🌱 5-Bit Fridays: The new mechanics of brands, ignore your power users, the downside of LTV/CAV, good metrics, and 9 mental models to change your thinking

#27

👋 Welcome to this week’s edition of 5-Bit Fridays. Your weekly roundup of 5 snackable—and actionable—insights from the best-in-tech, bringing you concrete advice on how to build and grow a product.

Happy Friday, friends 🍻

In this week’s news, apparently, the streaming wars are over, and gaming is looking like media’s next big thing. Also, while ChatGPT just became an IOS app, OpenAI’s Sam Altman urges Uncle Sam for more AI regulation. Which, if we’re being honest, is kind of like a parent taking their kid to the park, and then telling a park ranger that their kid bites and should be monitored. Hmm.

In more local news, this week I teamed up with the product and growth legend,

, to tackle a deep dive on Klarna and the BNPL industry. This was a ton of fun. In case you missed it…👇How Klarna Grows: Building The Shopping Destination of the Future

A primer on the $260B Buy Now Pay Later market, and a deep dive into how Klarna grew from 0 to 150M customers and is disrupting the $8 trillion credit industry.

Onto today’s post…

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

Brands, same importance, entirely new mechanics

Listen to your users, and ignore them too

4 reasons why LTV/CAC is not a great metric for early startups, and what to use instead

How do you define a good metric?

9 mental models to change the way you think, illustrated

Small ask: If you learn something new today, consider liking this post or just telling your friends about HTG. I’d be incredibly grateful, as it helps more people discover my writing.

Alrighty. Let’s get to it.

Brands, same importance, entirely new mechanics

Last week we spoke about seismic shifts in Gen Z behavior, like sustainability, mental health, and the rise of digitally native jobs. This week, we’re looking at seismic shifts happening in the world of brands.

Earlier this year,

—the current Chief Strategy Officer (and former Chief Product Officer) at Adobe, and ex-founder of Behance— wrote a truly fascinating piece on the larger trends he’s been observing with brands.It’s a real peak behind the curtain. And since we are all either consumers of brands or builders of brands (and brands ourselves), these forecasts and their implications are relevant to all of us.

The vast majority of the premium we pay for most things is for “the story.” Those $120 Nike shoes are probably ~$6 for the materials and labor, and $114 for the virtual good (the story). Despite all of the effort to commoditize products or manufacture soulless white-labels, brands with story, the ultimate virtual good, continue to command a premium.

As consumers, we want to buy narratives whether we admit it or not. With every purchase we exercise our values, interests, and affiliations. But the mechanics of brand creation and growth are changing. What was once predominantly physical with digital afterthoughts is increasingly virtual and natively digital.

— Scott Belsky

Okay, so what are these new mechanics Scott’s been seeing, and what are the implications?

Here’s the high-level need-to-know, with my favorite excerpts from Scott: 💡

Brand story is increasingly the differentiation, while other moats (like logistics, distribution, sponsorships, etc) are details. “Brands are the margin in a world that can otherwise be boiled down to commoditized atoms and bits. The creation of brand value is where culture, psychology, and technology all overlap. Great brands have always started with the story, but the major operating moats like manufacturing, marketing, selling, shipping, and customer services that were once differentiating are increasingly available as simple SaaS solutions. As a result, the top of funnel for new brands has been opened to all.”

Data sharing efforts, like Shopify’s new Data Cooperative, will provide some of the big brand benefits to small and emerging brands. “There has been some talk of Shopify allowing brands (and especially the long tail of ‘microbrands’) to share customer profiles to reach new customers and better service existing customers. ‘Shopify Audiences’ is a data sharing co-op between Shopify merchants. Shopify serves as the official custodian of this shared data pool, and participants contribute their existing customer data anonymously into a shared data pool. As Shopify learns from this shared data, they are able to determine customer personas and buyer profiles of Shopify customers, and then use this data to better match audiences with specific Shopify brands”

DTC brands will migrate to traditional retail channels en masse. “What was once the pride of DTC brands (avoiding the constraints and margin degradation of traditional retail channels like Target) is becoming not only a preference and growth vector but also a desperation. This is a growing trend as the cost of customer acquisition on digital skyrockets given changing data privacy laws and other factors reducing conversion. Modern direct-to-consumer brands are being seduced by the efficiency and predictability of shelf space and chain-wide wholesale partnerships.”

