5-Bit Friday’s (#16): Snackable insights, frameworks, and ideas from the best in tech

On: “Non-Goals” and building a "Product Strategy Stack", Becoming a Camel, The Elephant in the room, Growth inflections, and Choosing the right game to play at a startup

Hi, I’m Jaryd. 👋 I write in-depth analyses on the growth of popular companies, including their early strategies, current tactics, and actionable business-building lessons we can learn from them.

Plus, every Friday I bring you summarized insights, frameworks, and ideas from best-in-class experts to help us become better builders.

Happy Friday, friends! 🍻

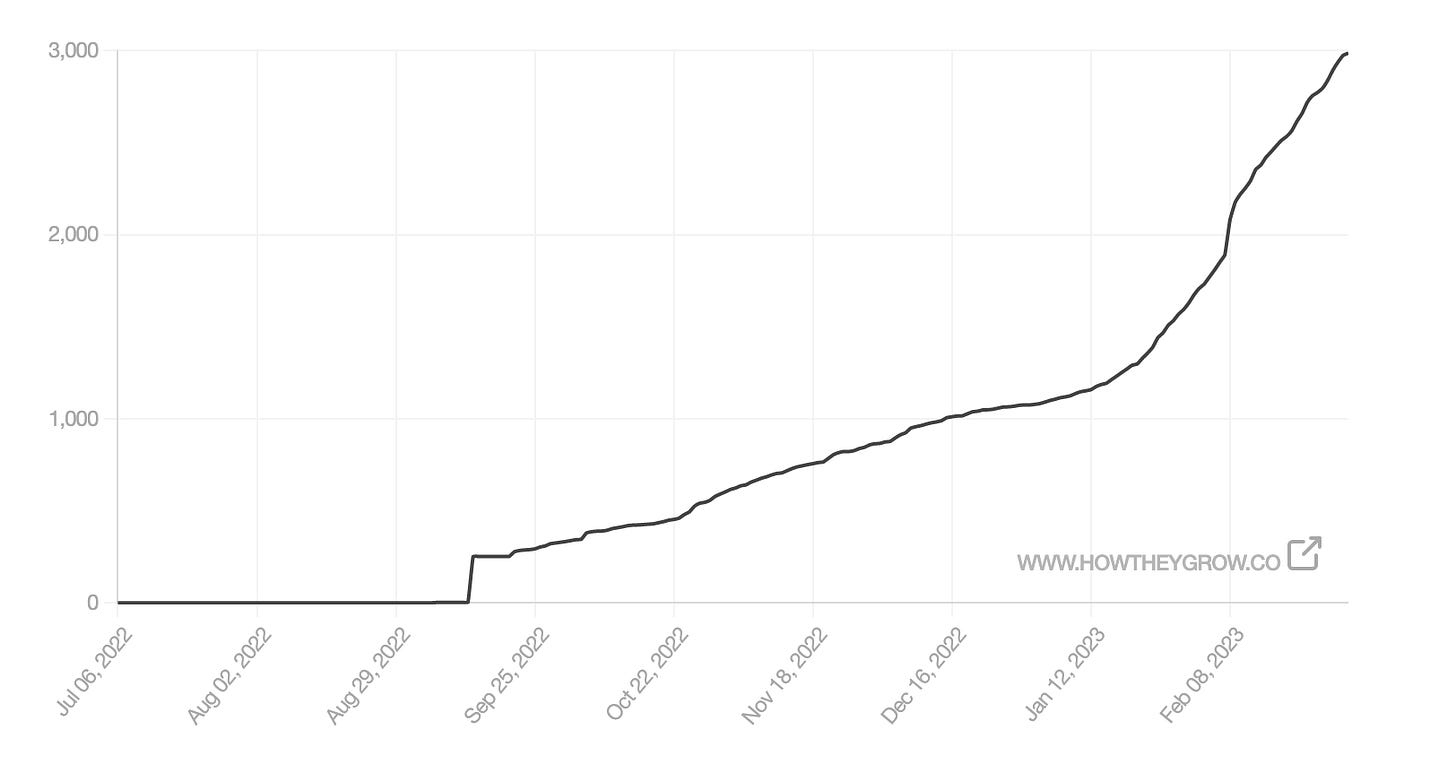

I hope you’ve all had a lovely week. Before getting started today, some quick build in public updates. This morning, we’re just 7 subs away from crossing the 3K subscriber mark, growing 78% in Feb. 🤯

