How Figma Grows: Design Beyond Designers

From $20B to the Nth. An interview with Figma's CTO on what's next.

👋 Welcome to How They Grow, my newsletter’s main series. Bringing you in-depth analyses on the growth of world-class companies, including their early strategies, current tactics, and actionable product-building lessons we can learn from them.

Hi everyone 👋

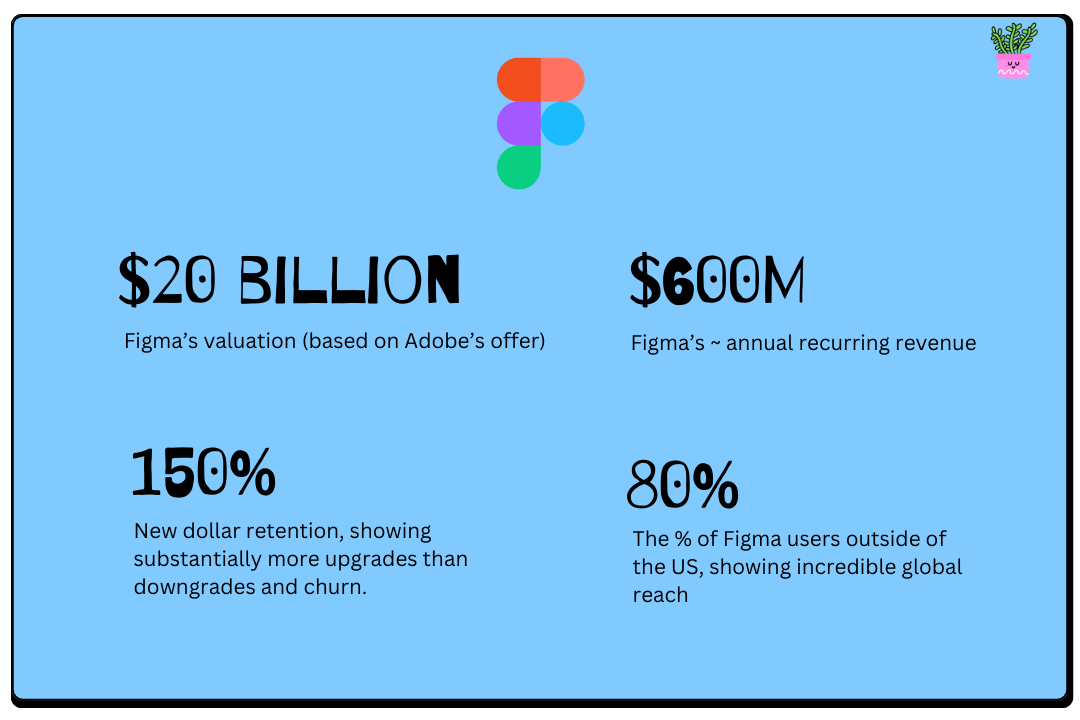

This is not our usual deep dive. It’s not the origin story of Figma. And it’s not an analysis into what got the #1 platform for design a $20B offer from Adobe.

I had plans to do that, but after Aakash Gupta did a stellar case study on their product and growth drivers, I didn’t think I had much to add to the conversation on that front.

So, today’s post is something different. It’s a look into what’s next for Figma. And not just from the lens of “What next?” given the Adobe deal falling through, but from a larger arc of “What got you here, won’t get you there.”

If you want the 0 to 1, I’d highly suggest reading Aakash’s post. I did a lot of research, and it’s the deepest by far. But for the 1 → Nth, you’re in the right place to get the goods.

Many companies are now at this inflection point. They have found success with their core product and are trying to push themselves to the next level of value to customers and scale. It’s very clear a core insight of Figma is that design is larger than just designers.

To help with this piece, I was insanely lucky enough to snag an interview with Figma’s CTO, Kris Rasmussen.

We chatted about what that push past the inflection point looks like for Figma, while at the same time, getting into as many tactical elements as possible.

Let’s get to it.

Here’s what to expect in today’s analysis:

A quick recap of 0 to 1

Figma’s scorecard

Breaking away in a crowded market

Leveraging inflection points

Indexing intuition; ignoring naysayers

Incredible customer proximity; product-empowered engineering

Growth: For Design, Not Just Designers

What the Adobe deal changed

The big picture, sequential loops, and welcome to the WIP

M&A, and operationalizing integrations

Balancing resources across a portfolio of bets

How AI will lower the floor and raise the ceiling of design

Bonus: What makes a great product builder at Figma

A quick 0 to 1 recap

For anyone who isn’t familiar with the backstory of Figma, here’s a very quick primer for context. Again, there are much deeper posts on this part of the story if interested.