Brands shift from traditional advertising to community building. “People ultimately value a brand based on who else is involved - that our purchases are, to some extent, entry points to an imaginary membership or community. Over the years, I’ve come to agree that every brand is, to some extent, a cultural flex of sorts. The communities we (often subconsciously) join as we associate ourselves with brands will become more explicit as our purchases are increasingly part of our online identity and brands offer more ways to connect us.”

Brands natively integrate “renewed” inventory alongside new merchandise. “I’ve heard the term ‘resale as a service’ (and even the new acronym RaaS) in a few conversations lately. I expect we’ll see many more established brands offering renewed inventory as an alternative to new inventory, and ultimately capturing a percentage of sales without any inventory risk, production costs, or fulfillment responsibilities.”

Modern brands need the plumbing to “think and act in real-time” for marketing opportunities. “Remember when the lights went out during the Super Bowl in 2013 and, seemingly instantly, Oreo’s social accounts posted a series of ‘You can still dunk in the dark’ ads that went viral? The next day, Huffington Post noted ‘one of the most buzz-worthy ads of the Super Bowl on Sunday wasn’t even a commercial – it was a mere tweet from Oreo during the blackout.’ At this moment, I realized that the days of classic marketing (briefs, review cycles, big design teams coordinating, etc) were over. In the modern digital life, wit and timing matter. Beyond the plumbing, big companies must modernize their marketing practices and embrace the real-time nature of brand building.”

Super interesting stuff. I also very recently came across Scott’s Substack (where I think the best independent writing in the world is happening). His newsletter is all about the latest advances in tech, shifts in culture, and evolution in the art and science of product design and building teams. For more analyses like this one on brands, check out

Listen to your users, and ignore them too

You’ve heard the advice…listen to your customers.

And that’s absolutely right. It’s product management and founder 101 stuff. The more you listen, the closer you are to their problems and the more, as Y Combinator says, you’ll “build something people want”.

But…

Just like how working out and exercising is good for you — if you listen to this guy's advice in the gym…

Well, you get it. You’ll go down a path of doing all the wrong things.

AKA — not all workout advice is equal.

The exact same thing is true for listening to your customers.

As Sarah Tavel (GP at Benchmark, ex-GP at Greylock, and former PM at Pinterest) describes:

Your loudest users — the users who complain when you ship something they don’t like, and post in your Facebook Group their feature requests, are a blessing and a curse. Without them, you wouldn’t have a company. But to reach your next 100m users, you need to be willing to ignore them.

Here’s the trick: Your loudest users don’t represent all your users, and they definitely don’t represent your future users. They are your power users, your users who best understand your product the way it is now. This creates two biases:

They’ve gotten used to using the product the way it is, so they don’t want things to change.

They inevitably request power-user features — features that increase the complexity of your product for everyone but only get used by a minority of users.

To add to that, it’s not just power users that you need to be cautious about listening too heavily to. You may have folks eagerly giving you feedback that are not yet power users, but, are also not your ideal customer profile right now. For instance, listening to a big enterprise could be very appealing, but if you’re early stage and focused on the other end of the market, this could prematurely take you down a path of building for the wrong audience.

Anyway, let’s focus on the first camp — loud power users. According to Sarah, this is how those two biases can lead you down the wrong path, that once taken, becomes hard to back peddle from:

1) Not wanting things to change

The Innovators Dilemma reminds companies that over time, if they want to be enduringly valuable, they need to be prepared to disrupt themselves.

Perhaps you recall when Facebook rolled out their now iconic newsfeed product back in 2006. I don’t personally remember because I didn’t care in grade 6, but I know there was an overwhelmingly negative response and Facebook had to deal with a lot of backlash.

Well, that “feature” became their core product.

If Zuckerberg had let that small minority of power users dictate what was best for the majority, Facebook would certainly not have grown into the company they are today.

I am sure it was hard to ignore a vocal minority and the related press. But, Facebook dug into broader data, saw behavior that indicated the opposite of what people were upset about and stuck to their guns.

Of course, this is an extreme. But as Sarah points out, these things happen regularly on a smaller and more relatable scale:

Want to simplify a core product flow? Your users don’t care if a redesigned flow takes out two steps — they’re used to those two steps! Want to simplify the product by removing a little-used feature? But that’s my favorite feature!