Truly, I’m blown away. Thank you so much for being here, sharing HTG, and the awesome DMs you’ve sent letting me know you’re getting value out of my writing. It means a lot, and I’m very excited to see How This Newsletter Grows. 🙏

Also, big shoutout to @volodarik for the advice and help with my first Twitter thread earlier this week. Definitely a noob on that front, so, thank you.

And lastly, I’d love your thoughts on something. So far, we’ve focused on how some amazing companies are succeeding, extracting repeatable lessons for us to use in our own endeavors. But, that paints just one side of the story. 🤔 What about all the once high-flying companies that closed their doors? Why did they fail, and what lessons are there to be learnt?

I think it’s valuable to look at growth from both angles. So, I’ve been toying with an idea for a new series to balance it out, Why They Died…

And if you’re a yes and have any suggestions on companies you’d like me to dig into…feel free to drop me a message: hermannjaryd@gmail.com

Things worth checking out 😎

A new app to make thinking and writing visual. Scrintal is a visual-first knowledge management tool where you can brainstorm, develop ideas and have the ultimate overview effect. If you’re a visual thinker like me, you can check it out here and join their waitlist for a freemium account. [Sponsored]

And with that….

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

Set “Non-Goals” and build a Product Strategy Stack — Lessons for product leaders

Why startups should become ‘Camels’ – not Unicorns

The Elephant in the room: The myth of exponential hyper-growth

What causes growth inflections

Choosing the right game to play at a startup

Set “Non-Goals” and build a Product Strategy Stack — Lessons for product leaders

Product strategy is the connective tissue between what a product team is doing day-to-day and the company’s ambition.

— Ravi Mehta, Product Leader (Ex Tripadvisor & Tinder), Executive Resident at Reforge

In an interview between Ravi and First Round Capital, he dives deep into product strategy, starting with the most common disconnect between the goals of a business and what product teams actually work on day-to-day.

