🌱 5-Bit Fridays: Big mistakes made during discovery, The Strategy Kernel, raising prices, the core PLG KPI, and 90-day onboarding

#37

👋 Welcome to this week’s edition of 5-Bit Fridays. Your weekly roundup of 5 snackable—and actionable—insights from the best-in-tech, bringing you concrete advice on how to build and grow a product.

📬 To get future posts delivered to your inbox, drop your email here:

Happy Friday, friends 🍻

In case you missed it this week:

Google Analytics launched a new report to identify your most engaged and profitable audiences.

Meta has just open-sourced their text-to-music and text-to-sound AI models. These gen AI use cases haven’t had much attention yet, but with publically available models to use, that may start to change.

Uber, at last, sees the green and reports a profit. However, before you jump the gun, this chart really puts it into perspective: I.e, they have a long way to go…

With Bob Iger’s return as Disney CEO, and his frustrations with the actor and writer strikes, could his last iconic move be to sell Disney to Apple? 👀

And most importantly, Swifties caused a 2.3 magnitude earthquake in Seattle at Taylor’s recent concert. Epic.🤘

Okay, down to business.

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

Lesser-known mistakes PMs make during discovery

The Strategy Kernel: Good / Bad Strategy

Raising prices for your product: Should you do it? If so, how?

The essential product-led KPI

Make the first 90 days count

Small ask: If you learn something new today, consider ❤️’ing this post or giving it a share. I’d be incredibly grateful, as it helps more people like you discover my writing.

Let’s get to it.

(#1) Lesser-known mistakes PMs make during discovery

Before building anything, or even thinking about a solution to a problem, you need to understand what the problem is, who has it, and what job they’d be hiring your product for (JTBD).

As you know, that’s the discovery phase. Beware anyone who skips this.

However, not all discovery is equal. There are lots of pitfalls that lead to weaker findings and misguided actions based on shaky premises. When I was doing early research at my startup back in 2017, I for sure made tons of discovery mistakes as a first-time founder. Over time, I made fewer of them. And as I did, my hit rate from insight to successful product went up—bringing our customers features that they used, and continued to use.

Luckily for all of us, Aatir Abdul Rauf from Behind Product Lines recently put together an epic list of “lesser-known” mistakes PMs and founders make in this phase. It’s a goldmine of advice for anyone who speaks to customers in the context of research.

Here are some big oversights folks make during discovery, summarized.

Conducting discovery without building the culture to support it. It’s important to set up the right processes for discovery and have at least one person on the leadership team who buys into bottom-up ideas that come from your research.

Attempting discovery without a strategic vision. While research is a big input to strategy (as strategy/the roadmap is fluid based on new learnings), it’s important to go into discovery with a guiding strategic vision. Without a map of sorts, as Aatir says, you’ll likely:

ask questions that are all over the place

struggle to prioritize feedback received

fail to gather insights on what will deliver the highest impact for the product

Working on discovery reactively: Don’t just go run to learn from your users when something comes up. Proactive always trumps reactive, and your goal should be to have a culture of continuous discovery, always be learning, and automate feedback cycles (Read: The why and how of daily user touchpoints).

Talking to customers only: Speaking to existing customers is important, but it’s also easy—you have their email and they’re actively using your product. Because it’s easiest, folks often ignore talking to prospects and churned customers. Getting their attention can be harder, but it’s essential for a multi-dimensional view of the market. As Aatir puts it:

“Customers can only speak to the existing product and their current needs. Churned users, however, will spotlight the broken shards in your product that aren’t often talked about. High-fit prospects can share how they’re solving problems today and where alternatives perform well.”

Talking to EVERY kind of customer: Not all feedback is equal. It’s important to know which segments of users to listen to, and who to ignore. During discovery, focus largely on your Ideal Customer Profile/High Expectation Customer. Otherwise, the dispersion of ideas can be chaotic.

Failing to frame the problem correctly: If you ask poor questions, you’ll get poor answers, which end up a few weeks/months later as a feature/product with low adoption/engagement/retention. Perhaps an exaggeration, but good questions are really the bedrock of excellent products. As Aatir says, along with an awesome visual of his, “If you don’t get to the job to be done, you’ll frame the problem incorrectly and in turn, you’ll swim in the wrong solution space”.