It takes courage to make these changes — you don’t want to irritate your best users, but you need to keep that next 100m users in mind who can’t tell you what they want. The key is to listen to what the data says, communicate to your users, and be prepared to ignore your vocal minority if the data points you in a different direction.

2) Building power user features

If you build every feature your users ask for, you’ll end up with a very small, highly engaged user base.

First, user requests operate within the local maxima that your product sits in. Remember the famous (likely made-up) Ford quote of customers asking for a faster horse? That’s your users.

Inevitably, they’ll ask for features that add complexity to the product, making it harder to understand for a new person who’s trying it out for the first time. Sometimes this additional complexity is worth it, but more often it’s not. Whenever we built the #1 most requested feature of our existing users [at Pinterest], it got used by <5% of users, so it really needs to be a game changer for those <5%. And remember: it’s a lot easier to add features than it is to take them away. So be careful with what you add

The other problem is that the features they request are often band-aids on symptoms, not real solutions. As an example, one of the most requested features while I was at Pinterest was the ability to re-arrange pins. You can imagine the use case: having to always scroll down to the bottom of a board to find your favorite recipe. If only you could drag that pin to be on the top of your board! But this isn’t the best solution

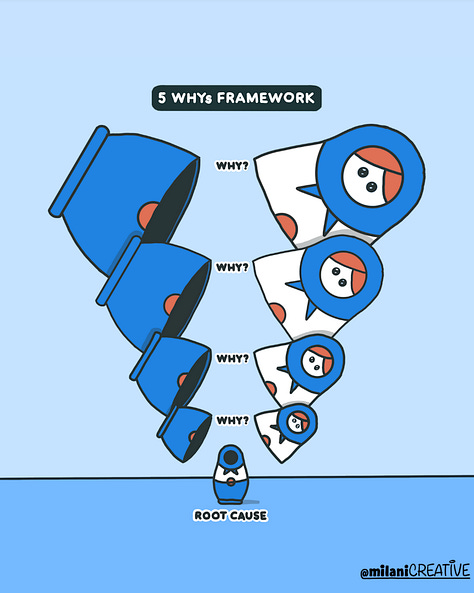

Power users request power-user features. Re-arranging pins is the type of feature only a very small percentage of committed users would use. When you dig deeper, the request is a symptom of a root cause — it’s hard to find pins you’re looking for.

In other words, our job as PMs and founders is not to build the features users ask for, it’s to ask the right questions that help us find the scalable solution — the solution that the majority of users will do.

Listening to this power user would mean you end up with…I don’t even know what. Is she training to be a Kangaroo or something? 🤔

Anywaaay…onwards.

4 reasons why LTV/CAC is not a great metric for early startups, and what to use instead

I recently stumbled on Jeff Chang’s blog, and I thought one of his articles presented an interesting perspective on a common growth metric. As Jeff wrote:

Lifetime customer value over customer acquisition cost is one of the primary metrics that companies use to measure ad spend efficiency. Intuitively, it makes sense as a metric. For every dollar you spend, you want to make back more than a dollar. It's a useful metric for large companies that spend millions because a small improvement in LTV/CAC results in significantly more profit. However, there are many reasons why for startups, it's not as useful of a metric

Let’s take a look at those reasons, as well as what alternative metric he proposes.

Reason 1: Startups don't live forever. “When calculating LTV, usually companies assume a user will retain between 3-10 years. However, a lot of startups don't have 3-10 years of runway to recuperate their ad spend loss. So, the lifetime of the user is capped by the lifetime of the startup and the "effective" LTV is lower than what's projected.”

Reason 2: CAC for the first 100 users is different from next 1000 users. If you put dollars into a campaign for a specific audience set, in the beginning, you’ll enjoy better returns on your ad spend. But, this result does not extrapolate to bigger budgets. Meaning, “As you scale your ads, your ROAS generally goes down to a point where it won’t be profitable past a certain point. Various factors are in play here, for example, saturation of audience and how ad platforms usually find the lowest cost users first. So, it doesn't make sense to run a small test, calculate a LTV/CAC, and assume that will apply for a larger spend.”

