🌱 5-Bit Fridays: The 3 pillars of every great marketing strategy, when to invest in growth, product > strategy > biz model, executive engagement, and how half staffed is unstaffed

#36

👋 Welcome to this week’s edition of 5-Bit Fridays. Your weekly roundup of 5 snackable—and actionable—insights from the best-in-tech, bringing you concrete advice on how to build and grow a product.

Happy Friday, friends 🍻

In case you missed it this week, here’s some news for ya.

Zuck’s big Year of Efficiency is paying off, with Meta’s Q2 earnings raking in a nice $32B—their most profitable quarter since 2021.

Speaking of earnings week…Snap is probably screwed again. Elon, leave them alone.

Speaking of Elon, analysts say Twitter’s X rebrand wiped out $4-20B in value. I’d say the person responsible would be fired, except you know whodunnit. Also, Twitter just took the @x handle without warning or compensating the original owner. Sorry bro, you’ve been Eloned.

And most interesting this week, Fiat’s new tiny car comes equipped with a shower. Looks like a $3.5K/m studio apartment in Manhattan to me.

Anyway, enough messing around.

Here’s what we’ve got this week:

Product > Strategy > Business Model

The 3 pillars of every great marketing strategy: Information Wars, Air Wars, and Ground Wars

When to invest in growth, and the ideal growth PM candidate

Half staffed is unstaffed

Executive engagement

Small ask: If you learn something new today, consider ❤️’ing this post or giving it a share. I’d be incredibly grateful, as it helps more people like you discover my writing.

Let’s get to it.

(#1) Product > Strategy > Business Model

Just earlier this week I came across Fred Wilson’s writing for the first time. Fred has been a VC since 1986, founded Union Square Ventures, and luckily for us, regularly blogs about his insights.

Across his career leading investments in companies like Twitter, Tumblr, Kickstarter, Etsy, Foursquare, and many others, Fred has time and time again seen entrepreneurs making what he sees as a huge, costly, and painful to fix mistake: spending too much time on the business model before locking down strategy—or worse— over-indexing on strategy and business model before having the product right first.

And “getting the product right”, of course, means finding product market fit—not simply just having a product built/launched.

Fred’s hard-won experience has led to him believe that moving to a business model before finding product market fit can be the worst thing for your product. Time and again, he’s seen revenue models that just were not aligned with the company’s strategic direction. So, his advice is not to rush into spending too much time figuring out the business model without first finding PMF, then taking the time to develop a crisp, clear, and smart strategy for your product. And then, from there, your business model will just come naturally. To illustrate, here’s how he recalls his Twitter experience:

I remember back to the 2009 time period at Twitter. The service had most certainly found product market fit. And the team turned its attention to business model. There were all sorts of discussions of paid accounts, subscriptions, a data business, and many more ideas. At the same time, Ev Williams was articulating a strategy that had Twitter becoming the "an information network that people use to discover what they care about." And so the strategy required getting as many sources of information on to Twitter and as many users accessing it. It was all about network size. That strategy required a business model that kept the service free for everyone and open to all comers. That led to the promoted suite business model. Twitter executed product > strategy > business model very well.

Now, I appreciate this advice of Product > Strategy > Business Model for sure, and really like the hierarchy/order-of-operations that Fred presents us here: product-market fit needs to exist for the rest to even matter. But, I believe even before having PMF, you do need to have a plan for how you will make money. And I bring that up because I just want to be crystal clear that ignoring strategy and business model because you’re just focused on PMF can lead you down a bad path too.

As I was mulling over Fred’s advice, my mind jumped to another approach that resonates with me more—Brian Balfour’s four-fit model, which we spoke about earlier this year. Simply, Brian argues that product market fit isn’t enough.

It’s not just (1) great product, (2) product/market fit, or (3) growth hacking that sets apart the average from the great. Rather, the difference between the $100M+ companies, and those that struggle are the ones that are able to make four pieces in a puzzle fit:

As his model shows, there are four essential fits: Market Product Fit, Product Channel Fit, Channel Model Fit, and Model Market Fit. He adds:

There are three extremely important points I want to hammer home:

You need to find four fits to grow to $100M+ company in a venture-backed time frame.