But, Kris and I did chat a bit about the earlier days just to get the conversation rolling and calm my nerves 😬, and here are a few things that stood out to me that are tactical, and not that covered elsewhere.

11 years in 30 seconds

To set the scene, it’s 2013.

Besides me flunking math in my first year at University and Miley’s Wrecking Ball being my #1 song, unbeknown to me and everyone else, Dylan Field and Evan Wallace had an idea that would forever change not just the design scene, but the entire product-building landscape:

What if we brought design software to the browser, and at the same time, we made design multiplayer?

Doesn’t sound so crazy now, but back then, as Kris reminded me in our chat, it was a colossal technical challenge. And tech difficulties aside, the next big obstacle was actually getting designers to change their entire workflow and switch tools.

The noteworthy players back then were Adobe, as well as innovative startups like Sketch, Framer, and Invision. So, there was no shortage of competition.

That’s why Dylan and Evan rallied a team and built in stealth for 3 full years. Until September 27, 2016, when…

And they really did come in like that…stylishly wrecking everyones market share.

Today, if you need to design anything, it’s not even a question (IMO) where you should do it. Figma is the place.

Here’s their impressive scorecard.

That’s a significant snatch up of market share, especially when noting that those other tools were very good. I personally used Sketch, Framer, and Invision all the time at my startup, and I loved them.

So, of course I asked Kris about what he thought contributed to this breakout success. 👇

Breaking away in a crowded market

The first thing he said, despite popular opinion, is that it wasn’t so rapid a win.

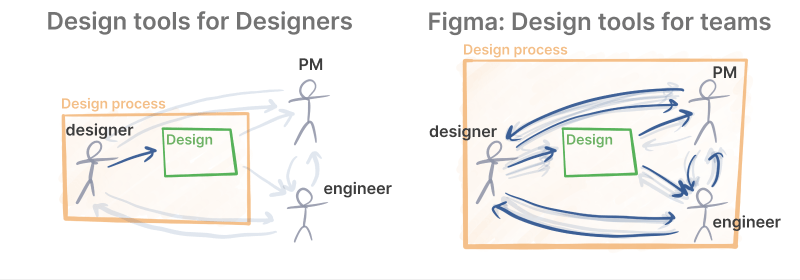

Rather, there was a ton of patience and working behind the scenes as Figma set out to create a new category of design software. Let’s call it browser-based design for simplicity, but in reality, the browser was just the vessel to get to Figma’s true 10X value add and actual category: a platform for teams to design, vs an app for designers alone.

Kevin Kwok illustrates this well:

And Kris’ emphasis on patience is an important lesson. A lot of founders are scared to do things that take a long time. They want rapid growth. But for the really big ideas—the category defining products that go against all conventions—it’s important to do things that might take years, not months.

Not everything can be done quickly, and the interesting challenges do take time.

Dylan and Evan had a strong vision for what the future of designed looked like. And they spent a long time working away at that vision, rallying people around it, and motivating stakeholders all while persevering through a lot of learning and a lot of hard technical challenges.

That takes real grit to work in stealth for 36 months before even getting to the point where they could even open the product up to the public and start to get real feedback.

Let’s touch on the technical challenge…

Leveraging inflection points

When Dylan and Evan were ideating Figma, there were two big things worth noting:

The state of design tools was entirely desktop based.

It was becoming obvious what the benefits of browser-based tools were, and more people were leaning into them (Google Docs, etc)

This left a big question: Was it possible to bring a collaborative, browser-based tool for design, to the browser. Because historically, browsers weren't good at custom graphics-oriented type things. And that’s table-stakes for a design tool.

So, Figma took two huge bets:

That designers would want multiplayer design tooling in a browser (besides them not explicitly asking for it)

That the technology behind the browser would improve, thus making Figma feasible for high fidelity design.

Both were bets based on seismic shifts they saw happening in the market. The first, a behavioral shift towards changing consumer needs. The second, a technology (and timing) bet.

To Dylan and Evan’s credit, they recognized early on that there were already some advancements in browser tech, indicating that their vision would become possible.