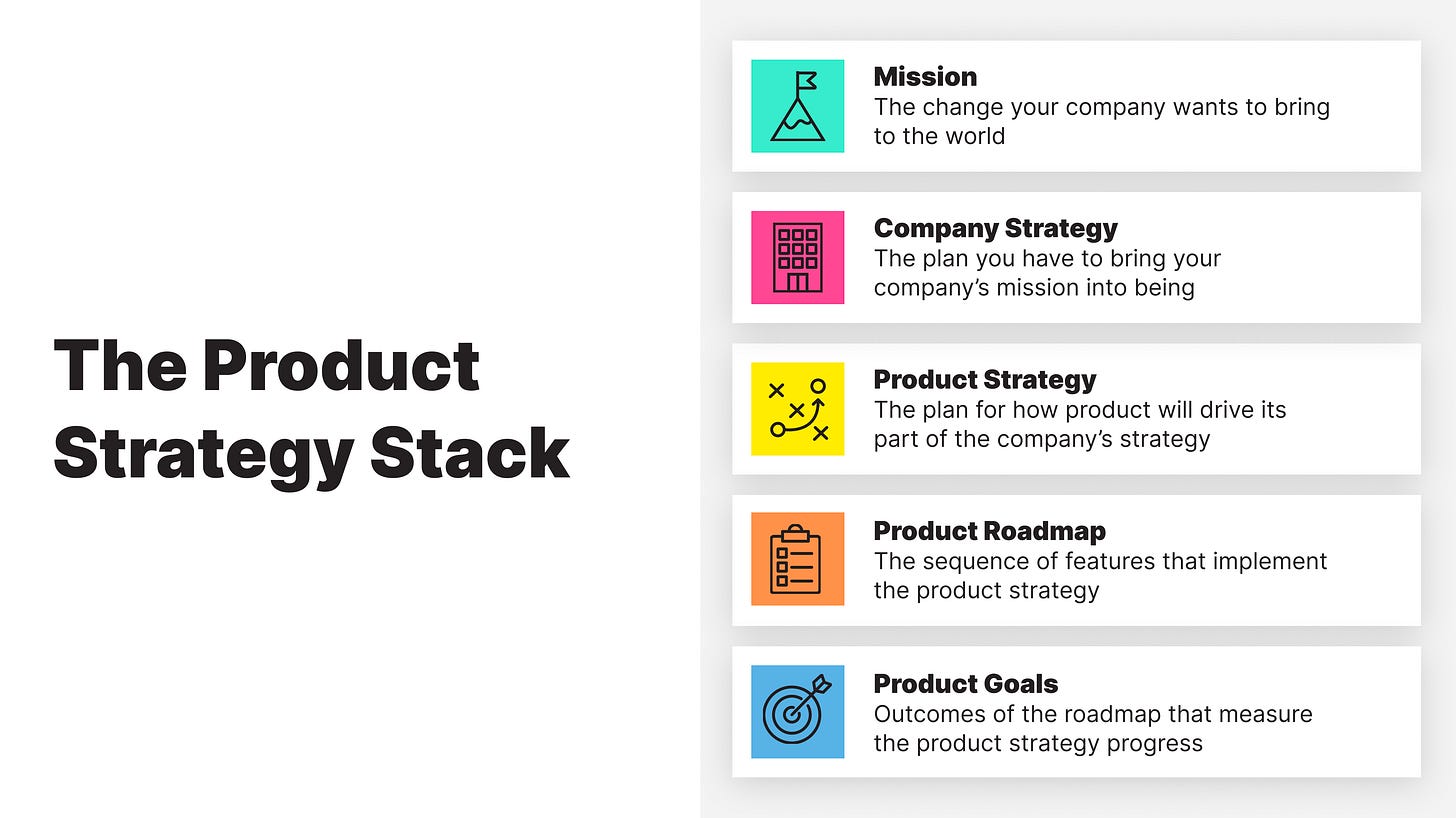

To combat this disconnect, he introduces this idea of the “Product Strategy Stack” — AKA the company mission, company strategy, product strategy, product roadmap, and product goals.

A big takeaway from his career as a leader and advisor is “the importance of creating a product strategy that fits into the broader ambitions of a company, prioritizes long-term objectives rather than short-term goals, and is well-defined relative to the strategy.”

In other words, this framework helps makes sure there’s the right level of focus and context across a team.

But before digging into the key pillars of the Product Strategy Stack — how do you know if you even have a strategy problem?

Ravi flags a few common failure modes he sees from teams across the ecosystem (company/market agnostic)…I’ll summarize:

Goals ≠ Strategy

Many teams underemphasize strategy and overemphasize goals. But, strategy is not the same as a goal. Saying “our strategy is to get big on X” does nothing to actually make that happen.

Goals should come from the roadmap, not the other way around, and he argues that being too goal-orientated at the cost of strategy can be detrimental. As he says: “I often see teams get into a mode where they’re just doing anything and everything to move the goal, without actually realizing they’re headed in the wrong direction from a strategic standpoint to create long-term value.”

Product Strategy Should Not Exclusively Live in the Product Org

On the quest for product traction, Ravi has seen many PMs get stuck in tunnel vision, noting that “as companies have gotten more product-oriented and product-centric, product strategy accounts for a really big percentage of the overall company strategy — but it’s not the whole thing.”

Crucially, product strategy should fit into the broader ambitions of the company and plug into what’s happening on the marketing, sales, ops, and product/engineering sides. Creating a product strategy without a thorough understanding of the company strategy, as he says, “is like going to the grocery store with a list of ingredients to buy, but without a plan for the recipes you want to cook.”

Good Strategy Hygiene Makes Prioritization Easier, Not Harder

Startups with a product strategy problem lack clarity and prioritize goals over strategy, which can lead to a poor user experience. Why? Because with no real context to make a decision, prioritization becomes much more tricky. He crystallizes this perfectly: “Without a solid product strategy you end up with products that have a Vegas effect — there are so many flashing lights vying for the user’s attention because each team has its own isolated goals.