Each of these fits influence each other, so you can’t think about them in isolation.

The fits are always evolving/changing/breaking. When that happens, you can’t simply change one element, you have to revisit and potentially change them all.

He expands on each fit across a series of posts…let me summarize for you:

The central idea here is the market should always be thought about first. People often build a solution in search of a problem, whereas it’s the problem and market definition that need to always come first. You can’t screw with a hammer.

Products are built to fit with channels. Channels do not mold to products. Simply, this is because you don’t get to define the rules of the channel — “the channel defines the rule of the channel.” PCF is when your product is designed to work well with a specific distribution channel, meaning you can’t think about product and channel as silos. Takeaway? It’s better to prioritize and tackle one or two at a time in pursuit of your power channel. Here is a step-by-step on how to test and prioritize your growth channels

Simply, your business model should determine your channels. Depending on (1) how much money you make from customers and (2) how much it costs you to acquire them — that will be pretty prescriptive of what channels make sense. So, you can't think about your model and your channel in silos. If you’re making changes to your model (pricing, how you charge, etc.), you also need to revisit your channel to make sure you still have CMF.

Market dynamics need to determine your business model. Factors like how many total customers there are, the propensity to pay, buying process, etc. will all impact how you charge for your product. If you have 500 companies total, $100 bucks a month isn’t going to cut it. The back of the napkin math here is: $price x #customers x % You Think You Can Capture = $100M/year revenue

So, as a closing thought here, yes—yes product-market fit matters the most, but part of achieving that is you’re able to acquire customers that are willing to pay you. And that means 4-fits are really what matters.

(#2) The 3 pillars of every great marketing strategy: Information Wars, Air Wars, and Ground Wars

Something great happened this week. While perusing Substack’s Discover tab, I found Category Pirates 🏴☠️ : a newsletter all about category design and category creation.

Honestly, it’s wonderful. And just to try to show how interested I was in what they had to say, I became a paid subscriber after stumbling on a free post of theirs, before even finishing reading it. I’ve never done that before.

Anyway, I was reading a lengthy post of theirs (like my deep dives) about category creation, and there was one insight I really wanted to share with you today. It’s about creating a legendary marketing strategy, which the authors call The Lightning Strike Strategy.

As they wrote:

Every startup, company, and creator is fighting 3 different types of wars at the same time: the war for who frames the problem, names and claims the solution, and as a result owns the narrative (The Information Wars); the war for who is then able to most effectively “sell” that narrative at scale (The Air Wars); and the war for who can best convert new recruits to the war effort—prospect to prospect, customer to customer, consumer to consumer, and thus make the cash register sing. (The Ground Wars).

To give you a bit more context, here’s a quick summary of each of these wars:

Information Wars: This is what sets your strategic context. It’s a mix of all the ways that you educate your target customers (and customers) about the category you’re designing. Significantly, it’s also about learning from your Superconsumers to accelerate your effectiveness both in the air and on the ground. This is very much focused on POV marketing than anything else.

Air Wars: In many ways, marketing is “sales at scale.” Air Wars are the high-level strategic marketing you do in service of this new category you are creating, all the while positioning yourself as the leader within it. Simply. it’s taking your information pack and using that for demand generation.

Ground Wars: Getting more granular, think of this as your marketing tactics that support your strategic efforts in marketing the category and driving near-term revenue. These efforts are more focused on demand capture.

As the authors call out, most companies and marketing teams focus on the ground wars. In typical annual planning cycles, debating the premise and context of the business isn’t exactly an agenda item. When making future-looking marketing plans, they note that teams often start with last year’s marketing plan and metrics as the template. But, like basing your future on what you felt 2 years ago…this leads to continuing the past, not creating a different future adjusted for new context.

