital] they have.

This brings anyone in the social media game an important lesson: enabling and preserving a path from newcomer to middle class is crucial for maintaining a moat. When it becomes too hard to “make it” in established channels, the door opens for new channels to take off.

Additionally, TikTok gave new and existing creators full-service support and educational materials, including weekly content suggestion emails, 1:1 demos with staff, and even IRL events to create a community and drive creator collaboration. This helps warm up new creators, builds their confidence, and gets them to form a content creation habit.

Solving the blank page problem

TikTok also reduces friction for creators by stimulating creativity. I imagine one of the biggest hurdles in getting someone to post their first video, is simply addressing the question, “What should I make?”.

So, similar to Notion’s template strategy, TikTok helps remove this kind of creative obstacle through topic marketing. Basically, they promote and launch hashtags that serve as trending topics or themes on the platform. Then, people go and make their own videos, where they can quickly use existing templates and themes from others.

—

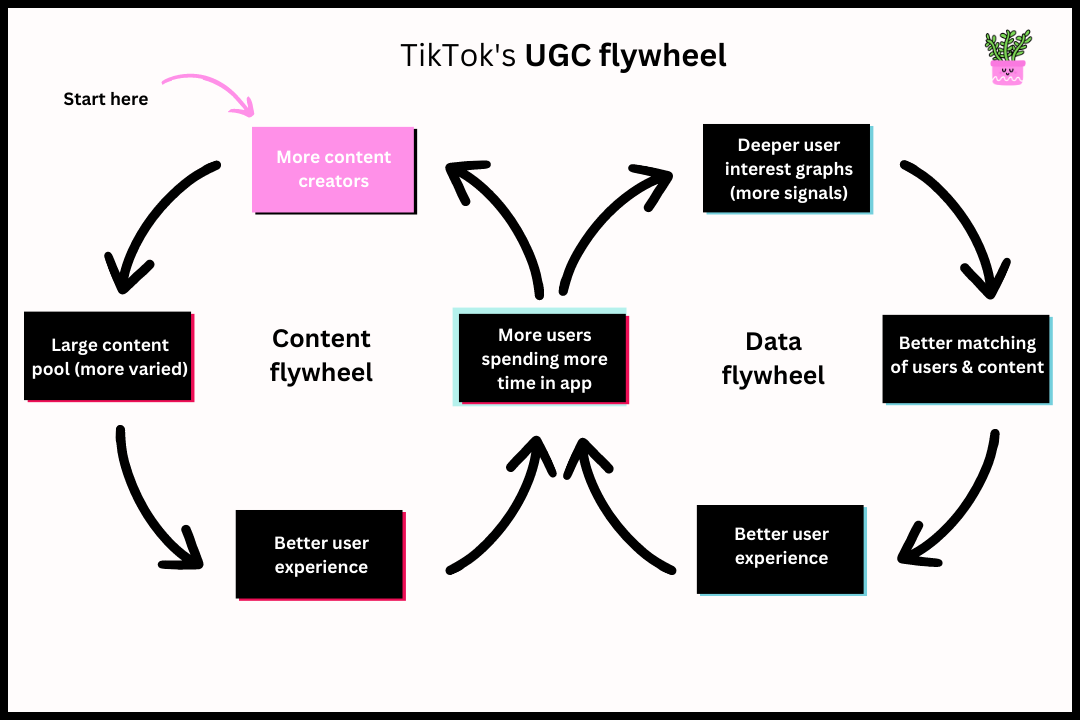

And because of this deep focus on the creator, two interrelated flywheels emerge.👇

TikTok’s virtuous growth loop(s), and data network effects

Simply, the more creators there are, the more (diverse) content there is. This makes the product more valuable to people, filling their feeds with more variable rewards. So, more people spend more time pulling the slot machine. In turn, giving TikTok more data to improve the recommendation engine, thus making the slot machine even more sticky —bringing creators a bigger and more engaged audience. 🔂

And as you can see below, TikTok’s content flywheel drives the data flywheel for their widely deployed, AI-based, middle platform.

This gives rise to a powerful competitive moat: network effects. Or, to be even more specific, two different types of network effects; a standard network effect (the content flywheel), and a data network effect (data flywheel).