And importantly, besides the criticism, they continued to believe that these challenges could be overcome. Because it's not like signal was fast from day one. When I joined, there were a lot of performance problems. And we could've just said it doesn't make sense to build our own render. We could have just given up and pivoted to desktop software, and we honestly had lots of people on the team telling us that all the time.

— Kris

This gave Figma a very compelling Why Now (WebGL in browsers), which is a classic stripe that most massive and enduring companies have. Lenny has a great post on the importance of Why Now, but in short, startups have a higher chance of success when their insight is built on some big and accelerating change happening in the world.

A change that is in the early innings of playing out, because a) it means the opportunity later on is much bigger than it is today, and b) anyone working against it now has early mover advantages.

So, how can you spot a wave to catch?

Well, first know that there are two main types of why nows.

Demand why-nows (shifts in what people want and need). Examples:

Changes in societal norms, preferences, or behaviors, including new uses of technology

Shifts in population demographics

Shifts in your customer’s industry dynamics (especially ones that reduce profitability of the status quo)

Changes in your customer’s competitive landscape (including recent, widespread disappointment with competitor products)

Regulatory changes that spur demand for your offering

Supply why-nows (some recent advancement that makes your solution more possible, affordable, or profitable). Examples:

Newly available technologies or data

Changes in the economics of supply, production or distribution

Regulatory changes that make it possible to deliver your offering

Changes in your competitive landscape

As said, Figma hitched onto both types, which was great because supply why-nows are most powerful when combined with demand why-nows.

And to find them, speak to your customers, get insights from the sales team, stay up to date on advancements in tech by following a few of the right sources, look at which sectors are getting funding, and keep a pulse on your competitors.

Speaking of demand-why nows…

Indexing intuition; ignoring naysayers

Again, Figma took a bet that what designers would want and need to design better was going to have to be delivered through a browser.

Sticking to their guns and pushing through towards that vision must have been extra challenging since Figma had a lot of criticism when it launched, with designers being very vocal that this was not were they wanted design to go.

Part of that criticism probably came from the fact that there was a disconnect between what the market saw as currently possible, vs what the Figma team knew was becoming increasingly possible.

Which brings us to an important point: you most likely know the most.

You’re closer to things like important tech advancements than your customers. You have better proximity to the market, and you’ve probably got much more data and access than the layman…be that the press, or a customer.

That definitely does not mean ignore your customers. As we’ll see, Figma values a very tight proximity to their community. But it does mean you have to sharpen your sense about what to ignore, even if it seems like existential feedback (e.g I hate your vision).

Just remember, people said they hated Facebook’s News Feed when it launched (it went on to become the foundation of their success), and the first iPhone had plenty of high-profile doubters.

There will always be criticism. And I think that the more vocal the criticism is from a group of people, perhaps there’s some correlation there with the level of success a product will have. Don’t quote me on that, but I’d rather have a bunch of people saying my product is terrible, that nobody saying anything at all.

Just a hot take.

Incredible customer proximity; product-empowered engineering

One tactical thing worth noting about Figma’s culture in the early days, and to some degree, still through to today:

They make sure everyone at Figma uses Figma. Dogfooding their own product is a key principle.

They had/have everyone, including devs, spend time with customer support.

One of the things we value is people who can simultaneously keep the big picture in their head, but also aren't opposed to diving deep into the details to ensure their vision is playing out in reality.

I think talking to customers is a core part of that. And even if engineers aren't necessarily always talking to customers as much as they did in the early days, they're still like checking to see if the products they're releasing are being used the way they expected. They're looking at metrics, and then they're finding specific users who might give more insight into why the metrics are the way they are.

So, I think that it's very much still a part of our culture. But because we have all these other functions to support us, we're a little bit more thoughtful and strategic around when we dive in and how we dive in.

— Kris

Product-empowered engineering is a key lever to building and shipping fast. When we looked at beehiiv who build with crazy velocity, this is one of their key speed drivers. You want engineers looped into customer conversations and strategic planning, because it means they have deep context to make decisions quickly while they work. This does not make the PM redundant, but it does make the entire process a lot smoother and lift the quality bar of the product.

And when you use Figma, it’s very easy to see how high that bar really is.