So, those are some signals that suggest if there’s a strategy problem. To pulse check, you can ask questions like:

How are teams making decisions?

How are those decisions manifesting in the product?

Are most decisions aligned towards the short-term? Or are they laddered up to a long-term objective?

And if you find there is one, the framework Ravi co-developed with Zainab Ghadiyali can help course correct. It’s since become standard theory at Reforge, and I think it’s an excellent way to frame the flight path (big picture) all the way down to the tactical elements like how much fuel is needed (execution). 🛫

Here is is…

“The Product Strategy Stack”: 5 Steps to Startup Success

The idea is to start at the top, the 30,000ft view, and then work your way down to the details. This is how to achieve long-term success, because it takes the emphasis away from the goals (like improve retention by 10%) and shifts it more to what the team is actually trying to achieve.

Ok, sounds good!

But what’s some tactical advice on how to craft your own strategy doc?

First, Ravi suggests everyone runs this exercise:

It's helpful to take a fresh look at every piece of the Product Strategy Stack, because oftentimes even if a company feels like they have a really good strategy, there may be gaps that the team is hitting on.

I’ve seen some of the best startup product strategy exercises go from a completely blank slate to a really clear set of goals in 2-3 weeks if you stay intensely focused on the exercise.

It’s work, but investing some effort in circling back to first principles can have a big return-on-time.

So, to do that:

First, get executive buy-in on investing the necessary time to flesh out each pillar of the stack. Then start from scratch to find gaps in the current product strategy, working with at least one leader from each team that’s affected.

“You want the founder or the CEO to lead the way here, and continuously reiterate that this exercise of defining and documenting the product strategy is the most important thing the company can do in the next couple of weeks — not hitting a specific goal or shipping some project.”

Then, to capture the insights from the group, use a slide deck with plenty of wireframes to illustrate how to take the abstract, strategic ideas into interfaces for the user. Ravi suggests these tips in structuring your deck:

The first slide should always have a clear company mission. Start at 30,000ft and work your way down to the details.

When working on company strategy, make sure to bring in the customer by having a slide on the target user and the key use cases. This makes sure that strategy is tied back to the customer's needs. "Oftentimes when crafting a strategy, the company focuses too much on itself and what it wants to achieve, and not enough on what’s best for the user.”

Use wireframes to make structural decisions in a visual way. “I recommend having 10-20 wireframes because really good product strategy isn’t broad and vague. It’s big, conceptual and ambitious — but also specific and concrete. It needs to be something that the team can execute.”

List out the next 100 days with the initial sequence for how to build towards the north star for what the product looks like

Show how you’ll track your progress. The final piece is the goals for the next quarter. How are you going to measure progress against your product strategy? These goals don’t necessarily need to be metrics. They can be things like gaining a deeper understanding of a market, building out a particular feature or launching a feature.

Get specific about what you’re not going to do. This process will force you to make concrete choices — so document them, including what you said no to. These non-goals are important, because “as product leaders, every choice we make is a choice that we save our users from making. If we're not clear about what we want our product to do, we shift that lack of clarity to the user.”

To go deeper, here’s some further study on this:

Now, one strategy worth considering as a startup is how to become a camel.

Um, what?

Why startups should become ‘Camels’ – not Unicorns

Perhaps you’ve heard terms like camel and zebra being thrown around to describe startups in the last 2-ish years. Ever since the term “unicorn” was coined in 2013 for billion dollar companies, it seems like we’ve become obsessed with giving startups an animal counter part…like the mystical dragon.

Or, the very real rhino, camel, zebra, and even the nuclear-proof cockroach.

And there’s a big argument, especially given the economic climate, that it’s much cooler to be a camel than a unicorn right now.

Now, there’s a lot of stuff on the internet about who’s who in the startup zoo — but today let’s just answer the simple question — why not unicorns, and why camels?

That might seem abstract and pointless, but there’s value in thinking about what it means to prioritize sustainability over crazy fast growth.

Why not Unicorns? 🦄

The era of the unicorn is over.