Data network effects occur when your product, generally powered by machine learning, becomes smarter as it gets more data from your users. In other words: the more users use your product, the more data they contribute; the more data they contribute, the smarter your product becomes (which can mean anything from core performance improvements to predictions, recommendations, personalization, etc. ); the smarter your product is, the better it serves your users and the more likely they are to come back often and contribute more data – and so on and so forth. Over time, your business becomes deeply and increasingly entrenched, as nobody can serve users as well.

The more automation you build into the loop, the more likely you are to get a flywheel effect going.

— Matt Turck (VC at FirstMark), The Power of Data Network Effects

There are two takeaways here: ⚒️

If you’re building a network-based business, focus on the hard side of the platform. By building features for their creators (the supply side), TikTok drove multiplicative benefits on the consumer (demand) side.

Start thinking about how you can build a data network effect. These are now becoming far more possible for companies much earlier in their development, thanks to the accessibility of Big Data tools (cheaper, faster infrastructure to process large amounts of data) and machine learning/AI (an increasing number of off-the-shelf tools and algorithms to automatically analyze and learn from those large amounts of data. Step 1 is committing to being a data-driven company (if it makes sense). Step 2 is starting to collect good data. (More practical advice here)

And now that we’re talking about network effects here, we just so happen to find our second convenient segue in this post. From growth to defensibility. 👇

Collecting Infinity Stones: TikTok’s 7 Power

In the furiously competitive world of tech startups, where good entrepreneurs tend to think of comparable ideas around the same time and “hot spaces” get crowded quickly with well-funded hopefuls, competitive moats matter more than ever. Ideally, as your startup scales, you want to not only be able to defend yourself against competitors, but actually find it increasingly easier to break away from them, making your business more and more unassailable and leading to a “winner take all” dynamic.

— Matt Turck

Now, there’re a few different frameworks for thinking about competitive moats.

A favorite of mine is Hamilton Helmer’s, from his book, “7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy”. He argues that there are seven moats that a business can leverage to make itself “enduringly valuable.”

The book has a bunch of case studies that show us companies that use 1/2 of these moats to sustain their advantages.

Netflix takes advantage of (1) scale economies and (2) counter positioning.

Facebook and LinkedIn build (3) network effects.

Oracle has high (4) switching costs.

Tiffany’s has a powerful (5) brand.

Pixar’s “Brain Trust” is a (6) cornered resource.

Toyota’s Toyota Production System demonstrates (7) process power.

TikTok boasts all 7.

Here’s a breakdown of what they are, and why TikTok has them. 👇

Scale Economies. 📉

WHAT IT IS: As your business gets bigger your unit costs go down.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: As their user base has gotten bigger, there’s more social capital going around (WoM, sharing), driving down their customer acquisition costs. Also, their AI product compounds over time, driving more ad sales and better engagement.

Switching costs. 😓

WHAT IT IS: The harder and more costly it is to leave your product, the higher the switching costs are.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: As creators’ audiences get bigger, there’s more of a reason for them to stay. Walking away from money on the table is hard.

Network effects. 🕸️

WHAT IT IS: A flywheel-type situation where your product becomes more valuable when more people use it.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: We just saw how they have a standard network effect and a data network effect.

Cornered resource 💎

WHAT IT IS: You have IP, like a patent or copyright.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: TikTok is powered by ByteDance’s ever-improving, proprietary, AI. The more people that use ByteDance’s widely available consumer products, the better it becomes — making this secret audience extremely defensible.

Process power ⚡

WHAT IT IS: You have some type of internal organization or activity that makes you extremely efficient.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: ByteDance’s AI is available in their shared middle layer. So, with each new product they launch, it gets to piggyback on essential infrastructure. This brings speed, which is a huge advantage.

Counter-positioning 🛡️

WHAT IT IS: You’re doing something in your business model that incumbent competitors can’t copy. If they did, they’d risk cannibalizing their existing business

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: Compared to all other social networks, TikTok is an “anti-social” network, as they don’t need any follower/friend graph to be valuable. Again, this is great for their engine of meritocracy.

Brand 😍

WHAT IT IS: You’ve built a recognizable and trusted brand in your market.