Now let’s get into what’s next for Figma…

Growth: For Design, Not Just Designers

What the Adobe deal changed

Let’s just start by addressing what everyone’s wondering…what now given Adobe isn’t acquiring Figma anymore?

In short, Figma has cleared the decks. They’re no longer distracted by an acquisition. They don't have to worry about it anymore. And as Kris said, their path is very clear; they have open road to move even faster on their vision and roadmap.

Now we can just double down on what we were already doing, and we can also focus more on all the new opportunities, like AI and ML, that this shifting technical landscape presents for turning ideas into reality. There's a tremendous amount of new opportunities in these areas that we're excited about.

— Kris

I think a lot of folks who use Figma are happy to hear they will remain just being Figma.

Getting acquired can be exciting, and of course, incredibly lucrative. But often from a customers stand point, the best outcome is by and large for the team to just continue focusing on the product they’ve come to love.

When M&A happens, integrations usually follow in some form. These almost always mean there’s some tradeoffs to make the integration happen vs building new features.

At Figma, any time that would have been spent on integrations and assimilating to a new culture can now be spent on expanding the core and building best-in-class software across the holistic product-building and design stack. All while keeping their startup culture of urgency and making things as fast as they can.

Long term (3 to 5 years), that means Figma will most likely IPO. To be clear, Kris did not say that. But as a private venture-backed company (with 9 financing rounds), that’s really now the inevitability. The deal with Adobe was terminated because of too many regulatory roadblocks in the UK and EU. So, unless for some reason it is picked up again (which I doubt), there isn’t really anyone else who can buy/would buy Figma and not run into the same hurdles.

So, the exit path looks very much like going public.

And with the team’s focus being fully on growing Figma, let’s look at how they’re thinking about the next chapter, potentially making Figma a $50B+ company geared for an IPO.

The big picture, sequential loops, and the WIP

A common thread I kept hearing in my chat with Kris was how Figma was thinking about catalyzing compounding productivity in design.

And a critical part of this for Figma is expanding the platform beyond the core “design” function. Their insight driving this strategy is that design goes beyond designers. It’s equally all of the conversations around what to build. The feedback cycles, the prototypes with users, and the handoff specs.

Therefore, there are other key stakeholders, adjacent problems, and big opportunities that Figma has core advantages in addressing. And the more that Figma can stack solutions for them into one tightly integrated platform, the more Figma will be an essential part of every type of teams product delivery process.

To illustrate how Figma has rolled out towards this vision:

GTM wedge: Core multiplayer design tool (Figma) → win designers over

1st Expansion Multiplayer whiteboard/brainstorm tool (FigJam) → win PMs over

Latest Expansion: Translate design to code (Dev Mode) → win engineers over

Once Figma had designers thanks to their best-in-class design tools, that was their break into the company’s product-building function. From here, designers became their internal champions for Figma. So, when they began building products for other folks on the team to help the holistic design process, they had massive distribution advantages.

Now, this is what Figma looks like when you work with your team: a community playground to build beautiful products.

So, peaking into Figma’s future, the playbook is clear:

Keep taking design to new levels (both by raising the ceiling, and lowering the floor)

Keep picking problems to solve that make the idea to product-delivery smoother for a team (by finding ways for non-designers to be engaged in the design process)

That last point is really the North Star of Figma’s roadmap: vertically integrate the value chain of what it takes to think about, get buy-in for, design, code, ship, and measure software. That could mean build, buy, or partner.

And the more Figma inserts itself along this value chain, each step will make Figma an increasingly valuable part of a company’s stack. In turn, very likely making some other SaaS licenses a company has redundant, increasing their net dollar retention, and selling more seats to a company.

This is how Figma will grow—through sequential loops.

Sequential loops

Companies, as Kevin Kwok put it, are just “a sequencing of loops”. And while it’s possible to GTM and cruise with an initial core loop that works well, it’s usually not enough.

What got you here won’t get you there. AKA, you generally can't accomplish what you want/need to in the long-term with a single loop.

This is because every single product has a natural lifecycle that ends with a flatter maturity line. Growth rates always tapper off.

This is where the idea of S-curves comes in. To keep growing—just like a fire needs fresh logs—a company often needs to keep finding the next loop that piggy-backs on existing strengths.

Each S-curve, or new product launch, hopefully brings a new growth inflection.

Simply, the more problems you solve in one place, the bigger your surface area of value is, and the more of a compound startup you’ll be.