That doesn’t meant there won’t be more billion dollar startups, rather that founders should stop obsessing over reaching valuations like that as fast as possible.

Why? Because it’s the desire to achieve rapid growth and high valuations, without considering the long-term sustainability of their business models, that put’s people in a position to fail.

Sure, a fire will rage on with no wood if you keep throwing gas on it — but gas is pricy. And if you’re just running in loops to round up more cash to keep the fuel coming, you’re going to be spending less time building a good base and adding solid logs to your fire pit.

That’s where the camel-like mindset comes in. 🕶️

Why be a camel? 🐫

Camels can go alooong time without new sources of energy. [Fun fact for the day: Over 2 weeks without water, and several months without food]. They also can survive through rough environments.

AKA — they’re the type of company that’s durable, adaptable, and able to weather economic downturns and market fluctuations.

As the Harvard Business Review describes:

Camels have no interest in “blitzscaling” — rapidly building-up the enterprise and prioritizing speed over efficiency in pursuit of massive scale. They are as ambitious to grow as any Silicon Valley enterprise, yet they take a more balanced growth path. This balanced approach has three key elements.

1. Right-pricing from the start. For one, entrepreneurs in developing markets don’t offer free or subsidized products to perpetuate customer growth, resulting in a high “burn rate.” Instead, they charge their customers for the value of their product offerings from the get-go. Camels understand that price shouldn’t be considered a barrier to growth. Instead it is a feature of the product that reflects its market position and its quality.

2. Cost management through the life cycle. At the same time, camels manage costs through the life cycle of their companies to align with a longer-term growth curve. Matt Glotzbach, CEO of Quizlet, an online education and study aid company, understands this strategy in terms of his cost of acquisition and his key expense: people. “You want to have a business that can survive the ups and the downs,” he explains. “Resiliency for me has two factors: one is the unit economics of the business for user acquisition, and the second is how far do you invest in headcount ahead of the revenue curve to drive that growth? This is where we make calculated decisions and have expectations for the investments where, if we’re right, we grow significantly, and if we’re wrong we won’t suffer significantly.”

3. Changing the trajectory. Managing burn throughout the life cycle of a company prepares startups to weather tough conditions over a sustained period. The typical Silicon Valley startup has a cash trajectory with a deep “valley of death” — the graph line reflecting steep losses before profitability is achieved. The line for Frontier startups looks different. Of course camels don’t avoid growth or venture capital funding, but their scaling trajectory and associated burn rates will be less extreme. In some cases, as with Grubhub, they’ll grow in controlled spurts, choosing only to put their foot on the gas and invest (often by raising venture capital) when required by the opportunity at hand. After such a spurt, sustainability (and often profitability) is within reach again if necessary. The difference here is that camels maintain the option to adapt their growth trajectory and return to a sustainable business.

— Startups, It’s Time to Think Like Camels — Not Unicorns, via HBR

With that in mind, here’s a cheatsheet with some key characteristics of startups like this. You can use it to think about how to be more like that cool-camel.

Resilient. They are preparing for the future through thoughtful, strategic growth.

Cautious. They maintain reserves to help get through tough times and replenish during the good. Their value lies in being financially conservative, hiring the right team, and focusing on building the technology that will revolutionize their industries.

Committed. They are dedicated to business-building fundamentals and stress positive unit economics early on, and every day, to ensure impact on long-term success.

Customer focused. The products they deliver and business models are all driven by customers needs.

Now, speaking on animals…

The Elephant in the room: The myth of exponential hyper-growth

Fast-growing startups are frequently described as “exponential,” especially when the product is “viral.” But “exponential” is an incorrect characterization, even for hyper-growth, “viral” companies like Facebook and Slack.

If your model is incorrect, you don’t understand growth, which means you can’t control it, nor predict it.

— Jason Cohen

In his [long and mathematical] essay, Jason suggests an alternate model for how fast-growing companies actually grow. I really like his thesis, so I’m going to do my best to synthesize it down for you today.

Because, in his own words: …understanding the model is useful not only for predicting growth, but because understanding the foundational drivers of growth allows us to take smarter actions to create growth in our own companies.