WHY TIKTOK HAS IT: TikTok is a household name now. If someone doesn’t use it, it’s most likely not because they don’t know about it. This opens up the debate of whether TikTok/ByteDance is trusted or not. 👇

In the startup-verse, having this many of the 7 powers is like wielding the Infinity Gauntlet with all 5 stones. You’re near unstoppable, and being taken out by competition is increasingly difficult.

Unfortunately, Uncle Sam isn’t too happy about a Chinese company having it. And with a snap of their fingers, they can make half* of TikTok go away.

This takes us to our steamy, and important, conclusion. 🤔

[*FYI: Not quite half, but saying 113M users didn’t quite finish my Marvel bit as nicely.]

The Endgame: The “RESTRICT Act”, banning TikTok for Americans, and the future of the Internet

As you more than likely know, TikTok’s future in America is touch-and-go.

But it’s not just TikTok’s fate in the balance. It’s privacy on the Internet.

Let’s start with a quick primer.

What’s the situation? A brief recap.

Despite TikTok’s global success, their growth path in the US has been scattered with a number of accusations and regulatory measures. Why?

To put a complicated issue simply, the US government is worried that because TikTok is a Chinese company, they are subsequently “controlled by China”. Meaning, people are worried ByteDance may be forced by the Chinese government to surveil Americans or try to influence them by promoting pro-China or anti-US content. As the Time’s reports.

The case against TikTok isn’t hard to make. The heads of the F.B.I. and our spy agencies fear that the Chinese government will force TikTok’s owner, ByteDance, to hand over the extensive personal information of the app’s American users or demand that it push disinformation.

In fact, China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law requires Chinese companies to furnish any customer information relevant to China’s national security. TikTok collects astonishing amounts of user information, more than some other popular social media apps. There’s no evidence that ByteDance has ever turned over this information to the Chinese government. Yet in an episode that revealed the possibility of future government interference, ByteDance admitted in December that it had fired some China- and U.S.-based employees for wrongfully snooping on Americans’ private information, including that of journalists, collected through TikTok.

Although it hasn’t happened yet, it’s easy to see how China could commandeer the powerfully influential app to affect elections or manipulate public opinion, with especially pernicious effects in a time of crisis. Two out of three American teenagers have used TikTok, so disinformation on the app could be particularly potent for that impressionable audience. There’s no better evidence of why a government might fear the app’s insidious nature than the fact that TikTok is banned in China itself. Instead, the Chinese government lets ByteDance use a limited domestic version of the app that’s explicitly subject to state censorship.

— Glenn S. Gerstell, The Problem With Taking TikTok Away From Americans

That’s why Trump tried to shut it down, leading to TikTok spending $1.5B to safeguard Americans' data, as well as keeping American users’ data on Oracle servers.

Except, ByteDance still stores their own backups of that data…so that’s basically a moot point.

Which brings us to today, where the Biden administration is continuing the push Trump started and looking to force ByteDance’s hand in divesting TikTok.

So far though, only government workers have had the app banned. But lawmakers aren’t stopping there. And alarmingly, there is actually bipartisan support for something for a change.

At a glance, these are the solutions being presented:

What the US government is pushing for

Much stricter data control policies. American executives would control content and user data; ensuring that data isn’t siphoned off to China and preventing China from censoring or manipulating information on the platform.

Selling TikTok to a US company. The next outcome would be for ByteDance to sell the app to an American company. ByteDance has resisted this option.

An outright ban of TikTok in the US.

So, if option C happens; what are the consequences?

The problem with banning TikTok

Geopolitical problems

Things are not exactly going well between the US and China right now.

And while there’s been plenty of debate about decoupling the US. and Chinese economies, we haven’t really done anything aside from some restrictions on Hauwei and DJI drones.

Kicking a huge social media company used by almost a third of Americans, one associated with the everyday expression of political and personal views, could easily invite retaliation. Not to mention, the last thing the US needs is a greater strain on our deteriorating relationship with China, and anything than could encourage any lash out.

We’re already antagonizing China in various ways, with the US’s fear of losing power. This is not to say banning TikTok will go down in history as the start of WW3…but let’s just cool it.

As the same Time’s piece noted above goes on to say:

The recent limited bans on TikTok are mostly an effective way for politicians to sound tough on China. The House of Representatives has just established a select committee to investigate the strategic challenges posed by China to America’s economy generally and especially to its tech industry. There’s no dispute that China represents a genuine threat in many ways — but the danger is that political winds will push us to do something bold about TikTok without thinking through the long-term consequences.