Reason 3: Startups likely don't have enough data to accurately calculate LTV/CAC. As

has written extensively about in his CLV series, there are a lot of variables involved to get accurate LTV and CAC numbers. For instance, retention data. But, if you’re just a few months old, you don’t really have anything significant there yet. Also, as Jeff says, “Products change a lot over a year for startups so cohorts now may not behave like cohorts a year ago. So, most startups don’t have the data needed to accurately model LTV.”Reason 4: It's not worth a startup's time to calculate LTV/CAC correctly. “To get an accurate LTV/CAC number, it requires significant work and usually an analyst or data scientist. It also requires segmenting your users by different cuts because different types of users have different LTV and CAC values. Then, you have to create an accurate model of how long an average user of that segment retains and spends. Finally, you have to predict the CAC for just that segment which is not that simple either. The large amount of time spent calculating an accurate LTV/CAC is probably better spent growing the company in other ways.”

That’s why Jeff thinks LTV/CAV is problematic for early-stage startups. Instead, he poises that payback period is a better metric. 👇

As the name nearly perfectly describes, payback period is the time it takes to recuperate the cost of ad spending through revenue. Once you’ve made your money back, the rest is profit.

So, how do you calculate it, and why would it be better?

Calculating it accurately is also slightly complex because it involves predicting revenue over time, and may need to be done in user segments. Instead of spending significant time trying to get the exact payback period, my advice to early stage startups is that it should be very obvious if your ads are profitable, or they aren't worth running and optimizing at early stages of a startup. This means your payback period is 0 or close to 0.

For example, if you spend $1000 on ads which result in subscriptions netting $1000 in the first month, that's obviously a great payback period and you should keep spending. If you spent $1000 on ads which result in $500 in the first month, $300 in the second month, $150 in the third month, and that's all the data you have, then it's unclear how long the payback period is. It may or may not be profitable, but we can be pretty confident it's not super profitable. So, the opportunity cost of shutting down these ads is not high, and I would not recommend focusing resources on optimizing these ads in this case.

To the marketers, I’d be curious to know what you think of this advice. Drop your thoughts in the comments.

Speaking of metrics…

How do you define a good metric?

We all know the importance of focusing on metrics and being data-driven.

Better decisions are made with more data. Better cases can be made based on clearer evidence of what’s working or not, removing ego and bias. And it removes reliance on intuition and guessing around what should be built and prioritized.

Everyone feels better with data. Data is good.

And data is even better when you’re using good metrics. What’s a good metric, you ask?

Who better to tell us than Sanjeev — my favorite product management cultural observer and commentator?

Jokes aside though. What happens when we’re tracking the wrong thing? What happens when we misinterpret the data or rely on too little data to make the right decisions?

Simply put, not all metrics are created equal.

In a great post by

for , he outlines the 4 components of a good metric.

A good metric is understandable: These days, you can track so much data. You instrument your entire application to monitor everything people are doing. You can get access to competitive data (in some cases). You can segment users or customers into different groups based on behaviour. And so on. The instinct is to track as much as possible, which is OK, but it does tend to complicate things.

So the first thing you need to do is ensure the metrics you’re tracking are easy to understand. I’ve always thought of analytics as a “common language” that everyone should be able to speak because it’ll help everyone within your organization know what’s going on and collectively make better choices. So do your best to simplify the metrics and not overwhelm users.

A good metric is comparative: Metrics often represent a single point in time. They give you a snapshot of what’s happening at the moment. But that’s never the whole story. For example, if I tell you that I have 10,000 active users in my application, it’s difficult to know if that’s good or bad. If I tell you that last month I had 1,000 active users, comparing last month to this month, it looks quite good! I’ve seen a 10x increase in active users.

A good metric is typically comparative over a period of time. This is where we start to dig into cohort analysis and why it’s so important to measure progress over time as you make changes.

A good metric is a ratio or rate: Comparing numbers over time is helpful, but it may still not tell the whole story. In the example above, let’s say that last month I had 1,000 active users out of 5,000 signups, so I had 20% become active users. This month I have 10,000 active users (which is 10x last month), but I actually had 200,000 signups, which means I only turned 5% of my users into active users. (I know these numbers are simple, but hopefully, you get the point.)