A compound startup is just company that instead of just doing one very narrow thing well, tries to build a whole set of different point solution systems in one coherent product and tackles them all at once to solve a much larger problem for someone.

Conventional wisdom bucks that going niche and deep on one problem is a winning strategy (at least, to start).

So, why would you do this?

Simply, because the companies that tend to be bigger and more ambitious are solving the whole problem as opposed to just building a tool.

As Parker Conrad, founder of Zenefits and Rippling, describes:

When you think about the problems your clients have, they often span a lot of different business systems or point solutions.

In fact, I think some of the biggest problems, and therefore the problems that potentially could give rise to the most valuable companies tend to be things that span a lot of different point solution products within a business. And therefore, only building one point solution product can't really address them.

Once upon a time, a small company could dominate a super niche space. But now there are actually a lot of different companies operating in all of these different narrow-point solution verticals. So there is actually now a lot more opportunity if you can go bigger and combine a bunch of these different point solutions into one product.

In other words…think in ecosystems. The more you do, the deeper your moat will be.

Just take these examples of world-class ecosystem plays:

Shopify: All things e-commerce

Stripe: All things payment infrastructure

Atlassian: All things DevOps

Alchemy: All things Web3 development

HubSpot: All things CRM

So, to differentiate themselves from a commodity market of design apps and stay ahead of the competition, Figma is gunning to be the ultimate ecosystem for all things design.

And by building for everyone in the design process and not just designers, they drive growth thanks to cross-side network effects.

Unlike direct network effects, where more people get more more value as more people like them join (think social media or messaging apps), cross-side network effects involve multiple groups that grow in size and value as the other group does, too. This is just classic two-sided marketplace dynamics—more buyers mean more sellers, driving more buyers, etc.

As more designers use Figma, they pull in the non-designers they work with. Similarly, as these non-designers use Figma, they encourage the other designers they work with to use Figma. It’s a virtuous circle and a powerful compounding loop.

So how does Figma pick their next loop?

Simply, expansion stems from existing advantages.

In the context of thinking through how we continue to deliver more value to more audiences that could be benefiting from Figma’s tools, we think a lot about going from strength to strength.

We look at how people are already using our tools, and we look in places where people are showing high intent or trying to do things that maybe we're not the best at yet. From there, we think about how to make the experience better for them, and if more broadly, there is a larger opportunity for us.

— Kris

FigJam is good example. During the pandemic, they saw a lot of people using Figma to brainstorm with diagrams and whiteboards. They also knew a Figma design seat wasn't the best way to monetize the rest of the company, so, they built a specialized version of Figma to address this demand.

And this leads us to a super important point…

The WIP, and the balance of being strategically proactive and reactive

Figma has a long term vision, which leads to long term strategy.

That is all incredibly important, and everything you work on and prioritize should have a strong story for how it helps get you towards that 5 to 10 target state.

But we also live in a world where things are always in flux. New technology can become rapidly popular. Pandemic could strike. A competitor could make an unexpected move, or your customers may suddenly need something based on some market or world change.

Things happen. And as Yuhki Yamashita, Figma’s CPO, put it: We live in a WIP (work in progress) world.

In a great post, Yuhki gets into how the WIP drives Figma’s day-to-day product-building philosophy. But it also clearly impacts how they view strategy. Here’s what Kris said:

One of the things that I've really been impressed by with Dylan, and just the Figma culture in general, is this blend of having a vision for where things should go, but also being cognizant of where people are and what they need in the moment, and then trying to balance those two desires. It’s not just about being purely visionary, but also being reactive and adaptive. You need to know what people need right now.

Just to repeat: Now matters. Now can create sudden opportunities for you. And while now may not perfectly tie to your long term plan, being adaptive is key to customer-centricity.

It reminds me of this Paul Krugman quote:

“Economics is really about two stories. One is the story of the old economist and younger economist walking down the street, and the younger economist says, ‘Look, there’s a hundred-dollar bill,’ and the older one says, ‘Nonsense, if it was there somebody would have picked it up already.’ So sometimes you do find hundred-dollar bills lying on the street, but not often—generally people respond to opportunities.

To find and grab those $100 bills, make sure to strike the balance between big growth bets, and “what do people need today”. Of course, you don’t always have to build something yourself to lean into a short or long term opportunity.