And the ban may have geopolitical implications beyond China:

Increased scrutiny and the potential of a ban also could raise a tit-for-tat that leads other countries to ban U.S.-based apps and businesses, out of fear the U.S. government may have access to data they collect. It also might deter foreign companies from expanding in America, if they also do business in China, out of concerns they may get either caught in a tug of war or find themselves banned.

Then there’s the even bigger concern with a TikTok ban.

Tapering free speech

TikTok is a platform for many people to express political views and stay informed about what’s going on in the world. Even TikTok users who just watch videos without posting their own content have a First Amendment right to receive information. That right, according to standing Supreme Court ruling, even extends to propaganda from a foreign government.

So, by taking TikTok away we’re getting into First Amendment territory. As US TODAY notes:

Banning an app, however, could raise significant questions about the First Amendment rights of TikTok’s American users and affect far more than the ability to take part in the latest dance craze.

The banning of an app removes an opportunity for communication and expression for millions of American users. [And] TikTok bans dramatically expand the government’s ability to control what apps and technologies Americans can choose to use to communicate. Further, bans create consequences not just for the companies themselves, but also for users who violate the bans.

The ACLU, for example, has expressed concerns about the free speech and additional civil liberties implications of government bans by pointing out how it could set a dangerous precedent for the government interfering with what apps Americans may use to express themselves and communicate with others.

Reuters adds:

Sixteen public interest groups, including the ACLU, the Authors Guild and the Knight First Amendment Institute issued a letter to Congress last week, warning that a wholesale ban on TikTok was an “ill-advised, blanket approach that would impair free speech and set a troubling precedent.”

But lawmakers, with Democratic and Republican buy-in, are still pushing for a bill (Senate Bill 686) to go through.

It’s called The Restricting the Emergence of Security Threats that Risk Information and Communications Technology.

Clearly named by some smart folks to land on the acronym: RESTRICT.

And while they peddle that it’s just about banning TikTok, unfortunately, it’s just not true.

The word TikTok is not even mentioned in the bill once.

So, very importantly, this is not just about TikTok. The bill— which has been dubbed “The Patriot Act 2.0”— has much broader ramifications. It stirs big questions like “How open should the Internet really be?” and “How much state involvement should there be in Internet content?”.

Democratic Internet has always answered, “very open” and “no involvement”. But things could be at risk of changing. 👇

The “RESTRICT Act”, and what it means for Internet privacy

The RESTRICT Act is essentially government nationalization of the Internet and it goes after everything that contributes to individual people’s freedom and safety online.

Basically, if the US has beef with another country, they can ban any apps that come into the US from them. Transparency into the process behind these bans is outside of any Freedom of Information Act request, and it allows the monitoring of anyone in the US using the Internet no matter how they access it. And if you use a VPN to access content that is blocked by a ban, you could be labeled a threat to national security and face up to 20 years in federal prison, or be fined up to $1M.

Yes, it would allow the banning of TikTok. But that’s only because it allows for the banning of almost anything that has a tie to a foreign country. Citing it as merely a TikTok ban buries the much more damning (and vague) language of the bill and makes it seem frivolous for anyone who doesn’t care about losing some cat videos. But, it affects everyone in the US and if it passes, we’re opening ourselves up to new possibilities of surveillance, censorship, and control.

Yikes.

Sounds a bit like China and Russia’s Internet, no?

Here’s what people are saying about it: 👇

[Video, thread, and comments continue here.]

Food for thought. In the meantime, I’m off to pull the slot machine.

And that, folks, is a wrap on our ByteDance / TikTok analysis. 🫡

As always, thank you so much for reading my newsletter. I really hope you enjoyed this piece and learned something new. If you did, I’d be very grateful if you:

Subscribed if you’re new here

Hit the little heart button below

Give this post a share

Until next time.

— Jaryd ✌️

on the slot machine analogy - do you think it is optimal to let users hit jackpot 100% of time? What are the merits of picking a lower hit rate (in the system’s eyes) e.g. 98%? Also what are the merits from a psychology perspective (if any) of a user not being satisfied on some swipes?