Being over-sensitive to intriguing feedback. Oh boy, I’ve been a culprit of this. This is absolutely an easy one to fall into. You’re speaking to a customer, and suddenly they say something that strikes you as novel and super interesting. You get excited, thinking you’ve uncovered a game-changing gem of wisdom. You bring it to the team and just race into coming up with a solution. But, you let the buzz get ahead of you, and you may very well be building something for a very rare need. “It’s important to isolate emotion from the feedback received. Anecdotal feedback, although not irrelevant, needs to be taken with a grain of salt and cross-validated.” Be careful when you hear something seemingly huge that nobody else has mentioned before.

Limiting discovery to live interactions: Simply, discovery is not just about Zoom calls with customers. You need to think holistically about your full evidence ecosystem, like: Leadership, sales, customer success/support, marketing, analytics, macro trends, surveys’ community pages, and your own observations.

Not spending enough time distilling information: Talking to customers and gathering data is the easy part. It’s what you do with those findings that really matters. And it starts with consolidating and documenting your research appropriately, making it accessible to others, and then prioritizing themes based on your strategy and developing hypotheses and action plans to validate them.

Using discovery to market the solution: Don’t sell your product here and ask binary questions like, “Would you use this…”. Discovery is all about learning.

Using discovery to explore just function and not messaging. Talking to users is a great opportunity to hear how people describe their problems. That same verbiage can be used in further discovery endeavors, as well as feed nicely into product marketing. Remember, positioning isn’t how you describe your product—it’s how customers do.

For more of Aatir’s tactical advice on product building, be sure to subscribe to Behind Product Lines.

Go deeper: 🧠

(#2) The Strategy Kernel: Good / Bad Strategy

Professor Richard Rumelt, the author of Good Strategy Bad Strategy and several other books which together have formed an almost biblical library for business strategy enthusiasts, is truly the Grandstrategist of our generation in a class of his own.

There are a lot of definitions of what strategy is, but as he simply puts it: “Strategy is how you overcome the obstacles that stand between where you are and what you want to achieve”.

No fancy MBA definitions, just straight to the point. Which is largely what he says strategy should be. The more complex it is, and the more fluff around it, the less likely it is to lead to real business success.

I’ve been rereading his classic book, Good Strategy Bad Strategy, and thought I’d make a bit out of it today. If you’ve never read it and you’re involved in making/influencing strategic decisions, my advice is to go buy it right now—this is a very abbreviated tease of all his insights. And if you have read it, this little recap may serve as an important reminder.

Okay, so if the purpose of strategy is to offer an achievable way of overcoming a key challenge, what does a good strategy actually consist of?

The biggest takeaway from the book is that good strategy has three parts. It’s what Richard calls the kernel.

The Kernel of good strategy

Diagnosis 🔬

A diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge. A good diagnosis simplifies the often overwhelming complexity of reality by identifying certain aspects of the situation as critical.

The first step in setting your strategy is to assess a set of facts and then use that assessment to direct your effort to what is most important.

And all good assessments of a situation, whether that's within your market or company, start by answering the question, "What's going on?” This helps you solve the fundamental problem of comprehending the state of things.

At a minimum, a diagnosis names or classifies the situation, linking facts into patterns and suggesting that more attention be paid to some issues and less to others. In other words, it should replace the complexity of reality with a simple and memorable story, one that calls attention to its crucial aspects and allows you to focus your problem-solving.

The guiding policy and actions of a strategy (below) are then attempts to solve the diagnosed problem. When the diagnosis changes, so should your strategy.

Key question: Why are we doing this?

Guiding policy 🧭

A guiding policy for dealing with the challenge. This is an overall approach chosen to cope with or overcome the obstacles identified in the diagnosis.

With your diagnosed problem, your policy should point you in a specific direction but not list specific actions.

In the same way that the diagnosis helps to focus the problem, the guiding policy should help to focus on the solution. And importantly, a good guiding policy tackles the obstacles identified in the diagnosis by creating or drawing upon sources of advantage.

Key question: What is the plan?

Coherent actions 🗺️

A set of coherent actions that are designed to carry out the guiding policy. These are steps that are coordinated with one another to work together in accomplishing the guiding policy.