M&A, and operationalizing integrations

When the Adobe deal was terminated, Adobe had to a pay a $1B separation fee. This gave Figma a nice cash injection, filling up their war chest.

Now, as Figma expands across the design value chain and enters new verticals, M&A becomes a very viable strategy. Either they can invest in building, or they can invest in buying.

For instance, they recently acquired Dynaboard, which plays well into their push into the design-to-code phase of the chain.

They’re betting big on developer tools, and here M&A accelerates their growth in this area by a) bringing in great talent to grow the team, and b) folding in new tech to add further functionality.

Give my recent post on Good Acquisition / Bad Acquisition, I was curious how Figma thinks about M&A.

The vast majority of our acquisitions have been for talent, and the reason for that is not because we're fully opposed to acquiring existing businesses or things that are really interesting, but because we don't want to be a portfolio of disconnected products. We want to build things that work really well together. And we have a very unique technical stack to integrate with. So, first and foremost, when we're looking at companies to acquire, we're assessing the talent. We're seeing if they're the kind of people who, independent of whatever they might have built in terms of the business, would be successful at Figma.

That's the primary motivation for all of our acquisition scanning activities.

And it’s not that we're against strategic acquisitions, we look for those opportunities too. But we have to approach those extremely thoughtfully in terms of whether or not it integrates with our existing product strategy, and also whether or not it makes sense in the context of our tech stack and overall goals of how our products need to work together.

— Kris

In other words, Figma will buy talent and technology to either:

Add a new sequential loop

Enhance an existing loop

Both will expand their ecosystem vertically, and when buying a company for this reason, it presents the potential to really drive a better experience for your customers and thus build real value (vs just a roll up strategy with a portfolio of disjointed products)

Customers enjoy the convenience of features talking to each other

Customers get better personalization thanks to their data being in one place

Customers enjoy favorable pricing

And of course, for the company there are a ton of reasons why this works:

You can cross-sell between customers

You retain your customers for longer in your ecosystem (they don’t need to use other tools)

You have control of product quality and can influence the supply/value chain

You unlock new revenue since you can charge for solving new types of problems

You create network effects, increase switching costs, and generally just build a moat for yourself

For this to work, you as the acquirer need to (1) understand your audience super well, (2) identify adjacent problems in their lives that a) you are not solving, and b) make sense for you to solve, and 3) pick potential acquisition targets that align with your strategy.

Some other examples here: Atlassian’s suite of acquisitions across the DevOps pipeline, Twilio building a communication platform, and Intuit’s aggressive expansion (45 deals!) across the financial sector.

Balancing resources across a portfolio of bets

It's always challenging for companies to go from 1 to n products.

One of those challenges is managing the shift in the allocation of resources between a company’s core business, and their future expansions.

Because even if it’s not about vertical integration, every company should have a diverse portfolio of bets on their roadmap. Some bets will be a small lift, others, like FigJam or Dev Mode, are bigger bets that need real teams behind them.

The question is always how do you staff them. There are always tradeoffs and opportunity costs, right?

To help with this problem, first, Figma emphasize the time spent in discovery and conviction building. They don’t jump to solutions, and through engineering and design crits (brainstorming rituals where no decisions are made), they ideate in the problem space until there is a enough confidence in the hypothesis and proposed solution.

This means prototypes and a lot of assumption testing.

From there, they start with a small team to get to building. You would never guess, but FigJam was built with just 1 PM, 1 developer, and 1 designer.

As the market validates their idea further, they ramp up the team.

It can be tempting to just fully staff a big and exciting initiative, and while there are certainly situations where you need to move fast on a big bet, and investing big early on is necessary, it’s usually best to think about allocating your resources based on a function of confidence and impact.

Another thing that Kris and I spoke about here is economies of scale. This is really how a single engineer could build FigJam in 6 months…it was built on the same engine. So was Dev Mode.

One thing we’ve found helpful as we’ve added our second and third products, is to figure out what the common challenges we’re facing are as we try to introduce these new products, and how we can further reduce the accidental complexity and hard decisions that come up over and over again.

Our basic goal is trying to make it so that when we add our fourth or fifth new direction, it's less about creating a new product, even if that's how it's ultimately perceived by the market, and it's more about adding new integrated functionality and features that just make that entire suite of products much more powerful and compelling.