So, an excellent marketing plan needs to mix all three types of wars together. As the pirates describe:

When a company over-rotates and disproportionately spends more marketing dollars and people hours in any one of these areas, they usually run into a problem. Either they spend too much time and money or both trying to “sell at scale” (Air Wars), not realizing they don’t have boots on the ground (Ground Wars) to effectively convert those prospects into customers. Or they become too myopic and focused on winning each individual battle (Ground Wars) that they forget what cause they’re fighting for in the first place (Information War).

To go deeper, continue reading Lighting Strike Market Strategy

(#3) When to invest in growth, and the ideal growth PM candidate

A great way to burn cash money, waste your resources, and jeopardize the future of your company is to invest too much into a growth program before you've proven you can retain customers.

Don’t believe me? Forget not the lessons of old Quibi.

In short, don’t go and built a growth team (at least, one focused on acquisition) to invest big bucks behind until you know for sure you don’t have the proverbial leaky bucket problem.

As an aside: you can definitely invest in a retention growth team if that’s the issue you have.

Okay, so how do you, practically, know when to start investing in growth?

First, check your retention

Select the right metrics, not vanity metrics (like app downloads). Choose a leading indicator of revenue and repeat the behavior.

For marketplace businesses, create metrics for both supply and demand sides.

Examples of demand side metrics include "Rebook rate" and "Nights booked per user."

Examples of supply-side metrics include "Active hosts" and "Bookings per active host."

Choose an appropriate period for your cohort (e.g., daily, weekly, or monthly) based on the nature of your business.

For Airbnb, the focus is on annual retention due to the infrequency of travel.

For Uber, the focus is on monthly and weekly retention due to frequent usage.

Identify an initial user action within the first period (AKA, your aha moment).

For Airbnb, the initial action is booking a room for at least one night.

For Uber, the initial action is either a first ride or a first drive.

Identify a subsequent user action in the second period.

Calculate the percentage of the user base still engaging in that action in the second period (AKA, how often are people hitting your core value)

For Airbnb, this is the percentage of users who rebook each year.

For Uber, this is the percentage of riders who use Uber every month.

Then, figure out if it’s good or not

To determine if your retention is good, Anu Hariharan from YC suggests you go through these 3 steps:

1. Stable long-term retention: Long-term retention should be stable and parallel to the x-axis (the y-axis represents the retention metric). It is common to see a dip after the first period (e.g., month 2 for high-velocity products or year 2 for low-velocity products), but the most important thing is to make sure that the long-term retention is stable and parallel to the x-axis (see this in the Cohort Analysis graph below).

2. Long-term retention in line with "average or median" benchmarks in your specific vertical: It is important to benchmark your retention against companies in your specific vertical. For example, stable long-term retention of 10% is poor if you are a social network.

3. Newer cohorts should perform better: "Cohort" refers to the group of new customers that started using your service that particular month. Determine whether newer cohorts are performing progressively better than older cohorts. If the retention of newer cohorts are better than older cohorts, it implies that you are improving your product and value proposition.

And to gauge how good yours is, or not, it’s worth benchmarking your retention against companies in your specific vertical. Sounds like a pain in the arse to do. Luckily, Lenny did it for us. 👇

Learn more: 🧠

Once you've passed these checks and know that you have good retention, you can take the first steps to build your formal growth team. 👇

Growth teams, and what an ideal growth PM candidate looks like

In the early days at a company, pretty much everyone is responsible for growth as they are solidifying product market fit, and some companies treat this as a shared responsibility even past product market fit. The reason a company forms a dedicated growth team is to pour gasoline into product market fit by launching structured experiments to drive a desired behavior/action.If you have proven sustainable retention, you can focus on building a dedicated team to improve retention even further while acquiring and activating and retaining incremental new users.