At best, Richard calls out that most "strategies" start and end here. But just listing actions fails to give any context behind them.

You can think of coherent actions as your company-level goals, OKRs, or rocks. From here, your roadmap will start to take shape.

Key question: How will we accomplish this strategy?

Let’s put it to practice with an example from the book:

Nvidia: A+ strategy

Nvidia, a designer of 3D-graphics chips, had a rapid rise to the top, passing apparently stronger firms, including Intel, along the way in the 3D-graphics market. Since Jen-Hsun Huang became CEO in 1999 the company's shares increased 21-fold, even beating Apple during that same period.

Diagnosis: recognizing that 3D-graphics chips were the future of computing (given the almost infinite demand for graphics improvement that came from PC gaming).

Guiding policy: the shift from a holistic multi-media approach to a sharp focus on improved graphics for PCs through the development of superior graphics processing units (GPUs).

Action points: 1) The establishment of three separate development teams; 2) reducing the chance of delays in production/design by investing heavily in specific design simulation processes; 3) reducing process delays involving the lack of control over driver production, by developing a unified driver architecture (UDA). All Nvidia chips would use the same downloadable driver software, making everything run more smoothly at all stages (for both Nvidia and its customers).

Nvidia grew at a rate of about 67% per year from 2001 to 2007 and circumnavigated the design and production bottlenecks faced by companies like Intel. Despite similar growth to Nvidia during that period, Intel had the effects of its performance increases dulled by process issues. Nvidia, meanwhile, won consumers over with more frequent top-tier GPUs.

Where competitors like Silicon Graphics spread themselves too thin, Nvidia's strategy during that time was intuitive, focused, and executed well.

Okay, and what about bad strategy?

Richard says bad strategy can usually be identified by its four horsemen: (1) fluff, (2) failure to face the challenge, (3) mistaking goals for strategy, and (3) bad strategic objectives.

According to him, most strategies are "bad." Not because the strategy is wrong but because it is not a strategy. Often what passes for strategy is really a goal or, at best, a tactic.

To help frame good vs bad, here’s a handy cheat sheet Kristian Sorensen put together.

And I’ll leave you with this clip of Richard talking about who succeeds in business, with a lovely recollection of his conversation with Steve Jobs shortly after his return to a failing Apple.

Go deeper: 🧠

(#3) Raising prices for your product: Should you do it? If so, how?

I’m sure you saw this recently if you opened Spotify…

What Spotify is doing is based on a simple premise: The quickest way to increase your revenue is to just charge more for your product.

With 210M premium subscribers, that little initiative (nobody is canceling their favorite music app because of an extra dollar) brings Spotify another $2.5 billion a year. Not bad.

This little example (although, many others do it all the time) is illustrative that price is one of the most powerful levers you have in your business. If you want to increase the value of your company in a sustainable way (i.e. not just by acquiring new customers), you need to increase revenue from existing customers (AKA, LTV), which happens when you either (1) get users to stick around longer, and/or (2) get users to pay more.

Dan Layfield (ex-PM at Uber and Codecademy) wrote a great piece looking at point 2: increasing prices.

Execution-wise, price bumps need to be tested (which we’ll get to). But first, what’s the more nuanced view of the impact of price changes?

Price raises are tricky because they have: knowable positive impacts, unknowable positive impacts, knowable negative impacts, & unknowable negative impacts.

Some of these will show up within the measurement window of an A/B test, others won’t.

You can’t say exactly what is going to happen, but assuming that you run a successful pricing test, you should be able to anticipate a range of impacts:

Potential Positive impacts:

Increase the LTV of your user base, which will allow you to spend more to acquire users.

This opens up new acquisition channels, fueling additional user growth.

Likely attracting a higher “quality” user, who is more committed to your product, this might lower associated support costs as these users if those are material.

Raise the enterprise value of your company, which allows you to raise more money if you need it and/or attract a higher talent level of employee.

Potential Negative Impacts:

Throw off your existing LTV calculations, as mentioned in the post above.

By definition, you’ll have to see users at this new price point reach the end of their lifecycle. This, in turn, might throw off your CAC to LTV spending ratio in paid media.