— Kris

Essentially, Figma has built a unique tech stack for themselves, and this stack has become a shared engine with shared operating principles, systems, permissions, and data models that can power all new their new initiatives. This has 3 very clear benefits:

Engineers who have worked on one product area can easily transfer over to another product area

New product initiatives needs less infrastructure to get going, meaning 1 person can build an entirely new product

When working on one product area and making improvements, other product areas also improve, creating a self-reinforcing flywheel

How AI will lower the floor and raise the ceiling of design

So far, we’ve spoke about Figma’s future being continued expansion through more and more connected loops along the design value chain.

This is all towards their vision of turning imagination into reality.

Which while I was speaking with Kris, I kept thinking of Ben Thompson’s concept of The Idea Propagation Value Chain. Here’s an excerpt from his essay:

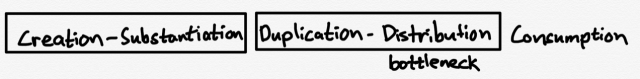

As much as newspapers may rue the Internet, their own business model — and my paper delivery job — were based on an invention that I believe is the only rival for the Internet’s ultimate impact: the printing press. Those two inventions, though, are only two pieces of the idea propagation value chain. That value chain has five parts:

The evolution of human communication has been about removing whatever bottleneck is in this value chain. Before humans could write, information could only be conveyed orally; that meant that the creation, vocalization, delivery, and consumption of an idea were all one-and-the-same. Writing, though, unbundled consumption, increasing the number of people who could consume an idea.

Now the new bottleneck was duplication: to reach more people whatever was written had to be painstakingly duplicated by hand, which dramatically limited what ideas were recorded and preserved. The printing press removed this bottleneck, dramatically increasing the number of ideas that could be economically distributed:

The new bottleneck was distribution, which is to say this was the new place to make money; thus the aforementioned profitability of newspapers. That bottleneck, though, was removed by the Internet, which made distribution free and available to anyone.

What remains is one final bundle: the creation and substantiation of an idea. To use myself as an example, I have plenty of ideas, and thanks to the Internet, the ability to distribute them around the globe; however, I still need to write them down, just as an artist needs to create an image, or a musician needs to write a song. What is becoming increasingly clear, though, is that this too is a bottleneck that is on the verge of being removed.

— The AI Unbundling, Stratechery

That last point is spot on, and around that Creation→Substantiation piece of the chain, there are tremendous opportunities that AI and Ml presents for turning ideas into reality quickly, and with little learning curve.

Essentially, AI will:

Give superpowers to professional designers (raising the limits of how good you can be at designing)

Give enough power to non-designers so they design (lowering the minimum skill required to even participate in design)

As Kris said:

And over the past decade, we've been simultaneously a) trying to make design more accessible to people who traditionally wouldn't consider themselves a designer, but have great ideas and want to visualize them. And b), making professional designers much more efficient by giving them more leverage and economies of scale.

AI accelerates all of that. I think it has the opportunity to raise the ceiling of what designers can do by virtue of shortening iteration cycles and making repetitive rote things a lot less tedious.

And here’s a snapshot of Noah Levin’ presentation from Config 2023 that visualizes it:

Raising the ceiling will make Figma more valuable for their existing customer base, since most professional designers already use Figma.

But, lowering the floor will help Figma move down market into some of Canva’s territory. There are plenty of non-customers out there that could start coming to Figma if AI makes getting their ideas into some wireframe or whatever much easier.

That would be an incredibly strong position to be in—having one product suitable and for servicing the entire spectrum, from amateurs to pros.

And the way Figma is philosophically thinking of using AI across their platform, is by shifting the thinking from atoms—the pixels and small details—to patterns.

For example, in the current Collaborate <> Iterate cycle, here’s what Figma is thinking:

Brainstorming with FigJam: Use AI to spin up generative concepts, clustering ideas, summarizing feedback

Designing with Figma: Use AI to get started faster, create variations, create design systems, complete user flows, convert designs to versions in new languages, or even on new device types.

Building with Dev Mode: Use AI to help with handoffs, generate code, and match components.

Essentially, here’s my read:

Figma will build new loops across the value chain

And they will use AI to:

Join the loops better, making transitions super smooth

Shorten the time spent in each loop

AKA, it’s a lubricant that will make the entire process way easier. Plus, Figma has tons of first-party data that gives them huge advantages here.

Finally, what makes a great product builder at Figma?