Here's the most common makeup of an initial, Year 1 Growth Team:

Year 1 Growth Team = 1 Growth-focused PM + 2-3 Growth Engineers + 1-2 Growth Data Scientists

— Anu Hariharan, How to Set Up, Hire and Scale a Growth Strategy and Team

From that equation, let’s just focus on what to look for when hiring a growth PM. YC calls out 4 traits to specifically look for:

Data-oriented: Ideal candidates need to be data-focused and curious, always asking "Why?" even if growth is positive. The riskiest times are when numbers drop or increase without clear reasons.

Prior Growth Experience: Ideally, the PM has prior experience in growth-focused competitive industries like e-commerce or apps. This rules out recruiting from companies like Google or Apple, which didn't scale through competitive growth strategies.

Former Startup Founder (bonus): Former founders make great PMs due to their independent thinking, risk-taking, and perseverance. This is important as many experiments will fail.

Existing PM (bonus): If an existing PM possesses these characteristics, they could become the Growth PM. Their established relationships within the company can speed up the team's progress. However, this isn't a necessity, as some companies hire specifically for this role.

(#4) Half staffed is unstaffed

It is a pretty exciting time for technologists. There is no shortage of good ideas to go work on. We are kids in a technological candy shop. It sounds like an enviable position.

Unfortunately, having too many good ideas at a company is almost as perilous a position as having too few. It creates a form of the Tragedy of the Commons where every investment seems reasonable when evaluated on its own, but nonetheless yields an ineffective overall investment. Years ago an executive at Yahoo wrote the Peanut Butter Manifesto which detailed the consequences of spreading investment too thin.

— Andrew Bos (Boz), CTO at Meta

Expanding on that thought, Boz wrote a punchy article about the importance of prioritization in a world where ideas are plenty. Here are 5 key takeaways:

Avoid 'Idea Overload': Having too many ideas can lead to ineffective investment, similar to having too few. It's essential to focus not just on good ideas, but on the best ones. Always question whether there's something better. “As painful as ruthless prioritization is, it is not as painful as failing to do it.”

Use Inside-Out Staffing: At the organizational level, it's best to staff from the inside out. Fund the core operations fully first, then allocate remaining resources to other fully-funded teams one at a time, aligned with your goals. Stop when you can't fully staff another team.

Plan for Future Growth: Consider future team growth when allocating resources. If you can't afford to support successful teams' growth, you risk starving successful projects. The criteria for winding down a project should not be that it's failing, but that its success is being outpaced by other opportunities' potential. This requires discipline to shut down well-performing efforts that aren't the most important. A hard thing to do, for sure.

Optimize Personal Time: If you can't commit significant time to a project, it's often better not to work on it at all. Working on too many projects doesn't slow progress proportionately; it slows it more due to the mental energy required to switch between them.

Prioritize Ruthlessly: Prioritizing ruthlessly aligns everyone's efforts on a smaller number of crucial ideas, creating a more effective and collaborative way of building things.

For more of Boz’s thoughts, check out his writing here.

(#5) Executive engagement

In a great essay by Marty Cagan and Jon Moore, they drive home an important point: senior leads (AKA, founders, CEOs, etc) need to empower teams in the product development process by shifting from a command-and-control leadership model to one that prioritizes autonomy and communication.

But, as Marty and Jon say, “Changing to an empowered product-team model represents a major cultural and behavioral change, and much of this change necessarily needs to start at the very top. Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as saying “just back off and give the people space to do their work.” There are very real needs that senior leaders have in order to responsibly and effectively run the company. And in order to push decisions down to product teams, those teams need to understand the strategic context, much of which needs to come from the senior leaders. So there’s no question that we need frequent high-quality engagement. It’s just the nature of the interactions that we’re talking about here”

Fortunately, they outline a set of interaction principles for great collaboration between senior leaders and product teams. Here are the takeaways:👇

Lead with Context, Not Control: Rather than imposing decisions, senior leaders should provide strategic context to empower their teams to make informed decisions. This includes sharing information about vision, strategy, financials, regulatory developments, industry trends, and partnerships.