It changes where your brand sits in the mind of a consumer, which might need to initiate more branding work. This will only happen if you go from the lowest price to medium or medium to the highest.

Unlikely to matter if you are adding a dollar to your price as Spotify did.

Potentially turn slow down word of mouth and brand growth. If you raise your prices successfully, you will likely have a smaller group of users paying you more.

This slightly smaller user base means that there are fewer people to tell other people about your product, which slows down word of mouth.

Users are also way more likely to talk about a product they see as a great tradeoff between what they pay and the value they receive.

And with that in mind…

4-steps to test price changes

Scrub any mention of pricing from as many pages as you can.

The more places you mention your price (i.e. blog posts, emails, the odd landing page), the more areas you need to consider when A/B testing the announcement of a new price. By keeping pricing details on a pricing page, it becomes much easier to set up tests.

Set up & run an A/B test

When experimenting with a new price, it’s best to test on cohorts of new users. And between your control and treatment, the main thing you want to watch is revenue per user—not, say, total checkouts/conversions. If fewer people join, but you make more money, that’s a win.

Also, Dan points out you need to measure churn, and if applicable, plan ratios (monthly, annual).

Now, you might be wondering what price point to set. In Spotify’s case, as it is with more digital goods with no cost of production, prices are driven by the perceived value of the product in the market. At the core, the idea is straightforward: the higher your price, the lower your demand will be. However, if the price is too low, you won’t make a lot of money even though you might sell a lot. Similarly, if the price is too high, you won’t make a lot of money even though each unit sold brings you more cash. This is Economics 101: the principle of price elasticity of demand.

If you did any Ecos classes, you’ll know graphs like that have an equilibrium. AKA, every product has a price point at which revenues become maximum. If you price it higher, the revenues will fall. If you price it lower, the revenues will fall. You can’t just sit and draw your price-demand curve unfortunately, you need to use testing to find it.

Communicate results widely in the company

Once you’ve done your test, you need to ensure everyone understands the value created and you have the executive buy-in on the results. Also, in case it’s not clear, you definitely need senior buy-in before testing something like this.

Announce your price raise to users

With your decision to raise prices locked in, next, you need to let your market know. The best way to announce this is to relate your price bump to increased product value.

From here, be clear about who’s impacted, and when.

(#4) The essential product-led KPI

Yesterday, Kyle Poyar shared a valuable piece of advice on LI. (Follow him for more)

Hot take: Activated sign-ups are >>> than total sign-ups as a PLG KPI.

Many companies have poured resources into conversion optimization as a way to generate as many sign-ups as possible.

In many cases these companies celebrate their acceleration in sign-up growth only to realize later that the extra sign-ups never translated into more customers or revenue.

If this sounds like you, ditch sign-ups as a KPI in favor of activated sign-ups. Here's why:

💰 Activated sign-ups are far more predictive of the future outcomes you care about (revenue, conversion, etc.) than sign-ups alone.

A sign-up could be a bot, a student, a competitor, a tire-kicker, a VC (guilty 😊) OR someone with serious intent. Looking at activation helps to screen out the noise from the signal.

🤝 Activated sign-ups create much closer alignment between Marketing <> Product <> Growth <> Sales.

Instead of marketing's job stopping at the sign-up form, marketing now has to get much more embedded into product interactions and whether a user fits their ICP. Tracking activated sign-ups leads to better conversations and collaboration across teams.

⏲️ Activated sign-ups happen fast, which allows you to experiment quickly.

In a PLG business, it can take a long time before a user converts to a paying customer or generates a significant ACV. If you wait the 3 or 6 or 9+ months for that to happen, you can't get a quick read on whether to double down on a new channel or whether your test had the desired impact. But activation happens quickly - generally in 1-2 days after sign-up - and won't slow you down.

And in the context of driving activation at product-led orgs, probably the best way to do that is through excellent onboarding.

And traditionally, onboarding is viewed in two ways—either “Let’s point out our interface” or “Let’s decide where we want our users to end up and push them that way.”

Both play important roles in an onboarding experience, but if not implemented in combination with other approaches, in isolation, they could miss the mark because they don’t understand the difference between correlation and causation. AKA—just because someone has finished your onboarding steps or they’ve been told how to add a teammate, certainly doesn’t mean they’ll discover your product’s value, engage a lot, and ultimately retain.