I asked Kris what he’s seen as the most common trait of successful PMs and operators at Figma, and he gave me two great answers that in fact are not just advice for the PMs reading.

First…

I think the best PMs help teams converge quickly on the right problems and solutions, without worrying about whether or not the problem or solution was originally their own idea. Sure it's great if they have the ability to do all of this on their own, but it's even better if they can make it an inclusive process.

— Kris

There’s definitely a correlation here with junior to senior folks. The less experienced you are as a PM, the more you want to prove that your fingerprints are all over things. Partly because that’s how you get promoted—showing that you led to impact.

But as you push up towards leadership, that matters so much less because you’re more measured on your ability to be a force multiplier.

What you start to care far more about is team and product progress, and recognition or attribution becomes a distant second.

The best way to lean into this skill is simply to listen much more than you speak. Ask questions of your team, and be a facilitator of conversation vs a public speaker. Even if you have the best product sense and design intuition, let others speak first and truly be curious to understand opinions that go against your own.

This, of course, applies to everything in life.

The second thing that Kris said the best PMs have in common, is their ability to reason about things at multiple levels of abstraction.

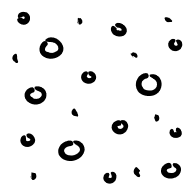

To give you an example of what that means, you can think of this image…

…at various levels of abstraction, such as:

• a collection of light and dark pixels, or

• a collection of carefully arranged dots, or

• a collection of letters, or

• a collection of words, or

• various parts of speech (a pronoun, a verb, an adverb, an article, a noun), or

• a subject and a predicate, or

• a sentence, or

• a thought.

In product, this means the best PMs can think simultaneously about the user experience, but also reason about features as a system. They know the technical constraints well enough, and consider how doing X may add complexity to the existing Y and Z. They also can reason through the implications of their work on the pricing and packaging model, even if that isn’t their product area.

Working through varying levels of abstraction is also how you build a ton of trust as a PM. When you know enough about the technical side, engineers trust you. When you reason through design choices, designers trust you. And when you reason through the business angle, leadership trust you.

And product management is largely a game of trust, since we influence by and large without authority. If you can’t influence, you can’t get anything done.

So, how can you develop your skill of moving across multiple areas of abstraction? Here are 4 tips:

Understand the Fundamentals: The best place to start is solidifying your understanding of the core concepts related to your product and industry. This includes both the technical aspects (how the product is built, the tech stack used) and the business aspects (market needs, business model, user personas). Having a strong foundational knowledge makes it way easier to navigate quickly between detailed and high-level perspectives.

Practice System Thinking: System thinking is a way of understanding how different parts of a system interact with each other within the whole. It’s particularly useful in identifying leverage points where a small change could have a big impact (like what growth models aim to do). Practice mapping out systems, identifying interdependencies, and considering outcomes of changes within those systems.

Practice Articulating Your Thought Process: Try to regularly explain your reasoning from both a high-level strategic perspective and a detailed perspective. The simplest step is just discussing your thoughts with your team and walking people through your decision. Just saying it aloud will force you to clarify your thoughts and make the connections between different levels of abstraction more concrete.

Develop Scenario Analysis Skills: Practice exploring how different decisions might play out across various layers of abstraction. This involves considering multiple future scenarios (best case, worst case, most likely, etc.) and identifying how changes at one level would impact others. This exercise can sharpen your ability to anticipate and reason through complex, multi-layered situations.

p.s If you think this sounds like you, Figma are hiring 3 PMs right now…

Until next time 👋

And that’s a wrap folks on one of the greatest software products of our generation. A product driving the UX/UI of most software products you use today.

Again, this wasn’t the usual analysis we do, and it was the first interview-based writeup we’ve done on How They Grow. If you want to get into the weeds of Figma’s product-led growth and their flywheels, this is the post to read.

Finally, a huge huge thank you to Kris for making the time to help with this piece. Absolute legend.

If you don’t use Figma yet, there’s really just one thing to do…(and don’t forget to explore Dev Mode!)

Otherwise, as always, thank you for reading! If you learned anything new today, you can sign up here for more issues. Also consider sharing this post, or perhaps becoming a paying subscriber to support my work.

Until next time.

— Jaryd ✌️

Amazing take and so cool to hear directly from Kris!

You are too kind 🙏 Thanks for the words about the piece!

Great one! Loved the "I am not a robot" example. Such a great way to explain abstraction.