Focus on Outcomes, Not Output: It's important to hold teams accountable for outcomes (i.e., the end results of their work) rather than output (the quantity of work produced). Teams should be given the space to figure out their own solutions, vs overprescription of what to do.

Accept Uncertainty: It’s important for everyone – but especially senior leadership – to understand that with tech products, there are many things that we simply can’t know in advance. Knowing what you can’t know, and admitting what you don’t know, is essential for strong product organizations.

Data Over Opinions: Using data can provide objective evidence to support decisions, and pulling up results from a test is a reliable way to settle differences in opinions.

High-Integrity Commitments: There will be times when specific deadlines just must be met. However, these types of commitments should be made very sparingly, with a recognition that the process of making a high-integrity commitment requires time and effort.

Maintain Focus: It's essential to maintain a laser focus on the company’s key objectives, which (to Boz’s point) may require turning down other opportunities and knowing how to prioritize ruthlessly.

Cultivate Missionaries, Not Mercenaries: For effective teams, competency, inspiration from strategic context, and trust are crucial. It’s key to give teams space to do their own work to demonstrate they have ownership and responsibility.

Prioritize Transparency: Sharing the reasons behind decisions, including both successes and failures, is key to creating a culture of trust and openness.

You Are Not the Customer: In any organization, there will be many people that have strong opinions, but strong product organizations need to concentrate on coming up with solutions that our users and customers love, yet work for the business. Many people will think they are representing the customer, and that is an especially dangerous trap for founders, product managers, designers, and sales and services staff, but there is no substitute for going to the true users and customers.

Fix the Team First: When problems arise, first ensure that the team is correctly composed and equipped to handle them. This may involve coaching or staffing changes.

Empower Engineers: Engineers should be given the chance to contribute to product discovery and decision-making, rather than just implementing features designed by others.

Distinguish Between Ideas and Directives: Senior leaders should make it clear when they are offering ideas for consideration and when they are issuing directives that need to be followed.

Prototype vs. Product: When we are communicating about product with senior executives, we need to be very clear whether we are talking about something that is being explored in product discovery (prototypes), or whether we are discussing something that is now live and in production and visible to customers (products). Confusing the two can be very dangerous.

Minimize Surprises: One of the worst forms of waste is when a product team builds a product quality, scalable implementation of some capability, and then finds out afterward that there is some reason why this is not an acceptable or viable solution. So, ensure sensitive are identified and discussed before a product is built to prevent wasteful rework.

No Silver Bullets: Be aware that no single method or technique can guarantee success in product development. The hard work of product development can’t be bypassed or simplified with one-size-fits-all solutions. Context matters a ton.

Question to send you into the weekend: How does your team stack up? 🤔

🌱 And now, byte on this if you have time 🧠

As I said, I thoroughly enjoyed making my way through the archives of Category Pirates. On that note, here’s a post of theirs you might enjoy.