First, he dispels the notion of “exponential” by looking at some popular companies who grew rapidly, and who often get dubbed as examples of this growth model.

Let’s take a look.

Not exponential

It’s been a minute since high-school math…

Exponential growth = growing by a multiple. For example: In year 1 you grow by 10, in year 2 by 100, in year 3 by 1000.

Quadratic growth = growing by adding a constant. For example: Growing in year 1 by 10, then in year 2 by 20, in year 3 by 30.

In both, growth is clearly still accelerating, just at wildly different rates. To drive the point home:

Facebook is the definition of hyper-growth—getting to $50B in revenue faster than any company in history. The product is “viral”—friends bring other friends—which theoretically leads to “exponential growth.” But Facebook didn’t grow exponentially in the number of monthly active users:

Essentially linear for nearly twenty years, only exponential in the first four years.

Slack was the fastest-growing enterprise software company ever, going from $0 to $10M ARR in their first 10 months, and 0 to 10,000,000 active users in just five years. It’s also a “viral” product—organizations invite their members, who then create their own Slack-groups and invite others. So surely Slack has exponential growth?

Slack’s own data shows initial quadratic growth, followed by years of linear growth.

— Jason Cohen

So, given there’s no proof of an exponential growth model in startups — even looking at real-world data from the fastest growing companies (he also investigated HubSpot and Dropbox) — Jason points out that in fact… hyper-growth is quadratic.

But why do products grow quadratically?

It’s not enough to just say that growth in real-life is quadratic. We have to be able to know why this model makes sense, as this will give us a better understanding of the growth drivers in our own companies.

Luckily, Jason gives us a first-principles explanation so we have that insight, using the life-cycle of a marketing campaign as an example.

In my experience, marketing campaigns follow this pattern:

At the foot of the curve, we’ve launched a new campaign, but it’s ineffective; we haven’t figured out the best design and messaging and calls-to-action for this new medium and audience. Sometimes we never figure it out, and abandon the effort.

But in the case that we unlock the secret of efficacy, the campaign rapidly reaches a natural level of contribution; in this example, a number of “sales per week.” The specific level depends on many things: ad inventory, our budget, audience-receptivity, and the consonance between the audience and our target market.

Next we enter the optimization phase. We A/B Test our way to incrementally better results. Also we enjoy the result of multiple exposures—most people need to see the ad more than once before they act.

Finally we enter a phase of decline. There are various causes, all instructive:

The audience saturates. Everyone in the channel has seen the ad more times than is required to act; it’s now falling on deaf ears. Even if the audience is growing, the number of new people is small compared to the number of people that were new-to-us when we began the campaign

The channel declines. A media site that was popular loses readers through over-monetization. An event that was well-attended loses favor. A newsletter that was frequent and insightful becomes less frequent or other writers take over. A podcast moves to a closed platform and loses many listeners.

The auction becomes uneconomical. For auction-based systems like Google and Facebook advertisements, or other zero-sum programs like affiliates or limited-inventory spots on newsletters or podcasts, the winner is the one who will pay the most. What is cost-effective for one bidder will be laughably overpriced for another, due to better conversion rates, higher revenue per customer, higher profitability per customer, or due to categorization as a “loss leader” or other way of ascribing value beyond immediate pay-back.

He calls this…

Whether it’s a marketing campaign or a new product release, growth initially accelerates as early issues are solved, then grows roughly linearly as things are optimized, and then starts dipping overtime. That slowdown/decay is natural as things scale.

But, we don’t do single campaigns or releases, do we…we add new ones. Some end up being bigger than others, some can be better optimized, or decline sooner, and some decay more steeply than others.

So, companies that want to continue growing quickly after their first product reaches scale, must launch new products into new markets.

This leads to a variety of Elephant Curves across time —which, if plotted together — look very quadratic.

Okay, so what? What’s the advice for product managers?

The consequence of knowing that the growth we encounter at work is quadratic is important, as we’re all trying to understand (and likely change) growth drivers. So, “getting the right language, and the right model, will lead to correct analysis, and right action.”