The kernel of onboarding…a truly magical first mile…is a UX that pays less attention to getting folks to complete steps the business cares about and more about getting them to experience aha moments. At the end of the day, customers reaching value and forming habits around those value points is what drives long-term value. And these successful moments very rarely have nothing to do with optimizing button colors or calls to action and everything to do with gaining a better understanding of who your user is, what it is they are trying to achieve, and where they currently are in your workflow.

If you have some time and want to go pull on this thread some more, Intercom (Read: How Intercom Grows) has created an epic 100-page ebook on this. I’m still making my way through it, but it’s top-shelf stuff. 👇

(#5) Make the first 90 days count

Joining a new team is challenging. You go from company expert to the newbie who needs to learn and figure things out. Throw working remotely into the mix, and you have another element to add to the difficulties of getting fully up to speed.

That’s why early onboarding is so important.

Some companies/teams have that fleshed out and nail the first 7,30,60, and 90-day onboarding journey of new hires. Others either haven’t got there yet or have one but it sucks.

That’s why you want to have your own plan at the ready. Plus, doing it yourself gives you your own personal roadmap for getting yourself in a position to meaningfully contribute ASAP. You know what you do/don’t know better than anyone else.

In a great post, Deb Liu wrote about the onboarding plan she created for herself after leaving Facebook and joining Ancestry as their CEO. As she put it, writing and sharing this plan with your manager/team creates transparency of information and ensures your team understands:

Your priorities

Your timeframe

Your commitments and deliverables

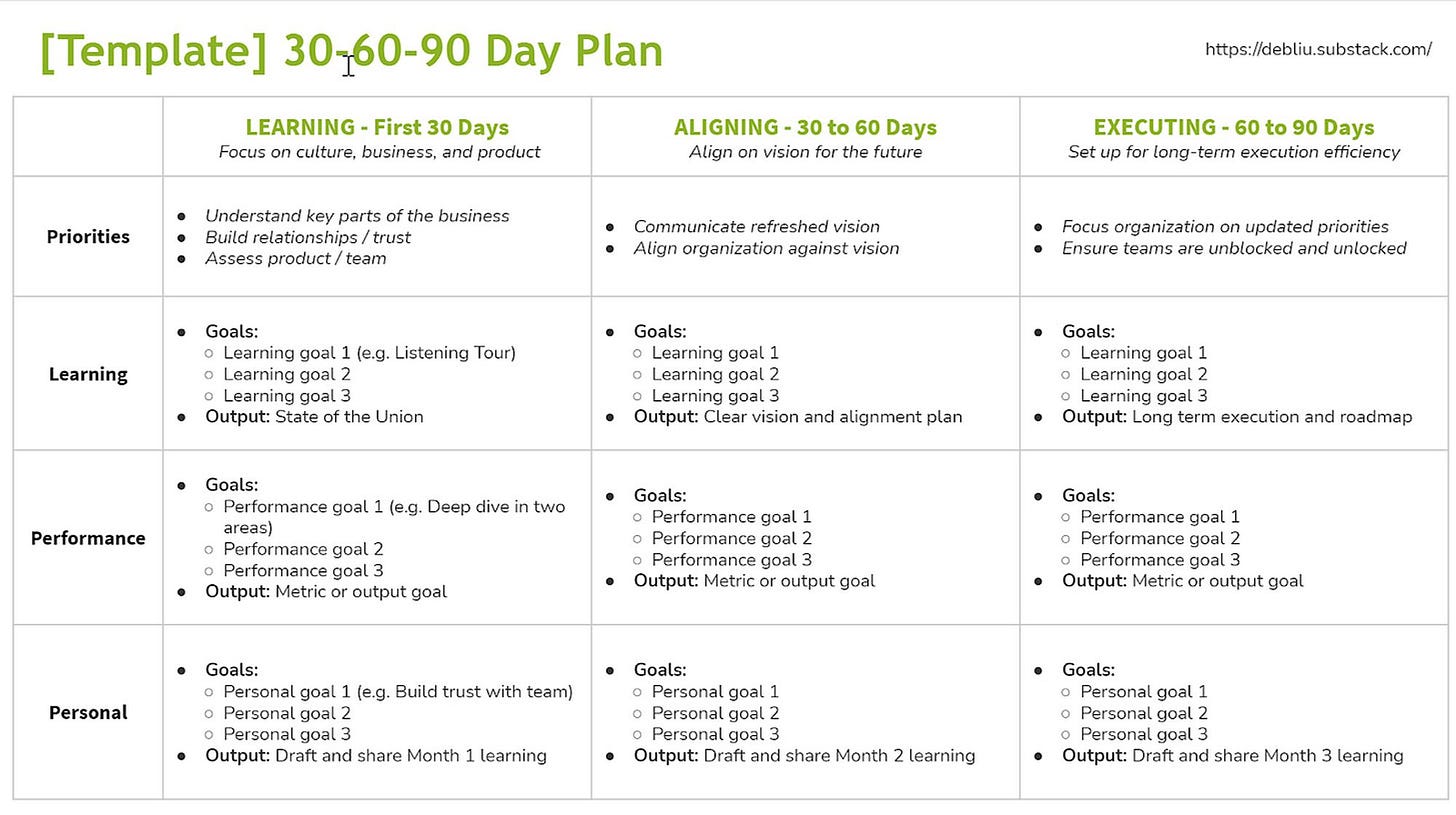

It shouldn’t be complicated, but it does need to be clear and easy to understand at a glance. Below is Deb’s simple template she made, inspired by the Muse’s onboarding plan.

She also outlines some simple steps to help you build a clear action plan.

Start with the end of the first 90 days in mind. It is easy to start a new role and hope to learn on the job, but without a clear idea of what you want to accomplish, you won’t be able to make the most of the time you have at the start. Like it or not, you are on an invisible clock that starts ticking the minute you walk in the door. You get to enjoy a honeymoon period, but within three months, any problems and opportunities become yours. During this starting period, you have the chance to ask questions and ramp up on the organization, business, and company culture without judgment, so make the most of it. The end of the first 90 days marks when you will be expected to have a strong understanding of the team, culture, and business.

Have clear priorities for each month. Mapping out themes aligned to your priorities makes it much easier for others to help you as you onboard. I chose Learning, Aligning, and Executing as my themes after examining the needs of the Ancestry organization. These work well if you are taking on a new role during peacetime, when you will have a chance to onboard and make sure everyone understands your goals. Joining a team or company during wartime may require you to adapt these themes into something that gets you into the action faster.

Communicate your plan. Sharing your 30-60-90 Day Plan themes and priorities ensures that everyone is on the same page. I shared an early detailed draft of my plan with the Ancestry Senior Leadership Team and solicited their input. I then published a high-level summary to the entire company so that everyone knows what I am working on.

Make clear commitments and deliver. Trust is the most important thing to build as you onboard to a new role. The best way to build trust is to make a commitment and live up to it. People watch your “say”/”do” ratio. Holding yourself accountable means setting clear goals and sharing your progress against them. They are also looking to see when you have learned something new and pivoting to accommodate new information. By publishing your priorities and sharing the output, people you work with will know what to expect and know when you have crossed the finish line.

But what if you’re joining a team as the first product manager? Fear not, Lenny wrote a great piece on that.

🌱 And now, byte on this if you have time 🧠

Given all the hype with Barbenheimmer—I haven’t seen either yet 🙉—I thought this recent video by Kurzgesagt (my favorite YouTube channel that creates incredible animation videos explaining things with optimistic nihilism) is timely: The Most Dangerous Weapon Is Not Nuclear.

Give it a watch (11m).

And that’s a wrap, folks. 🫡

If you learned something new, or just enjoyed the read, the best way to support this newsletter is to give this post a like, share, or a restack. It helps other folks on Substack discover my writing.

Or, if you’re a writer on Substack, enjoy my work, and think your own audience would find value in my various series (How They Grow, Why They Died, 5-Bit Fridays, The HTG Show), I’d love it if you would consider adding HTG to your recommendations.

Until next time.

— Jaryd✌️

A solid CS team to deliver the price increase goes a long way too

Thanks for the shout out, Jaryd.