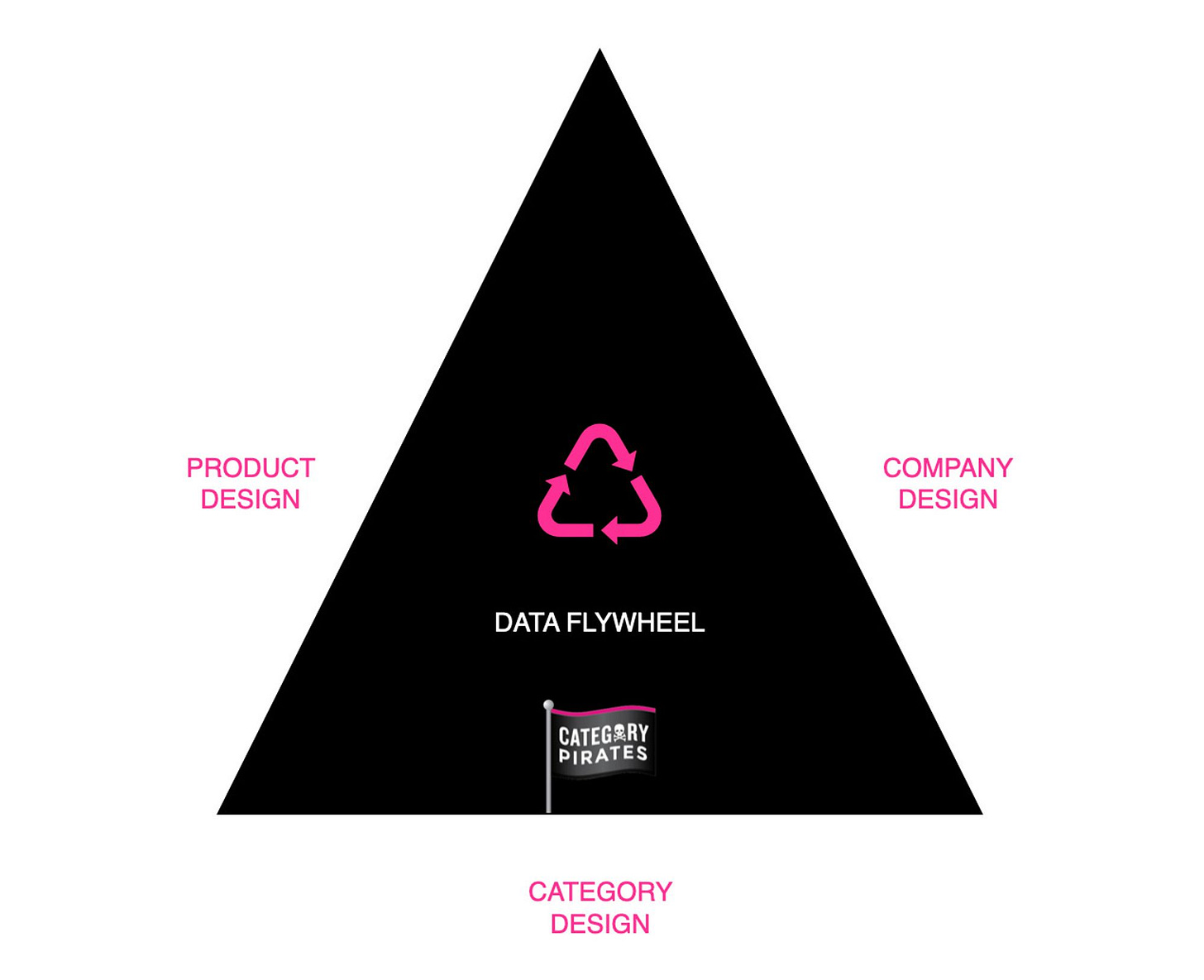

The Magic Triangle is the combination of product design, company design, and category design—each side with equal importance, ideally executed at the same time.

Product Design: The purposeful building of a product and experience that solves the problem the category needs solved. The goal here is what the business world traditionally calls “product-market fit”—which we see as strategically flawed thinking. What you really want is “product/category fit” (which we’ll clarify later in this letter).

Company Design: The purposeful creation of a business model and an organization with a culture and point of view that fits with the new category. The goal here is company/category fit, meaning you have engineered the right business model and missionary team for the problem you are looking to solve.

Category Design: The mindful creation and development of a new market category, designed so the category will pull in customers who will then make the company its Queen. In marketing terms, this is about winning over popular opinion, and teaching the world to abandon the old and embrace the new.

Read: The Magic Triangle: Why Category Design Is The Single Point Of Failure

And that’s a wrap, folks. 🫡

If you learned something new, or just enjoyed the read, the best way to support this newsletter is to give this post a like, share, or a restack. It helps other folks on Substack discover my writing.

Or, if you’re a writer on Substack, enjoy my work, and think your own audience would find value in my various series (How They Grow, Why They Died, 5-Bit Fridays, The HTG Show), I’d love it if you would consider adding HTG to your recommendations.

Until next time.

— Jaryd✌️

This was very insightful!