Ratios or rates tend to be more revealing than whole numbers. In my simple example above, I somehow managed to acquire a lot more users, but very few of them became active. While I’m happy with a 10x increase in active users, something is not quite working regarding the users I’m acquiring.

When evaluating the metrics you’re focused on, they should be ratios or rates, which are inherently comparative.

A good metric is behaviour changing: This is the most important aspect of a good metric. It leads to what we described in Lean Analytics as the “Golden Rule of Metrics” - if a metric won’t change how you behave, it’s a bad metric.

The key to being a successful product manager is being able to narrow your focus on the few key metrics that actually matter.

And you know they matter because no matter whether they go up, down, or stay the same, you’re going to take action.

To go deeper on this, Ben’s post continues with Understanding the different types of metrics

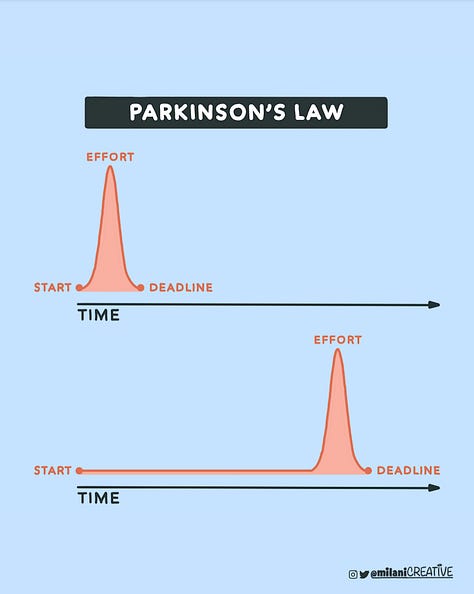

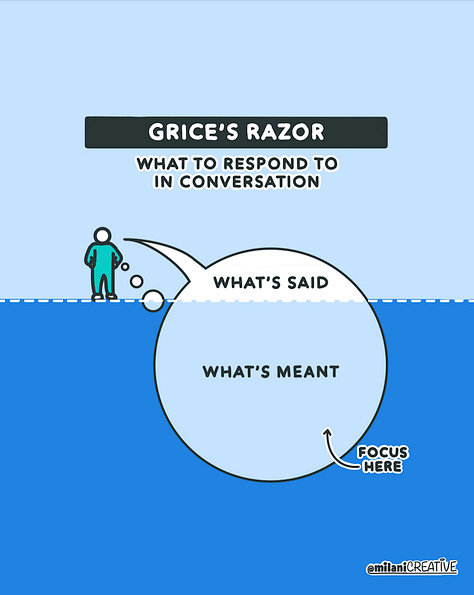

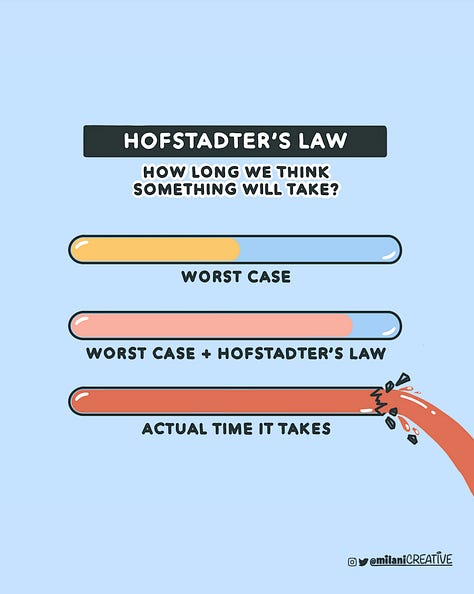

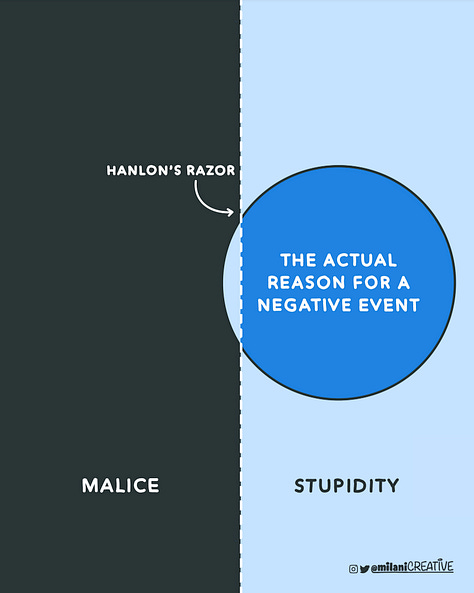

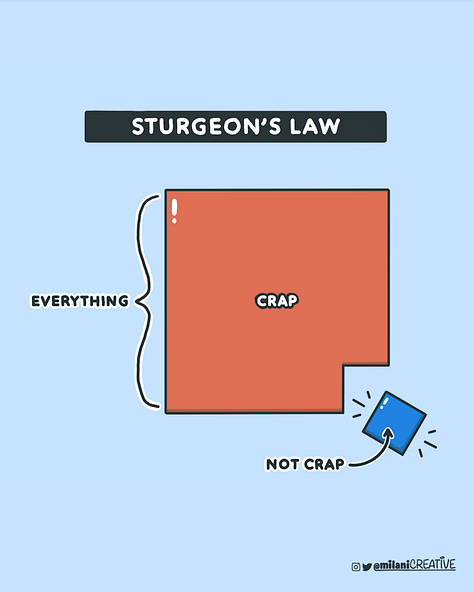

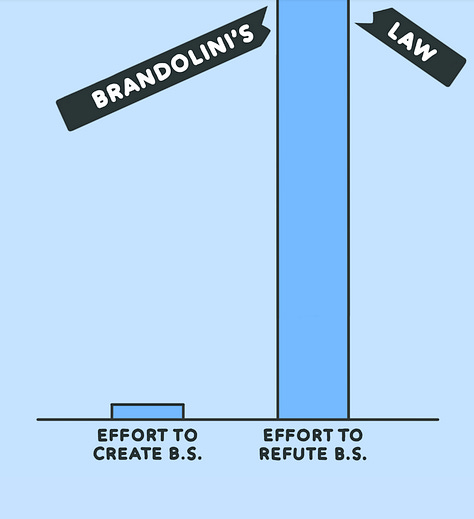

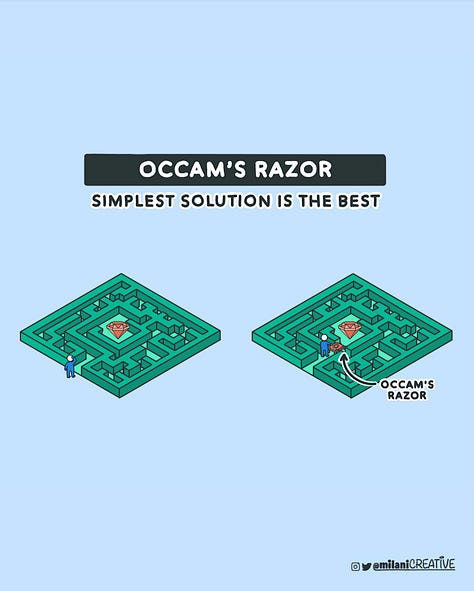

9 mental models to change the way you think, illustrated

I’m a visual thinker. So, when I came across Pejman (PJ) Milani’s work on LinkedIn, I got really excited.

PJ uses beautiful visuals to simplify complexity, and honestly, his work speaks for itself. Just take a look at how he explains 9 mental models. (Tap/click on the first image to expand).

If you enjoyed that, definitely check out PJ’s I.D.E.A Visual Newsletter.

🌱 And now, byte on this if you have time 🧠

TL;DR:

With the markets returning to focus on profitability, valuations are no longer linked to growth at all costs.

If the past recipe for a premium valuation was three parts growth, one part profitability, the recipe seems to have shifted to at least two parts growth, two parts profitability.

Cash burn has become a “dirty word”. But perhaps we were just overdue in reassessing what “good” cash burn looks like.

In a fantastic deep dive,

goes through “The Art of Burning Cash” and more.READ: Burning Bad: Cash burn, cash runway and valuation

And that’s everything for this week.

As always, thank you so much for reading. If you learned anything new, consider tapping the share button below, or telling anyone you think would find my stuff valuable. Thank you.🙏

Have a wonderful weekend, and I’ll see you next time.

— Jaryd✌️

Genius. So happy I found this.

This is your best issue so far wow