And to leave you with something more actionable here:

It’s great to add a feature to an existing product, but significant additional growth comes from increasing carrying capacity or creating a new avenue of growth. Early on you should focus on winning market share in one space, creating the first Elephant Curve, but after the product matures, something more drastic is required: Wholly new products, or updates significant enough to address new markets.

It’s well-known that companies need to add additional products to continue fast growth after achieving scale. However the second product is highly unlikely to achieve same market share and monetary scale as the first, so there needs to be multiple, not just one. This requires serious investment, parallel efforts, and the chutzpah to kill off the ideas that aren’t working.

Because word-of-mouth-driven growth is so much more effective than marketing-driven growth (both in cost-per-customer and in that unlike direct advertising it grows automatically as the company grows), it is worth a great deal of time trying to figure out how to build that into the product, rather than relying only on the marketing team.

To go deeper on this, and get into some of Jason’s advice for marketers, you can here.

And while we’re busy talking about growth curves and how to keep that upwards trend…👇

What causes growth inflections?

As always, Lenny Rachitsky's research is above and beyond top-notch — always bringing us the insider insight into different companies.

And a recent post of his, “Growth Inflections”, dovetails really nicely on this idea of multiple Elephant Curves.

Here’s a peak…

Q: My product is growing, but slowly. I’m wondering if growth will ever take off. What have you found most often precedes an inflection in growth?

I love this question. Though I’ve written about how to kickstart a product’s growth, ways to boost growth, and what it feels like once you’ve found product-market fit, I’ve never looked into what precedes sudden inflections in growth.

To find an answer, I spent the past couple of weeks researching inflection points for two dozen of today’s most successful products, and I found a few surprises:

The majority of growth inflections sprang from a product improvement

A surprising number of growth inflections came from an unexpected external event, without the product changing at all

Many of the most durable inflections came from the company leaning into their primary growth engine (e.g. SEO, virality)

Below, I’ll share stories of growth inflections from Figma, DoorDash, Tinder, YouTube, Snap, Airbnb, and many others. Here’s a quick overview:

It’s important to note that long-term sustainable growth is never as simple as just one thing. Although a single moment can (and often does) ignite growth, to build a durable business you’ll eventually need to get all three pieces right:

Ongoing product improvements, to build something people want/need

Ongoing events that get the word out

A well-oiled growth engine

But it often starts with a single moment.

In the rest of his post, he explores the stories behind the companies shown above. It’s an excellent read. 👇

⛏️ Source + dig deeper: Growth inflections, by Lenny Rachitsky

And to wrap us up today and send us into the weekend…

Choosing the right game to play at a startup

This needs no introduction from me…I’ll let Dan Hockenmaier walk you through it.

Short thread on something I wish I had understood much better 10 years ago:

If you are ambitious, there are basically two games you can play at a startup.

Many people early in their careers (especially those from big tech, consulting, finance) play the wrong game, and lose both.

Game 1: Optimize for company outcome. Spend all of your time finding and fixing the highest leverage problems you can.

Game 2: Optimize for career outcome. Seek external signals like title, scope, and team size. Make sure you're "learning the right things"

The more your personal outcome and the company outcome are synonymous, the more obvious it is that Game 1 is the right choice.

Founders and people at startups with <10 people almost always play Game 1.

At the largest companies, it's more natural (and probably actually in your best interest) to play Game 2. This is close to the definition of why it is so awful to work at very large companies.

But at most startups, even those with hundreds or thousands of people, it's almost always the right choice to play Game 1. Doing so will result in a better outcome for the company, but also a better outcome your career, for two reasons:

1. Startups are an iterated game. Earning a reputation for playing Game 1 opens doors.2. It's actually very hard to know what is good for your career. Being pulled by the intersection of what the company needs and what you're good at works better than any "20 year career plan".

As a result, the right move is to focus on putting yourself in the best companies with the best teams you can, and then playing Game 1

— Dan Hockenmaier, via Twitter

And that’s a wrap.

Have a wonderful weekend, and I’ll see you on Wednesday morning for our next deep dive.

Until then.

— Jaryd ✌️